Why did Britain follow a policy of appeasement in the 1930`s? With

advertisement

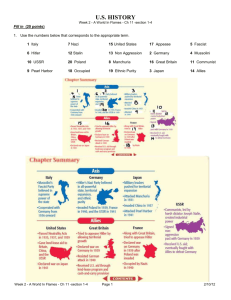

Why did Britain follow a policy of appeasement in the 1930’s? With their governments struggling to cope with domestic problems, both Britain and France lacked the determination and economic resources to challenge developments in Germany. As a result, both countries sought to avoid conflict and opted for compromise and negotiation which resulted in appeasement. Public Opinion & Pacifism Growing body of evidence that people were opposed to war: October 1933: a by-election in the London constituency Fulham East showed that the Labour Party candidate, who promised to support disarmament, overturned a large Conservative majority to win the seat by 5000 votes. Result arguably reflects widespread pacifism. 1933 Co-operative Women’s Guild produced first white poppies for Armistice Day. Argued world was drifting back to war and this was their desire for peace. 1934 Dick Sheppard – pacifist clergyman wrote to Manchester Guardian and other newspapers inviting men to send postcard to him promising to “renounce war and never again support another”. Received 2500 replies within 2 days/within few weeks 30,000 had made this pledge. Peace Pledge Union – as it became known – had over 100,000 members by 1936 including famous figures such as poet Siegfried Sassoon, author Aldous Huxley. PPU had its own newspaper – circulation 22,000 Oxford University Union, 1933: supported pacifism. Debated motion “This House will under no circumstances fight for King and Country”. Motion supported 275/153 votes. 1935 Peace Ballot (organised by League of Nations): voters asked to vote on various issues concerning peace. Over 11 million participated, revealing overwhelming support for collective security, LoN and disarmament. Further survey in July 1937 revealed 71% of British people thought that supporting LoN was best way of keeping peace. Memories of WWI remained powerful – Books like Goodbye to All That (1929) and 1930’s film All Quiet on the Western Front intensified widespread rejection of war. Worries about potential of air power. Development of bomber had changed nature of warfare permanently. Great fear it would be used against civilian populations as well as industrial and strategic targets. Stanley Baldwin “ realise that no power on earth can protect him from being bombed....the bomber will always get through” Reality of bombing raids in Abyssinia and Guernica combined with graphic depiction of fictitious bombing of London in the 1936 science fiction film Things to Come left a lasting impression of horror which few were prepared to ignore. Threat of Communism For many Communism was most pressing problem of the 1930’s Communism is a theory advocating that people get rid of their own property and goods are owned by everyone. Flowery definition sounds good from outset = everyone should be united and live in common. Darker side: a country that has communism does not have the same freedoms as those in democratic countries. There is no right to own property, there are few rights to speak out against the government, there are few freedoms of press, and other freedoms we hold dear to our lives. ‘As a result, Germany seen as best hope of preventing spread of Bolshevism...Nazism was preferable to Communism’ (Ian Kersahw, Making Friends with Hitler, 2004) Lord Rothermere, wealthy newspaper proprietor, expressed popular rightwing view when he wrote in Daily Mail Nov 1933 “sturdy young Nazis” were “Europe’s guardians against the Communist danger” Economic Concerns Britain cut defence spending after WWI Supported as believed it would reduce likelihood of war and make further defence spending cuts possible. In 1932 the ‘10 year rule’ (introduced in 1919) was suspended: policy would no longer be based on assumption that there would be no major war in next 10 years. 1933 Defence Requirements Committee set up by Ramsay MacDonald (Prime Minister) to make recommendations about future defence spending Britain couldn’t afford to increase spending on armed forces Early as 1934 British government warned from Committee of Imperial Defence (C.I.D) that Hitler was ‘the ultimate potential enemy’. Chamberlain as Chancellor of Exchequer at that time was in charge of Britain’s economy. As Britain was in a depression, he knew that jobs and better housing were priorities for the British public. Public had votes and Chamberlain knew they would not support large scale military spending. They wanted ‘butter before guns’ By 1937, military balance of power not in Britain’s favour and economy still weak. Without military resources was there an alternative for Britain other than appeasement? Attitudes to the Versailles Settlement Hitler committed to a revision of the Treaty of Versailles and British politicians had been critical of aspects of the Treaty for a long time. Between 1933 and 1936 there was widespread acceptance that Hitler’s demands relating to the Treaty of Versailles were justified. In 1935 Britain had even negotiated a change in the treaty with the AngloGerman Naval Agreement. People recognised that almost complete disarmament of Germany had left it vulnerable to attack At same time, Hitler’s skilful use of propaganda succeeded in convincing people that he was looking to restore Germany to its rightful position in Europe, but that his ambitions did not threaten European peace. Thus, Hitler’s demands were seen as justified. Attitudes to Hitler and failure to recognise him as a threat Attitudes to Germany changed considerably between 1933 and 1937. As a result so too did attitudes towards appeasement. Frank McDonough argues that by 1936 ‘Nazi Germany was no longer viewed as a weak and defeated power but as a menacing threat’. Even so Baldwin’s government still clung to the idea of trying to find ways of reaching some sort of agreement with Nazi Germany. Early 1937, Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden informed ministerial colleagues that the prospects for a general settlement with Germany were ‘very small’. Yet ministers felt that the best way forward was to follow a policy based on conciliation and compromise. Britain was clearly appeasing Germany from a position of weakness, rather than strength. Before 1930 Hitler perceived as ‘a ranting fool’ – Observer newspaper Even after the Night of the Long Knives massacre, The Times and most other newspapers of the time came to the conclusion that ‘during the next few years there is more reason to be afraid for Germany than afraid of Germany’. Only the Manchester Guardian was consistently hostile. When Germany was reasonably weak militarily (1933-1935) British government was unable to decide what to make of Hitler. By time Cabinet came to terms with idea that Nazi Germany was a serious threat to European security, that Hitler was aiming to make Germany the dominant power in Europe, there was little Britain could do. Unreliable Allies In 1920 the Republican candidate won the presidential election and promised America a ‘return to normalcy’. This meant not getting involved in European affairs. USA followed a foreign policy = Isolationism. In a private letter to his sister, Chamberlain wrote ‘You can count on the Americans for nothing but words’ Although America governments supported measures that promoted disarmament or the renunciation of war, for the next twenty years, the USA remained largely isolated from European affairs and did not commit itself to any alliances. Great Depression heightened US withdrawal. In 1935 US government passed the Neutrality Act which was designed to keep America out of a possible European war by banning the sale of armaments to belligerents. Act was subsequently extended to include civil wars, and to ban loans to belligerents. Clear message = there should be no expectation of help from the USA By early 1930’s French society was deeply divided between left and rightwing views. Successive governments failed to win support for an interventionist approach. According to Anthony Adamthwaite ‘If rulers and ruled had possessed the courage to say merde to Hitler before 1939 the story would have a different ending’ France had its own problems. In 1934, street rioting had brought down the government. France was politically divided and no short-term leader would commit France to any warlike moves against Germany. French military thinking was increasingly focussed on defensive strategies. France had a ‘Maginot Mentality’. The Maginot Line was a huge network of fortifications along the French-German border, most of it underground so as to avoid Fre3nch soldiers ever having to face the horrors of trench warfare again. This line of defences not only absorbed most of France’s military spending, it also created a static, defensive mentality. Many historians believe this lulled France into a false sense of security. By the late 1930’s Germany, Italy and Japan were allied to together but Britain had no allies apart from the Empire – this was a concern. 1931 Dominion countries had achieved complete independence from Britain in foreign affairs. Meant they would be free to decide whether they wanted to support Britain in any future war At 1937 Imperial Prime Ministers Conference, Prime Ministers of Canada, Australia and South Africa made it clear they favoured a policy of appeasement and they would not necessarily support Britain if it went to war. Stanley Baldwin resigned at the beginning of the Conference. It is likely that Chamberlain was influenced by these views. Military Weakness Britain had disarmed hugely at the end the Great War. Out of 130,000 serving aircraft at the end of the war only 120 were still in use three years later. Britain had adopted the ’10 year rule’. Belief was that any possible threat to Britain would be easily spotted and Britain would have plenty of time to get ready! Arrival of fascist dictatorships in the 1930’s took British military planners by surprise. Heads of Britain’s armed forces – the Chiefs of Staff – consistently warned Chamberlain that Britain was too weak to fight. Same time, Hitler’s propaganda encouraged Britain and France to believe Nazi forces were stronger than they were. Nazi film of soldiers marching into the Rhineland hid the fact that the soldiers were raw conscripts barely able to march in a straight line. Nazi tanks shown at rallies were often cardboard outlines placed over ordinary cars. The fighter planes and radar that saved Britain from defeat in 1940 were still at development stage in the late 1930s. Britain needed time to rearm. Appeasement was a way of gaining this time! Concern over the Empire British Empire was huge – ‘the sun never sets on the British Empire’ ¼ of the world’s population was under British rule. It was the wealth and power that came with the Empire that made Britain into a world power. Defence of the Empire was a no.1 concern for Britain. Government department that advised on Empire matters was called the ‘Committee of Imperial Defence’. As early as 1934 the C.I.D had warned that the government could not fight a war on three fronts. If Britain became involved in a war in Europe, would Japan start to nibble at the Far East and would Mussolini target the Middle East? The route through the Suez Canal was vital to Britain’s global communications. Close to the Suez Canal was Palestine. Mussolini was already stirring up an Arab revolt in Palestine that was tying down over 100,000 British troops. The British army was overstretched. Another concern was Empire unity. At an Empire Conference in 1937 the South African Prime Minister, Herzog, had said that if Britain became involved in a war with Germany, South Africa would not feel it had to help. Collective Security did not appear to work Although vast majority of people wanted the League of Nations to work, it did not seem able to provide solutions to problems when they arose. League’s weaknesses had been exposed i.e. Japanese invasion of Manchuria, had failed to achieve international disarmament, Italian invasion of Abyssinia. After 1936, it was clear that the League of Nations was not likely to provide a solution to international problems. Who’s Who – The Appeasers Lord Lothian: Leading Liberal in the House of Lords. Advocate of appeasement until 1939. Believed that personal contact with leading Nazis would lead to greater understanding and defuse the international situation. Often presented Hitler’s views in a very favourable light in the British press. Lord Halifax: Appointed Foreign Secretary in Feb 1938 when Eden resigned. Had strong anti-communist views and told Hitler he approved of the way the Nazis were dealing with communists in Germany. Henry ‘Chips’ Channon: American by birth, Channon was a junior Minister in Chamberlain’s government in 1938. Committed supporter of General Franco and favoured appeasement, partly because he hoped Hitler might be persuaded to attack the Soviet Union. Samuel Hoare (Lord Templewood): Hoare was Foreign Secretary in 1935 until he was forced to resign when news of proposed Hoare-Laval Pact was leaked. His willingness to appease Mussolini was rejected by the rest of the Cabinet. His support for appeasement appealed to Chamberlain, who brought him back into the government. Who’s Who – The Anti-appeasers Winston Churchill: Backbench Conservative MP from 1929-1940, Churchill was a leading advocate of rearmament and an outspoken critic of appeasement. He described the Munich agreement as ‘the blackest day page in British history’. Anthony Eden & the ‘Glamour Boys’: Eden resigned from the post of Foreign Secretary in Feb 1938 because he could no longer accept Chamberlain’s policy of appeasement. A group of about 25 MPs supported Eden, including Harold Macmillan. Sir Robert (Bob) Boothby: Conservative MP who joined Churchill and Leo Amery in demanding an increase in defence spending. From 1933 onwards, he was outspoken about Hitler and the threat that he posed. Duff Cooper: Secretary of State for War 1935-1937 and then First Lord of the Admiralty in Chamberlain’s government until he resigned in protest at the Munich agreement.