OMAM Study Guide Advanced - Sprowston Community High School

advertisement

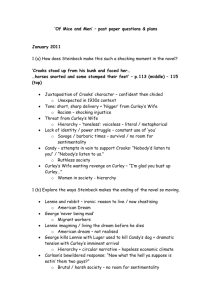

John Steinbeck’s ‘Of Mice and Men’ – Advanced Study Guide These notes will be useful to you only if you feel yourself capable of achieving a top grade and if you know this story and the techniques of story writing well. The notes cover advanced literary ideas, although many are explained where necessary. “The ancient commission of the writer has not changed. He is charged with exposing our many grievous faults and failures, with dredging up to the light our dark and dangerous dreams for the purpose of improvement.” John Steinbeck speaking at the presentation of his Nobel Prize for Literature in 1962. SECTION / CHAPTER ONE STEINBECK’S USE OF DIALOGUE AND ‘NARRATIVE VIEWPOINT’ To understand Steinbeck’s way of writing ‘Of Mice and Men’ – the highly effective ways in which he makes us believe so completely in his fictional characters, their lives and their actions – the close reader will need to detect that the author’s point of view is carefully and purposefully chosen. Steinbeck decided not to construct this novel so that all the action is directly perceived only through one particular character (i.e. as in a ‘first person viewpoint’ – “I…”); instead, he uses a subtle combination of a usually unobtrusive and subtly effective (and amazingly trustworthy) ‘third person narrator’ (who is able to speak about the characters from outside the story as ‘He…’ and ‘They…’) along with a good deal of lively and realistic-sounding dialogue (“Ya crazy bastard…!”). This absorbs the reader into a very believable world of the ranch and its characters. The choice of language is important, too, with a heavy reliance on colloquial rural dialect that creates an undoubtedly realistic effect. Such trust and realism is crucial as, for other important reasons discussed later, the author has chosen rather ‘simplistic’, almost stereotypical, character types. As with much of the rest of the novel, a good deal of the first section (Steinbeck put in no actual chapters, even though the publisher has in your edition) is written in dialogue. Authors can easily tell their reader what a particular character is like, but showing, through, as here, dialogue and vivid sensory description (i.e. describing what is seen, heard, felt…) creates a far more believable and convincing ‘portrait’ in the mind’s eye – add to this the ‘personified’ description Steinbeck uses with careful choices, especially of verbs and adjectives, and the effect is to have a strong emotional pull on the reader – for example, he personifies the mountains as “strong”, the branches as “recumbent” – all ways of describing nature such that it appeals to us almost as if it could somehow choose and act for our use and benefit, rather than just ‘being’. Think carefully about this: nature just “is” – it has no volition or feelings. Look closely at the first few pages again – can you see how this style of ‘showing’ combined with subtle ‘telling’ about a character has the effect of convincing us that we have ‘made up our own mind’ about a character or a scene, rather than having to accept the narrator’s words. Look closely about the kind of emotions and feelings the writing style generates: how are you feeling at this point about the Salinas Valley; about George and Lennie; about Steinbeck as the narrator? A little later in the first section, Lennie threatens to leave George and live in the hills – well, these hills are made to sound very inviting from Steinbeck’s early description… but George points out that Lennie would not survive long (and neither would we). Why might Steinbeck have fooled us that nature is so inviting (almost like a holiday brochure description)? It is, of course, nothing more than an illusion – a literary device which Steinbeck plays on our imagination; but it works. The third-person narrator of this story is often not even noticeable. Steinbeck’s own language choices are interesting when he is narrating: he often chooses to slip in the occasional highly formal or complex word into the narration; this has the effect of building trust in him as a highly educated narrator – another important literary device that is well chosen as his intention is to convince us to accept his point of view about this all-too-real seeming society; again – he succeeds admirably. LENNIE’S SPEECH The first section demonstrates Steinbeck’s ability to use speech to help define character in a very convincing and emotional way. Lennie, with the mind of a child, would be expected to speak like a child; and the reader finds that, sure enough, he does. A look at the grammatical structure of the sentences of Lennie’s friend, George, will show that they are far less basic than those of Lennie. When Lennie does use a more complex sentence, it is only as a copy of what George has just said. Such an instance occurs when Lennie frequently interrupts George’s telling of the ‘Dream’ story; the big man knows the tale so well that he is able to reproduce George’s language exactly: ‘…because I got you to look after me, and you got me to look after you.’ The repetition and simplicity, of course, adds a deep note of pathos or sadness. By the end of the first section, we already feel deeply for these two men – outsiders from society, cast onto the scrapheap of life. Poor and working class as they are – we feel they deserve better. Even one of their own class – the bus driver – treats them shamefully, dropping them off miles from the ranch under a lying pretext. One of the points Steinbeck is perhaps making is the way even workers ‘fight’ against each other unhelpfully, rather than recognising that the workers outnumber the “bosses” massively – if only they got together instead of fighting each other? The American capitalist hierarchy of boss downwards has a vice-like grip on this society – which is a kind of microcosm of a 1930s American rural society. SECTION TWO THE NOVEL AS A PLAY SCRIPT This entire section takes place in the bunkhouse and, if it were a play script, it couldn’t have been written in a manner more appropriate for the stage: its form and structure are so simple and direct. After the two men have entered the bunkhouse, preceded by ‘the old man’ (whom we only learn much later by his name, Candy), every new character enters by the same door, one at a time – as if on a stage. This is entirely intentional, as Steinbeck – a biologist by training – had in mind the ‘ritualistic’ behaviour that was an ingrained part of the lives of these ranch hands. He had reason to want to emphasise this as a means of reminding the reader that the way these men act is not entirely through unguided free will. Ritualisation (i.e. doing things in the same way, time after time without thought) acts to make certain ways of living seem entirely “natural” when, of course, they are not (we all have many comforting rituals if we stop to think about it). Such ritualisation so easily becomes a seemingly natural part of life and creates ‘modes’ or ways of existing within a particular society, our own included (you could consider as a parallel, the ‘institutionalisation’ of old people in old folks’ homes). This is important if we consider the way Curley feels he must act, for example, or the Boss and so on – they feel they have roles to play – you could see this action almost as instinctive – and that is akin to the ways animals act, without thought or conscience. Of course, humans are not animals – but in this story, much of what goes wrong is when humans act without sensitivity, without thought and without reflection – that is, when they act more like an animal, relying on instinct. These modes of behaviour are deeply ingrained and surprisingly consistently patterned. Steinbeck was well aware of Charles Darwin’s theories of evolution. These had shaken the world’s views of humans – in this story, there seems to be a range of “evolved” humans shown, from Lennie who was born with a damaged brain and cannot help his animal-like instinctive behaviour, through to Slim, who is shown as a highly evolved human being. It is worth thinking about how other characters fit into Steinbeck’s evolution hierarchy. The reader will gain a greater understanding of this section by recalling that Steinbeck, although considered a ‘realistic’ writer, also lends to his writing a strongly poetic or symbolic element – not only when he describes the processes of nature but also when he presents human relationships. In the novel ‘nature’ is often compared and contrasted to ‘civilisation’ (the ‘nature versus nurture’ argument has long fascinated sociologists: are we born with character traits or do we learn them?). Steinbeck admired many of the particular ‘community’ qualities inherent in the ‘old ways’ of cowboy ranch life – he came from Soledad himself and had seen it at first hand; by the mid-1930s however, he saw that this traditional way of life was being warped and threatened by what he perceived to be the increasing greed for profit of the farm owners (capitalism – where costs are reduced to a minimum, and profits are maximised), by the influx of cheap labour created by the Great Depression and the Great Dust Bowl, and by the increasing mechanisation of farm work. However, he felt that many of the enduring good qualities in this way of life were still apparent, qualities of behaviour that relied on modes of ritual shown through particular courtesies, acts of playfulness, games, the devoted enjoyment of natural processes, an admiring concern for sexuality, a pattern of warm-hearted appreciation of goodness that is completely outside of any concern for property or wealth. Such ritualistic descriptions within the novel (‘setting down’ to talk together, the sharing of food and drink, the game of horse shoes, and so on) act as a kind of ‘symbolic shorthand’ to help the careful reader understand a character, his actions and ways of thinking and living more fully. Steinbeck believed strongly in the influence of myth and archetype (Carl Jung, the eminent 20 century psychoanalyst, developed and proposed these ideas - that certain all-pervading human thought patterns and ways of behaviour were universal and ancient in origin. It was as if such ways of thinking emanated from a kind of ‘universal genetic pool of thought’. Jung termed this, mankind’s ‘collective unconscious’. Such archetypes create particular patterns of thought and have there origin in ancient myths, stories and legends: stories of good versus evil, of the brave warrior, the evil dragon, the wicked witch, the temptress, the happy family, and so on). Steinbeck felt that such universally held ideas were important to the way humanity behaved and he incorporated some of these ideas within this simple story because he knew the power they have on readers of all ages. ‘OF MICE AND MEN’ AS ‘ALLEGORY’ An allegory is a story in which its reader is aware of ‘hearing another story’ being told at the same time as the ‘real’ story is read. The allegorical story (the one we feel we are also ‘reading’…) is about real life; it is as if the imaginary fictional story is a parallel for reality. Unlike many ‘realistic’ novelists, Steinbeck does not build up his characters through a wealth of detail: he chooses one anecdote (small story), one telling character trait, one item of clothing and allows each of these to take on what can be called a symbolic power in the definition of the essential quality of that character. The small snippet, snapshot or ‘vignette’ he gives the reader acts to symbolise something much larger (and which we can relate to real life). This is why ‘Of Mice and Men’ is said to have an ‘allegorical quality’. This simply means that the novel tends to single out ‘primary human character traits’ – the characters seem, almost, to be examples of ‘standard’ character types taken from our own society: it is as if the ranch in Soledad becomes a kind of ‘microcosm’ (a small replica…) of US rural society in the mid 1930s, and as we read the novel, we seem to be reminded of a ‘second narrative’ – an allegorical narrative – unravelling itself at the same time and in parallel: this ‘second layer’ of narrative concerns not the ranch but life in mid 1930s America – and to a very real extent, life today for us readers of the new millennium. This story has become a classic just because it deals with primal human and society behaviour to which we can still relate, today. It has a timeless quality: man’s behaviour towards man is slow to change. Steinbeck’s use of allegory and stereotype risks the criticism of the story being too superficial as, in real life, people are not at all so straightforward – they cannot be reduced to such simple character traits; and their lives should not, perhaps, be reduced to a narrative form in which only selected events are told, from a single viewpoint, and which all appear to ‘connect’ in the reader’s mind (narratives always simplify characters and events to a state where ‘this follows that because of that’ and so forth. If only life were so simple!). But Steinbeck new the compelling power of narrative story telling over readers both to entertain and, importantly to convince and persuade. We tell of and hear about life itself – not just fiction – in the same form – as a narrative (i.e. when we tell of events in our lives, we create the same narrative structure as a fictional narrative - a linked beginning-middle-end; and we make certain people a hero and others a villain, just as in fictional stories). Steinbeck uses his great intelligence, art and craftsmanship with words and he knew that his readers would – for deeply held psychological reasons – accept this ‘allegorical mode of narrative story telling’ – developing even greater empathy and sympathy for his entirely fictional characters by his use of it. THE BOSS AND CURLEY Section 2 contains only two references to the Boss, both short and both conveyed by Candy, the old man. He first tells George that when the boss gets angry, he takes it out on Crooks, the black stable buck; the reader gets the impression that Crooks is a kind of ‘whipping boy’ on whom the Boss chooses to take out his anger. Right after this statement, Candy tells a story about the boss, who showed his ‘generosity’ the previous Christmas by bringing in a gallon of whiskey to the bunkhouse. In the fun that followed, the stable hand was allowed a rare visit to the bunkhouse and, for everyone’s amusement, a fight had been arranged between him and some other worker. Since Crooks had a ‘busted’ back, SJC 2000 – Rev. 03/03/2016 – OMAM Advanced Study Guide Page 2 his opponent was forbidden to use his feet in the fight – in the interest apparently of a ‘sporting’ match. The fact that the stable hand wins (and note that Steinbeck has him winning the horse-shoe games, too) seems secondary to the reader’s impression of the hidden and manipulative malice (i.e. the hatred towards Blacks) operating from the top (i.e. the Boss) downwards. It is directly after the telling of this story that the Boss walks in, and his behaviour with George and Lennie in their brief conversation together derives its overtones largely from what the reader has just found out about the way he treats Crooks. By saying very little and saying it so subtly, the reader is already against the Boss – and taking on Steinbeck’s ways of seeing the world. Another character in this section is defined through the mention of one carefully observed trait, which comes up three times in the course of just two pages. Curley, the boss’s son, is described generally – thin, short, young, brown eyes, tightly curled hair (don’t miss the similarity – temper wise, too – with George, but also, importantly, the close physical similarity to Crooks – dark skin and tightly curled hair) – but the author also notes that Curley wears a work glove on his left hand. The reader senses him immediately as an unpleasant character. After his very brief visit to the bunkhouse, Curley leaves. Candy, the old man, talks about him, telling George that the boss’s son has done quite a bit in the ring and is very ‘handy’ with his fists (physical and psychological violence are major themes of this novel – consider the number of characters involved in violent acts). The old man continues by stating that if Curley ‘jumps’ someone, a bigger man, and licks him, everybody praises him as a game guy; on the other hand, if Curley loses, everybody says that the bigger man should have picked on someone his own size. By this early stage, the reader, remembering the image of the glove on the left hand, has begun to conceive of that glove as a symbol – something that stands for something far larger, something about the man himself and his qualities as a human being – and about other men in the real world whom we can relate to who are like this man, Curley. The final allusion to Curley’s glove, also made by the ‘old man’, discloses the information that it contains Vaseline – Curley is keeping his hand soft for his wife, according to the old man. Thus the symbolic value of the glove is increased: to the reader’s sense of Curley as an unjust, immoral man – a ‘creature of power’, is added obscene and crudely sexual suggestions of some of the qualities of the Vaseline – smoothness, secrecy and even – a cloying, hidden effeminacy behind the tough fighting exterior surface. It is as if Curley’s determination to ‘prove’ his masculinity might well be a foil to hide his real nature. After all – compare him with Slim; is Slim trying to prove anything? Curley’s crude hint that Curley and Lennie might be homosexual adds to this very subtle hint. Another point of interest in the creation of Curley is the parallel with, not just Crooks in his appearance, or George in his shape and size (and temper!), but in the way Curley dresses just like – indeed exactly copies – his father: the belt, the boots and the spurs he has on his boots – even the way he holds himself with his thumbs in his belt loops. Who else copies someone closely? Lennie – he copies George. But he can’t help it, he can’t think for himself. What is Curley’s excuse – or, more important, what is Steinbeck suggesting about the way we just copy what already exists – and about how slowly, therefore, society will change if this inability to think for ourselves continues. Again, the importance of a character such as Slim becomes obvious – a self-possessed, self-determining individual: a highly evolved human being able to control any animal instincts that might arise. CLOTHES AND THE MAN In this section, the way people are dressed helps the reader define character: the boss, we are told, is a little man, a stocky man. He wears blue jeans, a flannel shirt, a black vest (unbuttoned), and a black coat; his thumbs are in his belt; he wears a Stetson hat – and, most importantly, he wears high-heeled boots in order to prove, as the author tells us, that he is ‘not a labourer’. The reader is prepared in this way to feel dislike towards the boss: the ‘old man’ (later named as Candy, but at this stage a kind of ‘voice’ telling of certain events in a non-judgmental way) has just described the incident of the gallon of whiskey; and thus the unsubtle comment about the high-heeled boots begins to draw the reader’s sympathy away from this wealthy, propertied symbol of the boss and toward the poorer workers (we are clearly being persuaded through careful and subtle narration, description and dialogue to share Steinbeck’s way of seeing the world). As for Curley, who enters next, besides the glove, he wears exactly the same kind of boots as his father. Curley’s wife wears heavy lipstick, red fingernails, red shoes decorated at the insteps with little bouquets of red ostrich feathers. Her voice is ‘nasal’ and ‘brittle’. Slim enters next: his hair is long, black, and damp; at the moment that he enters, he is engaged in combing it straight back. Slim does not wear high-heeled boots. We are told only that he has on blue jeans and a denim jacket and a Stetson. Slim is described as walking with ‘a majesty found only in royalty and master craftsmen’, and owns a manner ‘so grave and profound that all talk stops when he speaks’. His speech is ‘slow’ and ‘creates understanding’; his ‘hatchet face’ is lean and ageless; his hands are large and lean. He is ‘the prince of the ranch’. And with that one word, ‘prince’, the careful reader can again perceive a particular symbolic quality to this novel as they are reminded of ancient stories such as the epic, ballad and fairy tale in which good and evil can be readily identified and in which ‘good’ always prevails over ‘evil’. The actions of the good and the evil in such ancient tales were always easy to understand and it is a wonder that this story, with its echoes of such well-known and ancient story-telling forms, can retain it’s reader’s interest for the knowledgeable reader would easily be able to guess the outcome. Yet, paradoxically, it is these same rituals that ‘hypnotise’ (even control our ways pf thinking and seeing the world – such is the power of narrative) us, too, just as the ‘dream ranch’ never fails to ‘hypnotise’ and control Lennie with its narrative and imaginative power: so – just like the simpleton Lennie – we, too, quite amazingly really, remain fascinated by the roll of (entirely fictional!) events: the clash of good (Steinbeck’s version of what is good) versus evil (Steinbeck’s version of what is ‘evil’), of innocence versus experience, and of nature versus civilisation as we give ourselves over to the enjoyment and strange security and comfort that this ‘ancient’ modern story brings in its thrall. SECTION THREE MORAL HIERARCHY The characters in the story form a kind of moral (and maybe of a Darwinian evolutionary) hierarchy both directly and indirectly. Slim constitutes the high point of such an evolutionary hierarchy: he looks at George and Lennie ‘kindly’; he talks to them ‘gently’; his tone is ‘friendly’ and invites SJC 2000 – Rev. 03/03/2016 – OMAM Advanced Study Guide Page 3 confidence ‘without demanding it’. Implicit in this last phrase lies the kernel of Slim’s moral ascendancy. He does not demand, or manipulate; he is not self-seeking, has no vested interest. He derives satisfaction from his physical work, which he does supremely well, and does not ask for reassurance from others. Curley’s Wife wants recognition, wants flirtation, and wants commitments of interest. The boss wants reassurance too; his suspicious nature cannot be satisfied with its own perceptions; he is on the lookout for trouble; he wants to be told about the relationship between Lennie and George; he wants not to be fooled; he wants to keep on top of everything; he wants to impress the pair with his power. Curley, less settled, less mature and more extreme than his father, wants even more: he wants to manipulate physically; he wants to set up situations for testing his strength (about which he is, presumably, unsure); he wants not only recognition but also deference. It is interesting to note that, if Slim constitutes the high level of ethical perception in the scene, the other significant moral generalization made is uttered by Lennie, who says, ‘Le’s go, George... . It’s mean here.’ Although Lennie lacks understanding, he is, in fact, able in his simple way to act as a kind of ‘moral antenna’ – an animal-like survival instinct, perhaps? Lennie’s comment underlines Steinbeck’s dislike of deceitfulness or affectedness in the way people behave and a corresponding love of simple goodness and honesty. THE IMPORTANCE OF SLIM In both of the major episodes in this section, the central figure is Slim. He is central in the contexts of morality and authority and self-respect, not just in terms of pure physical activity. Carlson’s continuous complaints about the old man’s smelly dog might have had no concrete effect had it not been for Slim’s intervention. In the second event, the dispute with Curley, probably neither Carlson nor Candy would have dared to attack Curley verbally without Slim’s tacit agreement. And it is these verbal assaults that move Curley to take cowardly revenge on Lennie, who had had absolutely nothing to do with the situation. So we must turn our attention more intensively to Slim, the ‘prince’, who appears to be involved in the entire section in a consistent and somehow utterly essential manner. That he is merely the central figure, however, is debatable: Slim’s role could be effectively compared in some ways with those of a psychoanalyst and a judge: the patience and professional passivity of the first can be contrasted with the legal involvements required of the second. SLIM’S CHARACTER In the beginning of section/chapter 3, George finds it possible to tell Slim his most incriminating secret: the story of what happened in the town of Weed when Lennie got into trouble. Slim makes an apparently idle comment expressing interest in the closeness between the two men, but he does not ask any questions: he does not respond judgmentally – he simply understands. This is the third occasion in which this matter has come up. On the first, early in Section 2, the boss immediately communicated his disbelief in George’s capacity for altruistic concern for Lennie: ‘What you got on this guy?’ For the boss, a belief in such honest and sincere human qualities would lead to a weakening of those traits that establish him as an owner, hirer, manipulator… capitalist. Later, when Curley arrives on the scene, he is convinced that a friendship between two men is not possible without homosexuality being a factor, ‘It’s like that is it?’ In Slim’s case, however, such a belief is part of his personality and it contributes – importantly – to his use by Steinbeck as a kind of Jungian ‘archetype’ or ‘primitive, ethical symbol’: the reader ‘believes’ (because of the existence of such Jungian archetypes or mythical beings as Slim – the ‘prince’) in the goodness of Slim for deeply-rooted psychological reasons. A ‘real smart guy,’ he says at one point, ‘ain’t hardly ever a nice fella’ – and we find ourselves believing him. But Slim’s main attitude in the early part of this scene is represented by his tone. His comment about the two men is a ‘calm invitation to confidence’. When George, eager to talk but wary, remains momentarily silent, Slim ‘neither encouraged nor discouraged him. He just sat back quiet and receptive’. Slim’s comment after a particular disclosure by George is simply, ‘Umm’. At one point George starts to tell Slim what happened in Weed. Alarmed at the potentially incriminating and dangerous confidence he is about to communicate, George stops himself saying more. Slim asks a simple question here, but ‘calmly’. Slim’s eyes are ‘level and unwinking’; he nods ‘very slowly’; again, his ‘calm eyes’ follow Lennie out the door when he goes to return the pup. Steinbeck gives Slim an almost mystical quality to his wisdom and detachment from events. Yet, almost paradoxically (for life is, if anything, a paradox) he has a level of cool objectivity that fully coexists with an awareness and acceptance of natural biological processes: an awareness of a life in which the old must die, the young must get old, and one generation must give way to the next. So, when Slim says, ‘That dog ain’t no good to himself. I wisht somebody’d shoot me if I get old an’ a cripple’, he is speaking out of the second half of the paradox that is human nature: his acceptance of biological necessity clashes with his sentimental attitudes of mind. SLIM’S FUNCTIONAL ROLE To understand Steinbeck’s role for Slim, we should look more closely at the scene dealing with the problem of Candy’s old dog. What are the arguments that are marshalled by the old man in support of his desire to keep the animal? He’s been around the dog so long that he does not notice the ‘stink’; he’s had the dog so long and likes him so much that he can’t stand not being with him; his fond memory of the old dog’s prowess as a sheepdog compensates for the dog’s present near paralysis; he doesn’t mind taking care of the dog; the shot might hurt the dog. Carlson, the animal’s arch-enemy, counters all these objections: the dog’s no good to Candy; it stinks ‘to beat hell’; the animal’s all stiff with rheumatism; the dog’s no good to himself; Candy is being cruel to the dog by keeping it alive; the shot would not hurt the dog for even one second. Structurally, Slim’s judging of the situation is worthy of the Biblical Wisdom of Solomon: the dog is no good to himself, but Candy is to get another one. Although Slim is not the first to suggest that the old man take one of the pups, and although he is not the first to suggest that the dog is no good to himself, he does make one very important observation, unique to him: Slim comments that he wishes ‘somebody’d shoot him if he ever gets old and crippled’. By including himself in the human situation, Slim effectively counteracts both the harshness of his own SJC 2000 – Rev. 03/03/2016 – OMAM Advanced Study Guide Page 4 biological dictum and the harshness of Carlson’s self-righteous demands. Ironically, Slim himself is the living refutation, in this instance, of his previous statement that intelligence and generosity do not go together. GEORGE AND THE MORAL SENSE At one point in Section 3, George finds it possible to tell Slim a story of the greatest importance in the development of his relationship with Lennie. The tale is significant not only on the level of human connections; it also stands out as a kind of fable of moral good-living, concerned with the uses of power. The growth of an ethical sense implies the renunciation of the use of power in many instances, when such use can be perceived as hurtful to other human beings. George tells Slim that one time a group of ‘guys’ were standing along the bank of the Sacramento River. George, feeling ‘pretty smart’, turned to Lennie and ordered him to jump in. Although he could not swim, Lennie immediately obeyed – and nearly drowned before the group recovered him from the water. And then, George adds, Lennie was nice to him for pulling him out: he says, then, that ‘I ain’t done nothing like that no more’. This circumstance holds little ambiguity. Its moral point is clear. Later on, however, an incident occurs that questions the constant capacity of any man – no matter how full of good will – to make decisions adequately about the proper and improper uses of power, especially in an urgent situation. After Curley first struck Lennie on the nose, the big man retreated to the wall. Slim, disgusted and infuriated by the unprompted assault, jumped up cursing Curley and saying, ‘I’ll get ‘um myself’. George had an important decision to make instantly. He had already told Lennie to ‘get’ Curley, and the big man had been too frightened to respond appropriately. At this point, would it not have been a sound idea to allow Slim to take care of Curley? George knew that Lennie, once enraged, was uncontrollable, and he knew that Slim could dispose of the boss’s son. He did not simply ask Slim not to mix in; he ‘put out his hand and grabbed Slim. “Wait a minute,” he shouted.’ An objective observer might note that George’s personal desire for revenge against Curley, whom he already disliked, overruled a more sensible course of action; George’s response was instinctive and all-too-human (except that he – cowardly? – used Lennie to carry it out). In addition, since George did not know when Lennie would finally respond to his companion’s permission to strike back, the big man might very well suffer greater punishment than if Slim had immediately interceded. If the analysis is pursued further, a reader might even wonder about the possibility that George’s choice might have been – ever so slightly – determined also by his hidden hostility to Lennie. After all, George, the ‘smart one’ of the two, had frequently complained grievously about the burden that Lennie had become for him. Whatever the truth, and however solid George’s active good will might appear, the incident suggests the imperfection of the moral sense in a complex and urgent situation. And as we shall see, Curley’s indelible hatred for Lennie, as a result of this incident, plays a very significant part in the tragic outcome of the story. TENSION A sense of tension in a narrative is vital in keeping the reader ‘on edge’, guessing what might happen next and feeling great satisfaction, or surprise, in whatever does. Section 3 is characterized by a great deal of tension. Between the discussions about the dog (and Carlson’s act) and the entrance of Curley intervenes a scene that adds a great measure of pathos or poignancy to the, by now, easily sensed and often foreshadowed overtones of the coming future disaster in. On four separate occasions, within the space of a few pages, George says, ‘Me and Lennie’s gonna roll up a stake’; ‘Me and Lennie’s rollin’ up a stake’; ‘Lennie and me got to make a stake’; ‘We gotta get a big stake together.’ The reader, unsure whether the $600 house and land even really exist, involved sympathetically with the hope newly born in the pair and Candy, reacts all the more actively in the context of the violence at the end of the section. SECTION 4 In this part of the novel we find gathered together the disinherited cast-offs – the outsiders – of the world: isolated, men born, as is sometimes said, under ‘the wrong star’. The scene derives a certain portion of its emotional power from an internal paradox; and it is the figure of Lennie that operates as the centre of this paradox. As Slim in the previous section constituted the ‘synthesizing’ force that brought everything together, so now Lennie – interestingly and analogously – operates similarly. Steinbeck creates in his reader an almost mystical belief in the social effectiveness – under appropriate conditions – shared by both the highest and the lowest intelligences: Slim and Lennie. Both individuals represent, in their own ways, the reality of goodness as an active principle in the world, the goodness arrived at through the vicissitudes (i.e. the ups and downs) of life and the goodness of innocence. Another very different parallel is that of George and Curley: consider their similarities and differences physically, emotionally and psychologically. CROOKS AND THE RANCH HANDS Significantly, we learn that only two men have ever visited Crooks’ room before. The Boss, of course, owns the room; it is perhaps not too much to say that he owns Crooks as well. His attitude toward the stable hand, as we have seen, is proprietary (one of ownership or use). We know, without being told, that the elements that underlie the Boss’s relationship with Crooks include the vicious sense of racial superiority and power, always potentially present, that Curley’s wife brings up as her withering threat against Crooks later in this section. We also know, without being directly informed, that this sense of superiority can be transcended only with great moral effort and difficulty, that it is a virulence probably shared by every white man on the ranch, to various degrees (and, is Steinbeck suggesting, shared by us all in different ways and circumstances, perhaps?). That Slim has been the only other guest of Crooks reinforces the reader’s belief in Slim’s capacity for such transcendence beyond that of the less evolved – ‘natural?’ – man. Without having been a party to any meeting between Crooks and Slim in the harness room, we can assume that Slim’s innate kindness, courtesy and detachment would probably operate as they did during his meetings and conversations with George. LENNIE’S VISIT SJC 2000 – Rev. 03/03/2016 – OMAM Advanced Study Guide Page 5 One of the keys to Lennie’s functional resemblance to Slim is suggested by the very wording of the initial conversation between Crooks and Lennie. When Crooks asks Lennie what he wants in the harness room, Lennie answers, ‘Nothing... . I thought I could jus’ come in an’ set (notice here a commonly used device in the story: a comforting use of a regional dialect word for ‘sit’), whereupon Crooks merely ‘stared’ at Lennie. Conditioned by decades of rejection and insults and contempt, the black man is ready to meet almost any manoeuvre, except this wholly unexpected one of free companionship. While it is true that Lennie goes to the harness room out of loneliness, it is equally true that no ‘learned’ hatreds or other similar stances of power or superiority forbid such a visit. Steinbeck is highlighting the fact that the processes of socialization into society (here very much a white society) include the processes of indoctrination into the rituals and beliefs (i.e. the ideologies) of such a society; since, because of his simpleton’s attributes, Lennie remains relatively immune to the first, he continues also unblemished by the second. This aspect of Lennie’s characteristic nature might very well be a romantic invention on the part of the novelist; however, by presenting Lennie in this way, Steinbeck again forcibly reminds us of his deep suspicions of social artifice (the affected ways society operates). NO AXE TO GRIND Steinbeck trained as a biologist and was utterly fascinated by the interaction of ‘basic’ biological human traits with complex, sometimes learned, psychological traits. With Steinbeck’s biological view of the world, a possibility for good exists, and it is interesting to speculate about the conditions in which good is able to function. An important element involves giving up the desire to meddle with others’ lives. This renunciation is a distinct factor in Slim’s makeup; it is equally a factor in Lennie’s arrival at Crooks’ room. But Lennie, not through will but through the impersonal processes of ‘fate’, does interfere in George’s life in a continuous and major way. We know that George shoulders this burden willingly, and we also know that he intermittently complains bitterly about it. Consequently, the narrative encloses the reader with more and more foreshadowing of doom for Lennie. Such a prophecy is implicit in the story of Lennie’s misadventure with the girl in Weed; the interest shown in Lennie by Curley’s wife; the destruction of Candy’s dying dog because the animal is biologically inferior, no good to itself, and a smelly intrusion into the life of the bunkhouse. Nevertheless, insofar as Lennie can be motivated by kindness, to that degree is he not only a man who can initiate human communion but also one who can breed it in others. CROOKS’ CHARACTER As Slim is a kind of nucleus for the ‘social cell’ that comprises the group of men in the bunkhouse in section 4, so Lennie becomes a similar nucleus for the world composed of Crooks, Candy, Curley’s wife, and himself. But there are complicating factors, primarily the resurgence of an almost sadistic malevolence on the part of the stable hand. A man who has almost never been treated as an equal will experience enormous difficulty in accepting the offer of friendship. Thus Crooks’ initial invitation to Lennie to ‘set a while’ leads very quickly to a situation in which the stable hand attempts to assert his newfound sense of power by baiting and frightening the big man. Power and powerlessness are major themes of the novel and were aspects of human psychology that fascinated Steinbeck – especially the changes in power structures that occur when groups of people gather (Steinbeck devised a theory that a kind of ‘group consciousness’ existed; that ‘group man’ was an entirely different creature to ‘individual man’, far more involved with power, machismo and hierarchy). Lennie, who begins as a figure of friendship, suddenly becomes for Crooks the perversely defined symbol of white man’s oppression: Crooks, ironically and perversely becomes a victim of the sudden departure of his own rational processes – as Lennie’s generosity brings forth Crooks’ invitation, so Lennie’s weakness invites Crooks’ buried furies; yet, the reader can understand and accept this – it adds to our ability to empathise and engage with the characters in the story. The pressures that condition the insulted and the injured brought by society are great; and those pressures unfortunately tend to bring out, not the noblest elements in a person’s nature, but the frightened child and the vengeful self. STEINBECK’S ‘INCONSISTENCIES’ As might be expected, those literary commentators who had themselves enlisted in a cause (either defending or attacking Capitalism), sharply criticized Steinbeck for what appeared to be dialectical (i.e. argument) inconsistencies. What readers failed to understand, and what they sometimes still fail to understand, is that Steinbeck had no fixed dialectic as such; his view, indeed, of social and economic struggle was based upon mythic and biological archetypes. The particular power-struggles he used as material for his novels were themselves symbols, or analogies, for vaster and more universal phenomena-patterns of force which belonged to the animal as well as to the human world, and which transcended both to approach a sort of Emersonian ‘Over-Soul’ or’ Universal Being’ which might be examined, but never explained. As a writer, Steinbeck sought for material that might serve as a metaphor for universal rather than particular ‘truth’; and he found such material not merely in the ‘Dream’ of dispossessed Oklahoma farmers, or wandering workers, or local ne’er-do-wells, but in the legends of King Arthur, and in the Biblical narratives of both the Old and New Testaments. For, Steinbeck recognised, the truly great ‘stories’ of mankind are never obsolete: that Christ’s crucifixion of 2000 years ago not only took place yesterday, but will be repeated tomorrow; that the decadence – and glory – of Rome is redefined by each morning’s headlines. As the ancient Roman poet, Ovid, noticed, ‘All things change but nothing is extinguished’. SECTION 5 STEINBECK AND CHILDHOOD Another interesting aspect of Steinbeck’s feeling about social artifice relates to the novelist’s attitude toward childhood. Soon after Lennie’s entry into Crooks’ harness room, Crooks tells him about his childhood: Crooks was born in California; his father had a ten-acre chicken ranch. White boys and girls would come to play at the ranch, and ‘some of them was pretty nice’. Crooks tells Lennie that his father did not like such a show of camaraderie, but Crooks asserts that he did not know until much later why. ‘But I know now,’ he adds. When he was a boy, his was the only black family for miles around. And now, he says, he is the only black man on the entire ranch. With the comparison between the society of his SJC 2000 – Rev. 03/03/2016 – OMAM Advanced Study Guide Page 6 childhood and that of his present situation, Crooks evokes a Steinbeckian belief clearly or covertly present in many of the novelist’s works: a belief in a kind of purity of motivation in the child’s world. Black and white children can play together, perhaps even love each other, but black and white adults must, of necessity, hate each other. The point goes further than merely an indication of sickness between races; the entire adult world is accused of guilt and complicity. Although Slim proves that it is not a general rule, the reader often feels that as a person becomes good, so he or she also becomes a child. There are overtones of Christian doctrine implicit in such concepts, as Christ said: ‘And a little child shall lead them’. LENNIE AND CURLEY’S WIFE What is the quality of the relationship between these two doomed people? Each is the direct agent of the other’s downfall. With one exception, however, each one is so utterly enclosed in his or her own fantasies that the two do not ever truly ever communicate with each other: they talk, and they even may share the illusion that they are speaking to each other – but it remains just that: an illusion. Each one is talking private thoughts aloud, each one is projecting nostalgia or hope or fear, but no actual exchange takes place. This absence of any meaningful rapport renders the scene almost unbearably moving. Two isolated creatures, each locked in his or her own subjectivity, pass by each other in an almost complete human darkness. Lennie’s predicament of course is clear. But what about Curley’s wife? Why is she doomed? It is true that she bears no particular physical or mental brand. But she is clearly part of that unconnected flotsam of social decay that has long attracted Steinbeck’s attention. She is adrift from the moorings of the middle-class society for which Steinbeck consistently shows he has little sympathy. But she has not met the challenge posed by such drifting in the manner typical of, say, the local ‘paisano’ or peasant subculture. So she is nowhere, supported by no family, nourished by no fortifying values, defined by no realistic ambitions. For the past hopes for a career in ‘pitchers’ on which she largely bases her tawdry attractions and her insecure sense of self are as illusory as her ‘conversation’ with Lennie. THE OTHERS Now let us examine the reactions of the various other members of this small society to the tragedy. One of the elements that strikes the reader as somewhat harsh, perhaps cruel, conceivably inconsistent, is the degree to which cold objectivity and even self-seeking characterize the reactions of various people. But we should by now have realised that such human responses, however cruel they seem on the surface, are often human defences against the pain of feeling. And Lennie’s act, in murdering Curley’s wife, was not the sort that carries with it cataclysmic surprise; in addition, we remember an aspect of Steinbeck’s world in which the impersonal processes of life do not stop or delay in the face of individual tragedy. In fact, it is the representative of that sense of the world who is the first to examine Curley’s wife’s body. Slim goes over to her ‘quietly’ and feels her wrist. He touches her cheek, and his fingers explore her neck. Only then does the silence break and the rest of the men start talking or shouting. Curley is the first one to cry out for vengeance. He has not even a split second of visible regret, mourning, or sorrow. His entire vendetta appears to be merely taking advantage of the death of his wife in order to seek a deeply held need for revenge: his anger and righteous outcries do not seem to come from any deep well within, only from the well of vengeance. Curley is such a coward that he must excite himself into activity: ‘He worked himself into a fury.’ And all the covert hostility that Curley had felt in relation to George now can afford to express itself; he gets pleasure from making sure that George becomes part of the lynching posse. And he does not even use George’s name when he addresses him: ‘You’re comin’ with us, fella.’ His shrewd mind is even able to furnish an apparently rational excuse for his urging his colleagues that they ‘give ‘im no chance. Shoot for his guts.’ To George’s plea that Lennie, not being sane and thus not responsible, should not be killed, Curley counters that Lennie has Carlson’s gun, a Luger, a supposition for which no one has any proof. As for Carlson, he is very much the same man who hounded Candy about the old man’s dying dog: his immediate response to Curley’s call for a killer mob is, ‘I’ll get my Luger’; no other considerations, no intermediary thought processes come between his view of the woman’s body and his running for the weapon: the response is instinctive – animal-like and un-evolved? But Candy’s world has fallen apart; whatever hopes he might have had of living in the dream ranch safe with George last only a few seconds. His first thoughts are for Lennie. He wants him to get away; he even argues with George about that point, stressing Curley’s vindictive cruelty. But the old man’s ‘greatest fear’ prompts him directly afterward to ask George pleadingly whether the two of them could still go to the ‘little place’. So it isn’t clear whether Candy’s concern for Lennie is as gratuitous as it seems. In the dim recesses of the old man’s mind might have strayed the idea that if Lennie were helped to escape, the three men might still find peace together. Ironically, it is Candy who is chosen by Slim to stay behind with the body, and although the old man is bereft now of all his lately wakened hopes, he can go beyond his own unhappiness at this instant. He squats down in the hay and looks at the dead woman’s face, and he thinks of Lennie, now the doomed quarry of a hunt: ‘Poor bastard’, Candy says softly. DEATH AND RELEASE Both George and Slim agree that a caged Lennie is an impossibility – society has not yet learned to cope with the ‘Lennie’s’ it produces. Lennie simply could not survive such conditions – and we are reminded of the plaintive taunt by Lennie to George that he could leave and live in the hills alone and, so, the men feel they must go out and find him. But it is, of course, George who is the great sufferer although a certain ambiguity does pervade his suffering: since Lennie alive exists in the cage of his own limitations and demands the special attention of the weak, death is a kind of release. It is a release in the same sense that Curley’s wife’s death enabled her to become ‘very pretty and simple’ in the absence of ‘the meanness and the plannings and the discontent and the ache for attention’. SJC 2000 – Rev. 03/03/2016 – OMAM Advanced Study Guide Page 7 SECTION 6 The first pages of this section contain a series of interesting and dramatically very effective parallelisms. As musical compositions often return at the end to some of the material typical of the beginning, so this section repeats some of the language and the setting of Section 1 – with significant alterations. PARALLELISMS AND ALTERATIONS The setting is the same as the one that began the novel, the pool by the Salinas River. Even the adjectives, which are the second and third words in Section 6 – ‘deep green’ – can be found in the same order in the first sentence of Section 1. Such specific and pinpointing details are appropriate here: we have discussed the poetic and symbolic elements inherent in the construction of this novel, and poetry is the concern for’ the right word in the right place’, and, indeed, for the ‘symbolic word’. As in Section 1, Steinbeck’s feeling for nature is manifest in the description of trees and animals at the pool. Note, though, that they are not merely generalized descriptions, but involve such specific names as sycamore, willow, lizard, snake, ‘coon, and heron. It is evening in both sections – the novel opens as darkness comes on, and it plays itself out as well in the coming of darkness. But whereas nature is wholly good in Section 1 – skittering lizards, sitting rabbits, deep-lying crisp leaves – the animal symbolism of Section 6 suggests the continuity of those impersonal biological processes that Steinbeck has hinted at throughout the story: a water snake, gliding the length of the pool, reaches the legs of an unmoving heron, who instantly grabs the reptile and eats it; as snakes eat insects, so herons eat snakes: it is simply the truth about the animal world – a world to which man might pretend he does not belong, but which if he does he fools himself – man, here, in the shape of Curley, or George, or Lennie. The wind suddenly rushes – Steinbeck uses the effective literary device of ‘mental landscape’ – as the heron makes its catch, then all is quiet again. It might not be too much to see in this complicity of nature: the heron stands again in the shallows, ‘motionless and waiting’; another little water snake swims up the pool. Yet more parallelisms can be seen when Steinbeck describes Lennie in his sudden approach to a bear; but whereas in Section 1 he was seen walking ‘heavily... dragging his feet’ as a bear does, now he comes ‘as silently as a creeping bear does’: he is still ‘a bear’, but now a frightened one. In Section 1, Lennie ‘flung himself down’ to drink from the pool, snorting into the water ‘like a horse’; but now he ‘knelt down’ to drink. There are no horse-like noises now; he is ‘barely touching his lips to the water.’ In the first instance his animal passion for water was so concentrated that he would not have noticed any noise; as a matter of fact, George had to shake him free of the water. In this scene, however, the sound of a little bird skittering over dry leaves causes Lennie immediately to jerk his head up, all attention focused on the source of the sound. When he finishes drinking, he sits on the bank, unconsciously emulating his posture in Section 1, when he embraced his knees in imitation of George. In fact, the entire scene is largely composed of restatements of past events and attitudes. In this case we discover not only the parallelism between the beginning and the end, but also recapitulation of elements from other parts of the novel. Among them two are most important, and in the context of this final scene most poignant. They consist of the two stories that constitute the symbolic polarities of George’s attitudes toward Lennie. Again, as in the case of the shifting parallelisms described above, the effectiveness of the repetitions is enhanced by subtle variations. George, miserably full of the knowledge of his eventual act, is unwilling to scold Lennie; but Lennie, who is attuned to scoldings no less ritualistically than he is to the ‘Dream’, actually begs George to tell him off, to recount again how easy life would be without Lennie, how George could take his $50 a month and do what he wanted with it. But George cannot finish this scolding and at Lennie’s behest goes on to the final telling of the ‘Dream’. Thus the entire last scene, until the entrance of the men, proceeds by way of indicating symbols. There is no direct foretelling of the killing, and the movement unwinds itself almost like a grave, heartbreaking pageant. In this connection, it is interesting to observe that just before George makes his first effort to kill Lennie, he takes off his hat and suggests that Lennie do the same. ‘The air feels fine’, he tells Lennie. On a practical level, George may have made the suggestion in order to have a clear target; but, he could have probably done without this last order. There is another overtone here, vague echoes of the symbolic usage that dictates that men remove their hats in church; that they remove their hats in respect: George, as it were, starts mourning for his friend from this point. LAST WORDS The final words of carefully contrived narrative stories such as this one are usually written with great care. They constitute an important part of the reader’s last impression and must consequently communicate the author’s sense of a deep-lying appropriateness. Steinbeck could easily have ended this novel at one of several points and still have established a dramatic finish. He might have concluded with the conversation between George and Carlson, in which George tiredly assents to Carlson’s version of the killing. Or Steinbeck might have ended at the point of George’s departure with Slim, as Slim assures his companion that there had been no choice, that what is, is, that what had to be done was done: that in such a crudely capitalistic society, where a man’s worth is only measured by his capacity to create profit for a boss, left little option but to end Lennie’s life. But Steinbeck chose to finish the novel with Carlson’s comment to Curley: ‘Now what the hell ya suppose is eatin’ them two guys?’ Thus the ‘Dream’ ends on a jarring, harsh, cruel note, typified by lack of understanding and empathy. The statement is a token of extraordinary moral denseness, and perhaps by using it in this final position, Steinbeck was attempting to get across to the reader a sense of the implacable and dark disinterest of the world in the tragedy of the individual. Whatever Steinbeck’s intent, this last comment leaves the reader with a powerful sense of the world’s iniquity. SJC 2000 – Rev. 03/03/2016 – OMAM Advanced Study Guide Page 8