Honest Dissent(Synthesis Essay).doc

advertisement

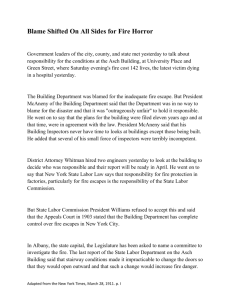

Anthony Greenwood Synthesis Essay (Obedience) English 2010, Prof. Combs, Sec. 28 Honest Dissent You cannot obey everything all the time. In fact, obeying one principle often requires disobeying another. Whenever there is a contradiction between what to obey, an act of obedience is simultaneously an act of disobedience. Through the initial idea of hypnosis, dating back to physician Charcot, a teacher of Sigmund Freud, and it's development into a more subtle theory of suggestibility, we arrive at a juncture where we question the validity of our own individual integrity and it pertains to our personal morals. Fromm argues with my support that it has been in the interest of the elite throughout history to frame obedience as a virtue, and disobedience as sin. One naturally finds themself asking, why obey anything at all? Milgrams frames it like this, “The essence of obedience is that a person comes to view himself as the instrument for carrying out another person's wishes, and he therefore no longer regards himself as responsible for his actions.” He persists “The most far-reaching consequence is that the person feels responsible to the authority directing him but feels no responsibility for the content of the actions that the authority prescribes.” This robotic obedience he recognizes would leave us a mass of helpless drones, an enslaved hivemind, ready to do evil, if it applied to all of us. In a striking act of hypocricy, many of the subjects in Milgrams experiment “protested even while they obeyed.” The ordinary people, recruited for the experiment, betrayed their own comfort, rather than to disobey a present authority figure. What confounds me is, this authority had very little in terms of actual power over the subject. None of the real world forms of coercion such as violence, punishment, or loss of privelege were present. Neither were other forms of persuasion such as substantial reward, or other promises. I gather from this, surprisingly, that people have an innate desire to please a perceived present authority over harming, even possibly killing, a not so present victim. If we assume the subjects in this experiment were acting rationally, we must conclude that the benefit of the satisfaction of pleasing the perceived present authority, outweighed the risk of harming a nonpresent victim. Although I am sure other influences factored into their decisions, including the contribution to science their participation made, and their assurance the Experimenter was responsible for the student, or victim. Readily apparent in Milgram's post-experiment paper, in a dialogue between the subject Prozi in the position of teacher and the Experimenter as the authority, people need to feel that the responsibility for the consequences of their actions rests on a superiors shoulders, before they are submissive to the order. This opens a glaring hole in our moral fail-safes, concerning what we are willing to do to another human being. As Milgram goes on to state in his paper “This is, perhaps, the most fundamental lesson of our study: ordinary people, simply doing their jobs, and without any particular hostility on their part, can become agents in a terrible destructive process.”(Milgram) When Milgrams study was altered to put a bureaucratic step between the subject and the actual flipping of the shock switches, people became much more submissive. Milgram concludes, “it is easy to ignore responsibility when one is only an intermediate link in a chain of actions” and I agree with his extrapotion. It is a continuance of the trend we have seen of shirking responsibility away from ourselves, to justify our participation in something we would otherwise denounce. With the increasing tendency of our sociological structure to promote specialization and narrow, rather than broad, involvement in the policy and decision making process, comes an increased risk that the chain of deferred responsibility may be abused, intentionally or not, to violate the moral and ethical codes we otherwise share as a larger whole. Many opponents of Milgrams work complain of the ethical treatment of the subjects, asserting that the psychological and physiological stress they underwent during the experiment was unethical and cruel. I sympathize with these claims, and find it ironic that before uncovering humans tendency to follow orders without fully evaluating the ethical consequences of their actions, the assistants in this test were a displaying the proposed truth of it. Parker cites one of the participants, anonymously filling out a questionnaire from Milgram, who wrote “ Since taking part in the experiment, I have suffered a mild heart attack. The one thing my doctor tells me that I must avoid is any form of tension.” And another turn of irony, another anonymous response obediently asks “Right now I'm in group therapy. Would it be OK if I showed this report to [the] group and the doctors at the clinic?” (Parker 715) Other detractors to Milgrams conclusions propose faults in the way the trials were run. That on a “concious or semi-concsious level” some of the subjects knew that they were being deceived, but played along anyways (Parker 716). This happenstance would certainly skew the reliability of the procedure. Though many of the subjects reported being “fully duped” such as participant Herbert Winer (717). It's my assertion that people are greatly varied in the disposition to conform. Asch's findings support this. Early studies which inspired Asch's Social Pressure experiment showed people's common trend of altering their judgements to better align with the majorities, or that of professional authorities. In his experiments, some subjects consistently answer correctly, against the grain of the group. And others betray or doubt their own senses and bend to the will of the group. Although factors, such as having another person dissent from the group preference encourages most subjects to be true to what they believe is correct. Although the independent choosers did not display “staunch confidence” Asch observes, “The most significant fact about them was not absence of responsiveness to the majority but a capacity to recover from doubt and to reestablish their equilibrium (4).” On the frightening side, perhaps, is the discovery that the “extremely yielding persons” began to believe that their differences from the majority reflected a “general deficiency in themselves, which at all costs they must hide (Asch 4).” But when the dissenter variable was introduced to Asch's test, I found it interesting that the more “flagrantly different” the choice of the dissenter, the more comfotable it made the subject to make his own choice. This is a testament to Fromm's claim that disobedience is a virtue, with which I enthusiastically agree. Lending more support to the beneficial nature of making decisions in accordance with what you believe to be the truth is the fact that, when given a partner who answered correctly, the subject in the Asch experiment was also more likely to answer correctly. But that is not the most significant reason to be true to yourself. When, after six trials the partner rejoined the erroneous majority, the subject was just as likely to conform after the desertion as when he had been “opposed by a unanimous majority throughout (Asch 5).” If we don't cut against the grain, it may be no one else will have the resources to choose what they believe to be right, and this can setup a system where many a good idea or decision, are silenced. And it was also found, when the subjects partner did not desert him to join the majority, but rather left the experiment altogether, that the effect it had on the subjects confidence to answer independently remained, if diminished somewhat (5). Asch states it best when he proclaims “ That we have found the tendency to conformity in our society so strong that reasonably intelligent and well-meaning young people are willing to call white black is a matter of concern (5).” With his serious conclusion I am brought to a state of alarm. This nature resides within us as a species to contradict the ethical and moral standards that our logical and compassionate minds dictate to us as right, frightens me. That we have the potential to unwittingly contribute to ends and means which we find abhorrent should ring an alarm in all of our hearts. But I have hope that with this knowledge of a potential propensity for evil, gives us the means to guard against it's formation. I announce that disobedience is a virtue, even if you're dead wrong. It lightens the load of social pressure on the next man, to make his choice out of an honesty to his own beliefs.