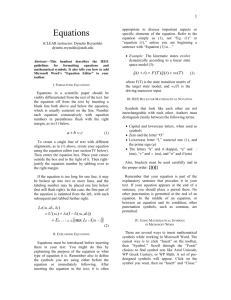

a Word document containing an equation

advertisement

The Microsoft Equation Editor I had not used the Microsoft Equation Editor until I started preparing for this class. It turns out to be fairly straightforward. The Equation Editor is not automatically installed when Word is installed. To find out if the Equation Editor is installed on the machine you are using and to install it if it isn’t, double click in the center of the following equation: b x x3 f (b) f (a) dx 4 x 2x3 a x 4 3x x 4 If the equation editor is installed, it should start. If it is not installed, the installation should begin. If you installed Word from a CD, you will need the CD to install the equation editor. The Equation Editor treats equations and other mathematical expressions as objects similar to clip art. To create a new equation, select “object” from the “Insert” menu and select “Microsoft Equation 3.0” from the list of possible objects. (Microsoft Equation 3.0 won’t be on the list if the equation editor has not been installed.) Equation Editor basics (This discussion is taken from Equation Editor “Help”.) Using Equation Editor, you can build complex equations by picking symbols from a toolbar and typing variables and numbers. As you build an equation, Equation Editor automatically adjusts font sizes, spacing, and formatting in keeping with mathematical typesetting conventions. You can also adjust formatting as you work and redefine the automatic styles. Easy-to-Use Toolbar Symbols and Templates The top row of the Equation Editor toolbar has buttons for inserting more than 150 mathematical symbols, many of which are not available in the standard Symbol font. To insert a symbol in an equation, click a button on the top row of the toolbar, and then click the specific symbol from the palette that appears under the button. The bottom row of the Equation Editor toolbar has buttons for inserting templates or frameworks that contain such symbols as fractions, radicals, summations, integrals, products, matrices, and various fences or matching pairs of symbols such as brackets and braces. Many templates contain slots — spaces into which you type text and insert symbols. There are about 120 templates, grouped on palettes. You can nest templates — insert templates in the slots of other templates — to build complex hierarchical formulas. For example, to create a fraction, you select a fraction template from the list of “Fraction and radical templates” on the toolbar. The template consists of a bar with slots above and below the bar for the numerator and denominator. You type the numerator in the upper slot (obviously) and the denominator in the lower. The numerator and denominator can contain fractions (as in the example). Selecting items with a mouse can be slow. I have discovered the following shortcuts. There are probably others. (Let me know if you find some.) CTRL+H give a superscript (high) CTRL+L gives a subscript (low) CTRL+J gives both a superscript and a subscript (joint) CTRL+F gives a fraction WARNING: If you have unfilled slots, you may get an error message when you try to save the document. If that happens, try to find the unfilled slots and eliminate them. If you can’t find the unfilled slot or you still can’t save the document, try copying and saving pieces of the document. (Of course, it is always a good idea to regularly save any document you are working on.) You can place mathematical expressions in the line of text. For example: Let f ( x) x 4 3x 3 4 x 2 3 . Find the roots of the equation f ( x) 0 . Note that each of the two equations is a separate object. As with clip art, you can change the size of an expression by dragging a corner. b f (b) f (a ) a x x3 3 x 2 x 4 x 4 3x x 4 dx One last example: You can create a binomial coefficient by selecting a parentheses template and then inserting the appropriate vector template. Filling the slots with the desired integers gives 12 66 . 2