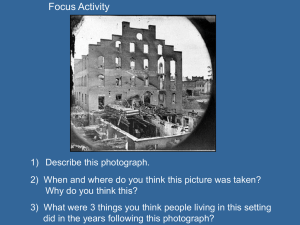

Post Civil War Reconciliation in the U

advertisement