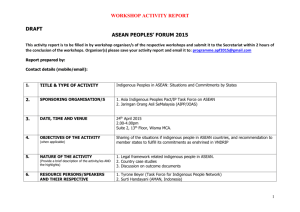

The Obligation to Report on Indigenous Peoples

advertisement