Social Liberalism

advertisement

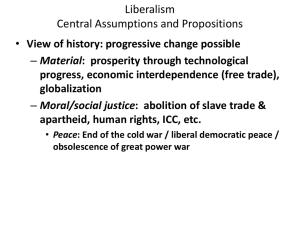

CONTENDING LIBERALISMS James L. Richardson Part I This chapter offers an interpretation of the normative tensions within liberalism. First, drawing attention to issues raised by the definition of liberalism, it supports the view that it involves a commitment to a plurality of political values, not the pursuit of one supreme value such as freedom. It sees the history of contending elitist and radical liberalisms as falling into three partially overlapping phases: the first over equal political rights (elitism versus democracy); the second over the economic and social implications of liberal values ("classical" versus "social" liberalism); and most recently, over the extension of liberal principles to those who are especially disadvantaged for a variety of reasons ("inclusive" liberalism). THE CONCEPT OF LIBERALISM Liberalism resists sharp definition: "it is hardly less a habit of mind than a body of doctrine," or "often a matter of broad cultural allegiance and not of politics at all" (Laski 1936, 15; Dunn 1993, 30). Yet most historians are in broad agreement in identifying a cluster of values that have characterized liberalism since its inception. John Dunn sums them up as "political rationalism, hostility to autocracy, cultural distaste for conservatism and for tradition in general, tolerance, and . . . individualism" (Dunn 1993, 33). For John Gray the distinctive liberal values are individualism, egalitarianism, universalism, and meliorism (Gray 1986, x). And Anthony Arblaster lists them as freedom; tolerance; privacy; constitutionalism and the rule of law; reason, science, and progress; and—implicitly—property. But he also maintains that individualism is the "metaphysical and ontological core" (Arblaster 1984, 15, 55-91). The characteristic liberal values can be contrasted with those of other traditions. Conservatism, for example, places high value on order, authority, community, and established institutions and tends to favor stability over change; it is comfortable with hierarchy and inequality, hostile or sceptical toward radical reform, and quick to condemn the perceived excesses of individualism or egalitarianism. Socialism, and especially social democratic thought as it developed in Western Europe, shares many liberal values but gives greater weight to equality alongside freedom and to community against individualism. Historically, the differences between liberals and socialists were less over values than over the means for realizing them. Viewed historically, liberalism is first and foremost normative: a body of ideas about social and political values, the principles that should govern political life, the grounds for political legitimacy. The cluster of values now identified with liberalism came into being over a long period. Not all commentators are satisfied with the concept of liberalism as a cluster of values; it lacks sharpness and does not indicate which value has priority. For many there is a clear answer: "liberty ... is the highest political end" (Acton, quoted in Arblaster 1984, 56). For Alan Ryan the most plausible brief definition is "the belief that the freedom of the individual is the highest political value, and that institutions and practices are to be judged by their success in promoting it" (Ryan 1993, 292-293). He acknowledges that this presents difficulties: there are serious disagreements over the meaning of freedom, and indeed it is an "essentially contested concept." This definition presents a number of other difficulties. For the utilitarians, for example, the supreme value is not freedom but the greatest happiness of the greatest number. And there are other candidates for the defining concept. The classic liberal manifestos were multivalued: liberty, equality, and fraternity; life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. 1 Like other modern political traditions, liberalism consists in a sequence of debates, literal or figurative—the spelling out of contending positions with some reference to what went before. The present interpretation—accentuating one of the subthemes in Arblaster (1984) and in Hartz (1955)—is that the central tension is between two liberalisms, elitist and radical. The former may also be termed, in differing contexts, the liberalism of privilege or liberalism from above; the latter egalitarian, social, or inclusive liberalism or liberalism from below. For some historians, liberalism does not emerge until the eighteenth century; more precisely, their narratives begin with the "Glorious Revolution" of 1688 and the publication in 1690 of John Locke's Two Treatises on Civil Government (see, for example, de Ruggiero 1927/1959; Bramsted and Melhuish 1978). In Locke, as Gray expresses it, "the central elements of the liberal outlook crystallized for the first time into a coherent intellectual tradition expressed in a powerful, if often divided and conflictual, political movement" (1986, 11). It has been argued convincingly, however, that political movements propounding liberal values first appeared in the mid-seventeenth century, when characteristic liberal themes and debates were articulated in the English Revolution (Laski 1936, 104-118; Arblaster 1984, 146-161; Patterson 1997). This narrative therefore begins with these debates. It is necessarily selective, highlighting certain developments and debates in order to bring out what is familiar and what is distinctive in contemporary liberal doctrine. Seventeenth-Century England The English Civil War and the Commonwealth during the two decades 1640-1660 provided the setting for the first open political debate in modern Europe. Fifteen thousand pamphlets appeared during these decades (Arblaster 1984, 153), as did the main political works of Hobbes, Harrington, and Filmer. Historians dispute whether there was a genuine revolution, but irrespective of that issue, it was not a revolution (or movement) in the name of a new political philosophy. Rather, the ferment of ideas, the debate over political fundamentals, was occasioned by the breakdown of political order, and the Commonwealth was an improvisation. Following Cromwell's death, no ideological rallying point stood in the way of the Restoration. While there was no fully developed liberal position in these debates, there was an eloquent assertion of certain liberal values and, more important, the clearest possible expression of the tension between the two poles of liberalism. At the heart of the seventeenth-century arguments, writes Arblaster, lies a hard issue which is central to liberalism: the question of the relations between freedom and property. It was increasingly asserted and accepted that a man may do what he will with his own . . . "every free subject of this realm hath a fundamental property in his goods and a fundamental liberty of his person." But who counted as a free subject? This was the subject of much dispute, yet in the end it was the property-owners who triumphed. It was accepted that they had the right, not only to do as they pleased with "their own," but also to control the state itself. (1984, 150) These issues were argued out in the debates between the Levelers and the army leaders (the "Grandees") at Putney in 1647. Levellers are seen as genuine radicals, seeking to uphold the rights of all—that is to say, all English men. Against this, the army leaders defended the traditional principle that the vote was for those with a stake in the country, in other words, for owners of property. The army leaders prevailed, but the debate served to highlight the gulf between the claims of equal rights and the actual principles of English parliamentary representation, which were to survive for two centuries. Locke If the Levelers were the first to expose fundamental issues that would divide liberals, John Locke wrote what came to be regarded as the first great liberal texts: The Second Treatise of Government and A Letter Concerning Toleration. Initially, his work was seen as too radical to be welcome to 2 England's new rulers after 1688—too forthright a defense of the right of revolution against an oppressive monarchy. Much of what became characteristic of liberal thought is not yet present in Locke's work or no more than hinted at—for example, constitutionalism and the separation of powers—and the idea of limited government is discussed only by way of example, admittedly a crucial one: property. What he does offer is the classic formulation of the liberal view of the conditions of political legitimacy. We may note some of his central themes. First, individualism: Locke begins with individuals in the state of nature, enjoying freedom and equality. Although he does not develop a systematic account of natural rights, they provide the foundation, and the individual remains his point of reference, not the community or its institutions, for example. Second, consent: the idea of the social contract is a metaphor, not a historical account of when or how people give their consent to live under a particular government. The idea that the right to rule depends on consent—that authority derives from below, not from above—has been one of the most powerful political ideas since that time, with revolutionary implications for traditional hierarchical societies. Third, and closely related, are the ideas of the rule of law and of government as trustee. The latter was to influence liberal theory on colonial administration, but for Locke it served to underline governments' obligation to act in the interests of the people, not the rulers. Governments are dissolved when they act contrary to their trust—when they "invade the Property of the Subject" or make themselves "arbitrary Disposers of the Lives, Liberties or Fortunes of the People" (Locke 1690/1965, 460). Arbitrary power is illegitimate; rulers are obliged to respect the laws enacted by the legislature. A fourth theme was the significance of property: "The great and chief end, therefore, of Men uniting into Commonwealths, and putting themselves under Government, is the Preservation of their Property" (1690/1965, 395). It was this ringing affirmation not the ambiguities of his definition of property, that explain Locke's appeal to the propertied classes. It offered reassurance, balancing his political radicalism—"a charter for political revolution which would be in no way socially subversive" (Dunn 1969a, 50). Finally, on toleration, Locke offered a variety of arguments for the individual's right and duty to seek salvation in accordance with his own religious beliefs, and the inadmissibility as well as ineffectiveness of the state's seeking to impose a religion against the convictions of those who dissented. Today his exceptions arouse adverse comment; he denied toleration to atheists for their amorality and to Catholics, since their allegiance to the Pope took precedence over their loyalty to the government. But his central argument remains a powerful statement of one of the core liberal values (Dunn 1984, 22-27, 57-59). The United States: The Formative Period Hartz offers an explanation of U.S. political culture—'American exceptionalism"—in terms of the fit between individualist liberalism and America's unique historical experience and social structure. In Europe liberalism emerged in the context of a highly stratified, hierarchical society. The early liberal elites sought to overcome political absolutism and the closed aristocratic elites that supported it, but without risk to property or opening the way to rule by the "mob." In the United States, however, landed property was widely diffused, and opportunities for individual advancement were sufficient to remove the sense of threat from below that was so strong in Europe. In the American setting an individualist philosophy (Locke) could win acceptance at all levels of society. As Hartz expresses it, with reference to de Tocqueville: In a society evolving along the American pattern of the Jeffersonian and Jacksonian eras, where the aristocracies, peasantries, and proletariats of Europe are missing, where virtually everyone, including the nascent industrial worker, has the mentality of an independent entrepreneur, two national impulses are bound to make themselves felt: the impulse toward democracy and the impulse toward 3 capitalism. The mass of the people, in other words, are bound to be capitalistic, and capitalism, with its spirit disseminated widely, is bound to be democratic. (1955, 89) In practice, the individual American states moved at different times from a franchise based on landed property, along English lines, through a broadening of the property qualifications and their replacement by a taxpayer qualification, to eventual manhood suffrage, such that by the time of the very limited British electoral reform of 1832, most American states had white male suffrage or at least a taxpayer franchise. This democratizing process went along with the opening up of the country to the west, offering opportunities to those willing to pursue them. Jacksonian democracy in the 1830s gave strong expression to the individualist ethos and supported a pragmatic laissez-faire approach to the economy, its particular targets being corporations and financial institutions granted monopolistic privileges by the state. In the absence of the kind of social tensions that were so acute in Europe, there was no ideological conflict and no impetus to political theorizing (Hartz 1955, 141). It was perhaps the easy triumph of American democracy in these circumstances that consolidated the individualist political culture. France: Enlightenment/ Revolution/ and Restoration The liberal values expressed complacently and unreflectively in eighteenth-century England found fuller and sharper expression in the French Enlightenment, where the defense of toleration and freedom of speech incurred the deep hostility of the Church and risked imprisonment or exile by the state, as Voltaire's experience made clear. In this setting the enthusiasm for science and education, the early expression of the basic ideas of utilitarianism, and above all, the subjection of all beliefs to the test of reason had the effect of gradually undermining the legitimacy of the absolutist monarchy. The Enlightenment thinkers did not put forward a program of political reform, but their praise for the English system meant that it was the example of constitutional monarchy that came to hand when absolutist rule collapsed in 1789. The Enlightenment thinkers by and large shared the social conservatism of the English rulers; the existing deep social divisions were taken as given. There were the same expressions of concern about the mob, and Diderot was representative in assuming that citizenship rights should be tied to property (Arblaster 1984, 189-191). The constitutional monarchy, needless to say, could not survive the turmoil of the French Revolution. As the moderate Girondins gave way to the radical Jacobins, followed by the Terror and the Dictatorship, the initial liberal enthusiasm for the revolution gave way to dismay, both in France and elsewhere. The Declaration of the Rights of Man (August 1789) had invoked both the classical liberal freedoms and equal rights: "Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions can only be based on common utility." But if this was open to a democratic interpretation, the course of the revolution confirmed all the liberals' worst fears of democracy— rule by the mob. For several generations most European liberals would reject democracy, and the egalitarian values that had surfaced briefly in 1789 were firmly subordinated to the values of freedom and constitutionalism. It is occasionally questioned whether utilitarianism should be included within liberalism. As Arblaster notes, there is potential conflict between the liberal principle of freedom and the utilitarian principle of happiness or pleasure (1984, 350). This may be regarded, however, as one of those tensions within liberalism normally left unexamined—not surprisingly, since utilitarianism is usually seen as the dominant ethical theory in twentieth-century liberal societies (Rawls 1972, viiviii), providing the normative rationale for public policies and, in particular, for welfare economics. Bentham and his followers affirmed most of the Enlightenment themes—reason, science, education, the rejection of arbitrary government—and offered the principle of utility in place of the appeal to tradition or authority. Above all, the utilitarians shared the liberals' individualism—in their image of society as consisting of self-interested individuals and in making the individual the point of reference for their normative thinking. 4 The fear of democracy was widely shared in early-nineteenth-century England, but even so, the early utilitarian thinkers drew the logical—radical—conclusion from their principle of the greatest happiness of the greatest number. Bentham went so far as to endorse universal suffrage, and James Mill a franchise sufficiently wide to ensure all interests were represented (Plamenatz 1949, 82-84, 105-109). Only then could there be any assurance that governments would take the interests—the "happiness"—of the greatest number into account. Mill responded to conservative objections by arguing for broad-based education; an educated populace would respond to reasoned argument and would respect property. Such arguments wholly failed to persuade the political elite. Electoral reform proceeded very slowly through extensions of the property qualification for the vote, and universal suffrage came only in 1918. Rather surprisingly, it was a utilitarian of the next generation, John Stuart Mill writing in the 1860s, who expressed greater concerns over democracy. By then the elemental fear of the threat to property had given way to the liberal individualist's fear of the tyranny of the majority—the tyranny of conformism, the threat to intellectual and cultural freedom. Mill proposed electoral schemes for weighted voting intended to enhance the position of the educated, not the wealthy—a liberal compromise that failed to win support (Arblaster 1984, 277282). Nineteenth-century liberals, then, remained ambivalent toward democracy, even though the logic of equal rights, no less than utilitarianism, pointed in this direction. Radical liberals had given the initial impetus, but the liberal elite, primarily concerned with individual freedom and constitutionalism, remained a brake on its development. Part II SECOND PHASE: LAISSEZ-FAIRE VS. SOCIAL LIBERALISM The nineteenth century saw the emergence of a second major cleavage within liberalism, this time relating to political economy. Liberals retained a shared commitment to freedom and constitutionalism but divided over the implications of liberal values for organizing society under the conditions of industrialization, which, along with massive problems, created entirely new opportunities for realizing liberal rights and freedoms for the people as a whole. The cleavage was not articulated as one between elitism and egalitarianism but was readily recognized by contemporaries as such. It will be argued that there is normative continuity between the two overlapping phases. The central issue remained essentially the same: were liberal rights and freedoms to be genuinely extended to all? Political Economy Utilitarianism provided the political framework for the thinking of the early political economists, which in turn gave rise to laissez-faire economic policy (Coats 1971, 4-17). This was by no means a necessary consequence of utilitarianism. Initially, Bentham's thought prompted wide-ranging legislative and administrative reforms, and by midcentury John Stuart Mill foreshadowed the later development of utilitarian thought in favor of the welfare state. But for more than a generation, starting in the 1830s, utilitarianism was enlisted in support of laissez-faire, to the point of legitimizing the excesses and urban misery of the early Industrial Revolution. Adam Smith's sanguine expectation of the general benefits of the "hidden hand" was now overshadowed by Thomas Malthus's doctrine of population expanding to the limits of subsistence and David Ricardo's assumption of conflicting class interests. Nonetheless, faith in laissez-taire remained unshaken. Whatever ills might be apparent, government intervention could not ameliorate them. "There is no one to blame for this; it is the result of Nature's simplest laws!" Some historians deny that the classical economists were committed to laissez-faire; it is claimed, for example, that their recommendations "were on the whole cautious and reasonable" (Coats 1971, 17). It is true that individual economists were prepared to support state initiatives in a 5 number of areas such as public works and education. Moreover, the classical economists were surprisingly pragmatic on free trade, so much an article of faith for the contemporary economics profession (Coats 1971, 28-29). Ricardo, for example, implied that the abolition of the grain tariff would not have the general benefits proclaimed by Richard Cobden and the Anti-Corn Law League. Most of them accepted the need to regulate children's hours of work in factories, and they were not uniformly opposed to factory legislation generally. Nonetheless, allowing that classical economists were not "dogmatic exponents of laissez-faire," it was the simple, dogmatic version of their views that entered into political discourse. The most indefatigable defender of laissez-faire was the Economist, founded in 1843 by James Wilson. It may not be correct, however, to attribute the oversimplification of laissez-faire entirely to popularizers and politicians. The economists themselves were not free from simplification. This was facilitated by the style of reasoning introduced by Ricardo, which profoundly influenced the development of the discipline. In a world of complexity and contingency, the Ricardian style of reasoning encouraged policymakers to posit simple, uniform relationships. Joseph Schumpeter addresses the issue at some length: The comprehensive vision of the universal interdependence of all the elements of the economic system . . . probably never cost Ricardo as much as an hour's sleep. His interest was in the clear-cut result of direct practical significance. In order to get this he cut that general system to pieces, bundled up as large parts of it as possible, and put them in cold storage—so that as many things as possible should be frozen and "given." He then piled one simplifying assumption upon another until ... he was left with only a few aggregative variables between which, given these assumptions, he set up simple one-way relations so that, in the end, the desired results emerged almost as tautologies. (Schumpeter 1954, 472-473) Schumpeter terms this the "Ricardian vice," and John Maynard Keynes comments that "the almost total obliteration of Malthus's line of approach and the complete domination of Ricardo's for a period of a hundred years has been a disaster for the progress of economics" (Keynes 1956, 33). Ricardian economics, then, encouraged the oversimplification of policy issues; a later chapter will suggest that Schumpeter and Keynes are correct in seeing this as a recurring problem. Along with this fundamental analytical weakness, laissez-faire economics illustrates a mode of normative one-sidedness that became a recurring feature in liberal thought. Until then, economic freedom had not been the overriding value promoted by liberalism but had been balanced by the idea of moral equality—whether in the form of natural/ universal rights; Kant's imperative that every person be treated as an end, not a means; Adam Smith's assumption that economic development should benefit all levels of society; or the utilitarian norm of the greatest happiness of the greatest number. In laissez-faire economics the egalitarian commitment disappears entirely. The principle that the state not intervene in the economy—and indeed refrain from any social initiative—is elevated into a categorical imperative. The currently existing distribution of property rights (and the ensuing unequal chances) is treated as sacrosanct; the realization of individual values is entirely subordinated to it. It is not surprising that the extreme conditions of early industrializing England and the extreme doctrine of laissez-faire provoked extreme reactions. For more than a century, though not initially in England itself, the most important of these was socialism. Normatively, it elevated equality alongside or even above freedom; analytically, it replaced individualism with an emphasis on social class. And its approach to policy was the opposite of the liberal's minimal state, although how great a role to accord the state varied. The initial English reaction against laissez-faire, however, was led by conservatives, drawing occasionally on European anti-Enlightenment thought but more on a benign reading of the English conservative tradition as one committed to social balance and the good of the community as a whole (Disraeli voiced the concern that England had been split into "two nations"). It was a Conservative, Shaftesbury, who led the movement for factory legislation against what was depicted as the ruthless class interest of the manufacturers. Such critics had no hesitation in identifying laissez-faire liberalism as elitist. There was also a strong cultural reaction. Dickens did not limit himself to depicting the evils of London's poverty but savagely satirized the 6 rationalizations of political economy. Carlyle denounced the evils of mammonism, and Matthew Arnold lamented liberalism's cultural poverty (de Ruggiero 1927/1969, 138-139; Arblaster 1984, 246-247, 252, 274-275). Social Liberalism The reaction against laissez-faire prompted a new direction in liberal thought in Britain and Germany in the later nineteenth century and, to a much lesser extent, in France and the United States. This amounted to a major rethinking of liberalism in the light of the conservative and socialist critiques of laissez-faire. Accepting part of the critique, the social liberals (the English "new liberals") maintained that this did not mean an abandonment of liberalism but rather its reformulation. Under the conditions of industrial society the insistence on the minimal state and the view that trade unions obstructed economic progress no longer promoted liberal values but became obstacles to their realization. In Britain, where John Stuart Mill had initiated the debate, T. H. Green in the 1880s and L. T. Hobhouse in the early twentieth century undertook a more thoroughgoing rethinking of liberal philosophy. Green broke not only with utilitarianism but with the whole tradition equating liberalism with "negative freedom"—freedom from control by the state. Instead he drew on the Hegelian idea of "positive freedom"— in Green's words "a positive power or capacity of doing or enjoying, [not] at the cost of a loss of freedom to others [but] something that we do or enjoy in common with others." The ideal of true freedom is "the maximum of power for all members of society to make the best of themselves" (Bramsted and Melhuish 1978, 652-653). Central to Green's thought is not only positive freedom but equality: the equal claims of all members of society to realize their potential. Thus reinterpreted, individual freedom remains a core liberal value. A familiar liberal norm such as freedom of contract is not an end in itself but a means to an end, and the essential criterion for judging social legislation is whether it is needed to provide the preconditions for the realization of positive freedom for the less advantaged members of society (Bramsted and Melhuish 1978, 653-656). Hobhouse presents the history of liberalism as advancing toward the more comprehensive theory of his time, which looks to the positive realization of individual potential in the context of industrial society (Hobhouse 1911/1994; Meadowcroft 1994). Like Green, he sees this as requiring a far more positive role for the state, as a means to this end, than the classical liberals—preoccupied with the struggle against absolutism, aristocratic privilege and anachronistic economic regulations—had allowed. Also like Green, he emphasizes equality, indeed equality of opportunity (1911/1994, 15) and, whether consciously or not, he echoes a Kantian theme in contending that "liberty . . . rests not on the claim of A to be let alone by B, but in the duty of B to treat A as a rational being" (1911/1994, 59). Normatively, Hobhouse espouses liberal individualism but seeks to balance it with a doctrine of what the individual owes to the community. Empirically, he breaks more decisively with an individualist conception of society, replacing it with an organic theory (1911/1994, 59-66; Meadowcroft 1994, xi, xvii-xx). Like others at the time, Hobhouse was well aware there was a problem of distinguishing liberalism, thus redefined, from socialism in its local (Fabian, nonMarxist, eclectic) version—just as, from a more extreme socialist perspective, the Fabians were difficult to distinguish from liberals. The Great Depression Despite the efforts of policymakers in the 1920s, it proved impossible to restore the liberal international economic order that had been shattered by World War I. By the 1930s liberalism was rejected in central and eastern Europe in favor of totalitarian or authoritarian regimes. In Britain and France, as political conflict became polarized in different ways between left and right, liberalism was discredited, even though the political culture remained essentially liberal-democratic. Only in the United States, despite the unprecedented shock of the Depression, was there no ideological 7 conflict and no threat to the liberal order. We may note two significant liberal responses to the Depression: that of John Maynard Keynes in Britain and the New Deal in the United States. Keynes identified with liberalism and the Liberal Party, not as a political theorist but through his personal and political commitments. Hostile to diehard conservatism, he had some sympathy with the Labour Party but not with socialism or class conflict. "He could never take [Marxism] seriously as a science. But he did take it seriously as a sickness of the soul" (Skidelsky 1992, 517). By contrast, he drew much of his inspiration from the classical political economists. He exemplified the core liberal values and cast of mind, placing the highest value on individual cultural pursuits, and shared the liberal confidence in science and, ultimately, progress (Arblaster 1984, 292-295; Skidelsky 1992, 405-430). Sympathizing with the young generation's rejection of capitalism but scorning their marxist solution, he held that the system could be salvaged, but only through a fundamental rethinking of its operation. His anger and polemics were directed against the crippling economic orthodoxies of the day—their rationalizations, their acquiescence in mass unemployment, their blindness to new issues that challenged their models, their refusal to struggle for new models adequate to new situations. From his struggles emerged his model of the macroeconomy, his proposals for demand management by the state, and later, his ideas for reforming the international financial system. The New Deal was not the product of a single doctrine or theory but consisted rather in a sequence of pragmatic expedients—"bold, persistent experimentation"—that reflected Roosevelt's temperament and found a positive response from the electorate. If the economic policies eventually came to appear Keynesian, this was due mainly to the logic of events but also to openness to new ideas. But there was no revision of liberal theory in favor of greater state initiative. Many of the New Deal's policies were relatively old, in European terms, yet in the absence of an effective socialist movement they appeared radical in American terms and, accordingly, were assailed from the right. Because American political culture remained individualist (Lockean), there was good reason to avoid formulating a social-liberal doctrine vulnerable to attack within that culture. But this would leave social-liberal measures highly exposed to subsequent critique. Embedded Liberalism For Western societies the decades after 1945 were a time of unprecedented economic growth, its benefits distributed relatively equitably, and of politically stable democracy, except for a handful of southern European countries. The period is often identified with the welfare state. The question is whether, when economies are so much subject to state initiative and regulation and the goals of politics are identified with welfare rather than freedom, the societies in question are rightly termed liberal. Those who followed Green and Hobhouse had no difficulty in answering affirmatively: the expanded economic and social role of the state was a necessary means in modern industrial society to enable individuals to achieve freedom—to realize their potential. Ruggie, following Karl Polanyi, makes a related point: an unregulated market economy would create a degree of deprivation and social disruption that would prove intolerable. Governmental regulation of the market is therefore necessary in the interests of social stability and balance (Ruggie 1982, 393-398). The logic of the market does not completely dominate society, but the economy is "embedded" within a social and political order that limits its potential for unraveling social bonds. German thinking on the socialmarket economy followed similar lines. The differences between classical and social liberalism are partly over values but even more over institutional means: how can liberal values best be realized in contemporary society? Classical liberalism does not constitute the whole of the tradition but refers to a particular historical phase. There is no reason to regard any one conception of political economy as defining liberalism for all time—Adam Smith's conception, for example, any more than those of Alfred Marshall or Keynes. Social liberalism is as much part of the liberal discourse as its rival; the attempt to exclude it is essentially a political act seeking to exploit a traditional association of ideas. It is also an attempt to narrow down liberal values, marginalizing equal rights, redefining liberalism so that "economic 8 freedom," understood in a particular way, becomes the supreme, defining value. This view could not survive a reading of the classical liberal texts but amounts to a distortion and narrowing of the history of liberal thought. The Neoliberal Ascendancy In the European context the resurgence of classical liberal thinking in the 1970s and its subsequent dominance of public discourse came as an astonishing, barely comprehensible turning back the clock—a return to laissez-faire, as it was often perceived. In the first instance it was a rejection of Keynesian economics, but viewed more broadly, it amounted to a revival of the political-economic thinking that preceded Green and Hobhouse, with its determination to minimize the economic role of the state—the philosophy of "small government." Indeed, contemporary neoliberal ideology, as it shall be termed, seeks to go further: it amounts to an attempt, far more thoroughgoing than that of its nineteenth-century predecessor, to subordinate the state to the market and to transform the political culture to this end. Its effect on political practice has been varied, but even though it has not always been successful in reducing the level of state expenditure, the neoliberal offensive has succeeded in eroding the legitimacy of the welfare state and, more broadly, the public sector and in impoverishing publicly funded institutions, especially those such as universities and libraries for which there is no mass electoral lobby. Deregulation and privatization have been the leitmotifs. In Thatcher's Britain, the extreme case, social provision by the state was pared back and the public sector extensively privatized, but equally striking were the new centralization of government, the lack of accountability of services formerly publicly provided, and the elimination of many of the institutions and traditions of English conservatism (Gray 1997, 1-10, 97-155). In the United States, on the other hand, the revival of an earlier liberalism aroused no sense of shock but seemed quite normal. Although many American economists had become Keynesian and certain welfare programs had achieved wide acceptance, public rhetoric had never endorsed social liberalism or the welfare state. Whereas the sudden canonization of Friedrich Hayek in Britain required something like a paradigm shift, Milton Friedman was able to invoke familiar themes in the American public discourse that had survived in the pragmatic eclecticism of the New Deal and the Great Society. In Britain there was indeed a change in the political and intellectual climate in the 1970s, but it did not amount to a paradigm shift. What Hayek offered was not a new paradigm but essentially the reaffirmation of an old one, albeit in the unfamiliar idiom of the "Austrian school." He offered an appealing image of the spontaneous order created by the market, coordinating the myriad individual decisions in the economy in a way that was beyond the knowledge or capacity of governments; not only central planning but any effective regulation of the economy was impossible. He was at pains to demolish as meaningless the concept of social or distributive justice, in the name of which governments restricted individual freedom (Hayek 1960, 1976; de Crespigny 1976). Hayek's ideas caught on in Britain, which was experiencing serious economic problems in the 1970s, a good deal earlier than elsewhere in Europe. Hayek was the leading figure among the initially small number of free market economists and publicists in the early postwar years (Cockett 1994). His many political writings offered an uncompromising reaffirmation of the antistatist tradition, entirely unresponsive to the concerns of embedded liberalism. The Road to Serfdom (1944) ranks as one of the classic liberal statements against totalitarianism, but it has not aged well. Its claim that any move beyond the minimal state placed a society on the slippery slope to totalitarianism lacked plausibility, neglecting as it did the liberal political culture in twentieth-century Britain and France. If Hayek provides the most wide-ranging case for neoliberalism, Milton Friedman is its most effective publicist—the new authority figure, displacing Keynes in the public discourse. Free to Choose (1980) written with Rose Friedman—the practical application of the principles advanced in Capitalism and Freedom (1962)—ranks among the most polemical of the liberal texts. Showing little awareness of the concerns of liberalism's critics, or for that matter historical scholarship, the 9 Friedmans are able to present nineteenth-century England as a golden age. Public health services, public education, consumer protection, and labor legislation are unable to achieve their goals and incapable of reform: salvation lies in a return to the minimal state (1980, 118-291). When all the institutions of the welfare state have been eliminated, any residual welfare concerns can be met through a negative income tax, though it is not explained why the majority of self-interested voters would agree to such generosity to the disadvantaged. The Friedmans do not engage with issues of liberal political theory, but they acknowledge the influence of "exciting work in the economic analysis of politics," that of public choice theorists such as Anthony Downs and James Buchanan (1980: 10). Public choice theory applies the economist's mode of analysis—the use of highly simplified, ahistorical, "parsimonious" models—to political processes and decisions. Political actors such as voters, politicians, and bureaucrats are viewed as "economic men," seeking to maximize their material interests, and occasionally other self-regarding, power-seeking interests. The ensuing simplification of politics complements and reinforces the simplification of social and economic issues and the neoliberal denigration of the state. Through thus buttressing neoliberalism, public choice may well be the most influential of the schools of contemporary political theory; it offers a ready-made, congenial political doctrine and contributes to the spread of the "economic discourse" in public affairs as well as to the devaluing of normative concerns and the cynicism toward politics and government that is readily evoked in most Western political cultures. Public choice may be included within liberalism, both for its association with liberal economics and its extreme analytical individualism. But it has little in common with liberal normative theory; in effect, it bypasses liberal political thought, presenting itself as empirical theory. Nonetheless, a narrow range of normative presuppositions, in particular a commitment to negative freedom, underpins its sceptical-to-hostile attitudes toward the state. 10