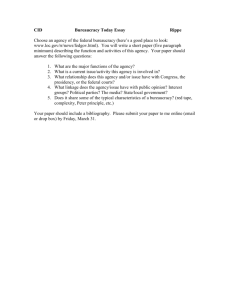

yagami-chalmers.doc - Virginia Review of Asian Studies

advertisement

29 CHALMERS JOHNSON AND THE ROLE OF THE JAPANESE BUREAUCRACY IN THE ECONOMY KAZUO YAGAMI SAVANNAH STATE UNIVERSITY Abstract: There is nothing more scrutinized than the Japanese bureaucracy in the analysis of finding causes of the trade friction between the United State and Japan. This paper attempts to see where such scrutiny stemmed from by analyzing the historical background for the birth and development of the Japanese bureaucracy and what roles the bureaucracy took in forming modern Japanese economy and establishing its astonishing successes and achievements. The paper also closely looks at the Japan bashers’ points of view, particularly one of the most well known Japan bashers, Chalmers Johnson’s: where his contentions come from and what is weakness and strength in his arguments. Probably there is nothing more scrutinized than the Japanese bureaucracy in the analysis of finding causes of the trade friction between the United States and Japan. Japan bashers show an accordance in their argument that Japan's economic success is a result of the orchestration by Japanese bureaucrats with their calculated effort to secure their power by bringing the public norm to the "supreme objective of making and keeping Japan economically and politically competitive at any cost. It is true that the orchestration took place-particularly, during the Meiji Restoration 1868 and the following Meiji Era (1868-1912), it was conducted in a vigorous manner, and today, the bureaucracy still remains as a core part of the Japanese political and economic systems, if less conspicuously than before. One ought to be careful, however, before he or she accepts the Japan bashers’ argument. The orchestration has been conducted by the bureaucrats in a far less selfish and less forceful manner than what the Japan bashers claim to be. It does not really take a scholarly eye or knowledge to discern that their arguments are based on distortion and inadequateness in analyzing the social and economic conditions of Japanese society. The purpose of this paper is to establish a proper understanding of the nature of the Japanese bureaucracy and its role in today’s Japanese economy by examining the historical background of the development of the bureaucratic system and the allegedly unfair practices of the Japanese bureaucracy. Japanese Bureaucracy 29 30 In order to establish a proper understanding about the Japanese bureaucracy, one needs to go into the modern Japanese history. The Japanese bureaucracy was established as a result of the transformation from the ruling class of the samurai during the Tokugawa period (1603-1868) into the administrative class in the Meiji Era. During this transformation, one of the most important decisions which determined the following course of the Japanese bureaucracy in the Modern Era was made. That was the separation between power and authority by adopting the governmental system of Imperial Germany (monarchic constitutionalism). According to the Bismarckian system, the prime Minster was responsible only to the king, not to a parliament, and also the king held the control of the army. It was purposely designed to give power first to Bismarck and then to the Prussian and Imperial bureaucracy. Under this system, the king kept authority but with no power attached. Actual power came to the bureaucracy. The Meiji leaders (bureaucrats) found this system preferable to the other models in the course of their modernization.1 There were two things needed to be dealt with in the early stage of modernization. One was how to subdue the growing criticism against their monopolistic power over state affairs. Most of the Meiji leaders were the former samurai from two feudal domains: Satsuma and Choshu, who were mainly responsible for the successful Meiji Restoration. The other was how to achieve an early revision of the unequal treaties which the imperial Western powers forced on Japan. Such revision required the Meiji leaders to demonstrate Japan's readiness and capability to achieve modernization. Under these circumstances, it was inevitable to develop a political system that would be appealing to the Western powers, which resulted in the birth of political parties and the establishment of a parliament (National Diet). With this development, there was an increasing demand from the party politicians for power sharing with the state bureaucrats. Subduing such a demand, however, was not necessarily formidable for the bureaucrats for the following three reasons. First, the state bureaucracy preceded the Meiji constitution, the Diet, and the formation of political parties by about five to twenty years, giving the bureaucrats advantageous background in dealing with the political situation. Second, in the process of industrialization, even though the political parties increased their power by gaining support from the zaibatsu (the financial cliques) and the other propertied interest groups, there was no grass root support for them due to bureaucratic control over the enlargement of the franchise. In 1890, only males who were over 25 years old and paid 15 yen or above as direct tax were given the right to vote, which was only 1.3 percent of Japan's population (39.9 million).2 Over the course of history, there had been some improvement. But the voting right was limited only to a small portion of the population until the 1946 new election law removed all the restrictions over the franchise, allowing all men and women who were twenty or above to vote. Third, there was the domination of one house of the Diet--the House of Peers--by the bureaucracy. It was the bureaucracy which could control the direct imperial appointment to the Peers for its retired members. These conditions made it possible for the bureaucrats to conduct successfully their modernization plan throughout the Meiji Era, the Taisho Era (1912-1925), and the early 30 31 Showa Era (1926-1989) until the arrival of world economic and political instability in the early 1930s and the following devastating World War II. They proved their capability in leading the nation. By the early 1900s, with the leadership of the bureaucrats, Japan had succeeded in revising the unequal treaties with the Western nations and established its status as one of the major powers in the world stage with its successful industrialization and militarization. The Second World War and its outcomes, however, had shattered such bureaucrats' success. They brought drastic changes in Japan's institutional structures, ending, under the guidance of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP), all the advantageous conditions the bureaucrats had in governing, except the unchanging cultural norms of Japanese society. For example, when the Emperor lost his divinity, they lost their special status as the officials of the Emperor (kan) who were not constrained by law. Under the new election law of 1946, they also lost their controlling power over the franchise. In an institutional fashion, they had to deal with something unprecedented--a truly democratized society, which was brought about literally overnight. The precipitate rise of power in political parties became inevitable. Furthermore, the public mood was understandably antigovernment. In short, in the beginning of the postwar era, the bureaucrats found themselves in quite a different ball game from that in the prewar era. Despite all these changes, however, the bureaucrats have managed to stay in power, achieving astonishing success in rebuilding Japan. How could this be possible? There are two things to be considered in order to answer this question. First, as Japan had faced in the aftermath of the Meiji Restoration, there was a strong sense of urgency for having an early recovery of the economic and political structures from the war destruction. Such urgency and the emerging communist threat from the Soviet Union forced SCAP's attempt for reforming the bureaucracy to fall short of anything drastic. SCAP reformed the Japanese bureaucracy only partially, purging only the war bureaucrats. The economic bureaucrats were left intact. Chalmers Johnson claims that the power of the economic bureaucrats was even enhanced when vacuum was created in the power structure by the elimination of the military and the transformation of the zaibatsu into a much weaker body by SCAP. Although this claim is questionable, it is clear that the bureaucrats found themselves once again in a position to play a major role in rebuilding Japan. Second, one needs to give an observation as to how the institutional changes took place throughout the modern Japanese history. From the Meiji Restoration to the "Showa Democratization" in the late 1940s, or even up to today when Japan is under pressure from the West to force Japan to reform its economic system, all of the drastic changes that have taken place during the Modern Era have been made under pressure from the outside-”gaiatsu.” Throughout the history of Modern Japan, there has been nothing revolutionary caused by a public uprising. Starting from the Meiji Restoration, as stated earlier, Japan was literally forced to open itself by the Western powers. Although Japan was responsible for whatever decisions it made in the following events, it is undeniable that gaiatsu had 31 32 been one of the key elements in Japan's decision making. In the Showa Democratization, one sees a similar trend. The Constitution of 1947 was conferred from above just as was the Meiji constitution of 1889. For the first time and at least in an institutional sense, a truly democratic government was established. It was, however, not something acquired through public demand. It was forced upon Japanese society by SCAP. Although the public accepted it, this notion that the government was not their own creation naturally brought a lack of public attachment to the new government. An important implication one sees here is that, although these changes that have taken place in the postwar era were indeed drastic, in terms of the separation between power and authority, there was hardly any change. The only change taking place was the transference of authority from the monarch to the Diet. With regard to power, the bureaucracy was still in control. Even though there was enlarged public participation in politics due to the end of the restrictions over the franchise and the considerable degree of social mobilization achieved in the labor, industrial, and farming sectors, the lack of public attachment to the government hardly brought any significant grass root support to the career politicians which might have given them the controlling power in Japanese politics. Thus, along with the urgency of the economic recovery, public indifference to the government put the bureaucrats again in position to carry out the economic and political reconstruction of Japanese society almost single-handedly, as they did during the Meiji Era. Is the Japanese Bureaucracy Coercive? As one can see from the above discussion, it is more valid to say that the continuous control of power in the economical and political stages of Japanese society by the bureaucracy is not so much due to something they had control of but rather due to something they did not have much control over. This creates room in the public mind to tolerate the way the Japanese bureaucracy functions. Accordingly, in policy implementation, the bureaucrats are not as coercive and influential as Chalmers Johnson and the other Japan bashers claim them to be. In order to support his argument that the Japanese bureaucracy is coercive and unusually influential, Johnson raises two points. One is the overwhelming percentage of bureaucracy-drafted legislation in comparison with the scarcity of member bills introduced in the Diet. The other is the perpetuation and strengthening of the prewar pattern of bureaucratic dominance by the influence of former bureaucrats within the Diet. According to Johnson, 91 percent of all laws enacted by the Diet under the Meiji Constitution originated in the executive branch, not in the Diet.3 Similarly, in the first Diet under the new constitution, May 20 to December 9, 1947, the cabinet introduced 161 bills and saw 150 enacted, while members of the House of Representatives introduced only 20 bills and saw 15 enacted.4 Johnson depicts this Japanese bureaucratic dominance on legislation as if it were happening only in Japan. As John Owen Haley points out in his book, Authority without Power: Law and the 32 33 Japanese Paradox, contrary to Johnson's argument, bureaucratic dominance over legislation is not a peculiar occurrence seen only in Japan. It is quite a common practice among nations with parliamentary systems such as the United Kingdom, Germany, or France. For example, in the United Kingdom, the administrative department predominantly prepares and drafts legislation, and a very small proportion of the work of Parliament comes from private member bills.5 Similarly, both in Germany and France, the bureaucrats dominate legislation by originating about 75 percent of all legislations.6 With regard to the influence of former bureaucrats within the Diet, the bureaucrats indeed seemed to strengthen their influence by their participation in the Diet. Particularly, in 1949 when Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida, a former high-ranking bureaucrat of the ministry of Foreign Affairs, established in his third government the bureaucratic leadership structure (kanryo shudo taisei), bureaucratic dominance in politics seemed to be perpetuated.7 During the postwar period, as represented by Yoshida, most of the prime ministers in Japan started their careers as bureaucrats, indicating that such perpetuation could be real. However, contrary to Johnson's claim, the postwar constitutional order has actually reduced bureaucratic influence. Except in the 1949 and 1952 elections, in which a substantial number of former government officials entered the Diet, 37 and 48 respectively, the political gains by the ex-bureaucrats in any postwar election have been rather insignificant. They exceeded no more than a dozen in number of the seats in the Diet.8 Also, as well illustrated in the fact that, just in the last two decades, career politicians such as Kakuei Tanaka, Noboru Takeshita, or Toshiki Kaifu became Prime Ministers without any prior administrative experience, professional politicians have actually enhanced their political power with strong bases of local support. The two points Johnson raises in his attempt to portray the Japanese bureaucracy as a coercive and extraordinarily influential body, therefore, are refutable. In order to illuminate further the nature of the Japanese bureaucracy, one can make a comparative study between the Japanese bureaucracy and the American bureaucracy. From the general point of view, the Japanese bureaucracy is considered far more coercive and influential than that of the United States. In actuality, however, that is far from the truth. Although one needs to keep in mind that there is a difference between the two nations in terms of the practice of bureaucratic power: one is regulatory in the United States and the other developmental in Japan, the government intrusiveness into the economic and social life in the United states--from taxation through consumer and environmental regulation--is surprisingly far greater than in Japan. In fact, these regulatory controls were unknown to Japan until after World War II. Furthermore, it should be noted that most of the regulatory legislation in effect today was actually imposed upon Japan by SCAP during the occupation period. There has been no significant attempt by the bureaucracy to expand its power beyond the limits set by SCAP. Accordingly, the size of the Japanese bureaucracy is also not as big as that of the 33 34 United States. In 1910, for example, Japan had an estimated 185,045 national government civilian employees--one government employee per 265.8 persons, while in the United States in the same year there were an estimated 388,708 federal government employees-one federal employee per 237.7 persons.9 By 1970 the number of national government employees in Japan increased to 832,174, doubling the number of government employees per capita to one per 146.9 persons, while during the same period the number of federal government employees in the United States sharply went up to 2,981,574-one government employee to every 68.4 persons. Thus, it is neither its coerciveness nor its size which makes the role of Japanese bureaucracy distinguished from others. Instead, it is the effective process of the Japanese bureaucracy with the broad scope of "power," which comes without coercive legality. John Owen Haley calls it "consensus administrative managements.”10 Without coercive legal power to implement their policy unilaterally, the Japanese bureaucracy is by no means the unilateral actor in implementing a policy. Successful implementation of their policy quite depends on their ability to gain the consent from those who are affected by their policy.11 In this context, the distinction between public and private becomes obscure, and therefore, it gives more voice to those subjected by government policy in a negotiating process for formulating and implementing the policy. An important implication one should see here is that the power of Japanese bureaucracy does not come from the formerly institutionalized system, but outside of it, and it is based on the consent of the governed, not the coercive nature of bureaucratic authority as seen in the other industrialized democracies. Such consent between the Japanese bureaucracy and the public comes smoothly without any serious contention, which is usually seen when the process of governing takes place outside of the institutional main framework. It is not the case in Japan, as stated earlier, partially because such main framework itself is not its own creation, but something imposed on it by outsiders. Developmental versus Regulatory Chalmers Johnson points out in his book, MITI and the Japanese Miracle: The Growth of Industrial Policy, 1925-1975, that there are two different orientations toward private economic activities: the regulatory orientation and the developmental orientation, producing two different kinds of government-business relationships. He categorizes the United States as a nation with the regulatory orientation and Japan with the developmental orientation. What Johnson claims here is that, because of this difference in orientation, both nations are not playing a ball game against each other on a level playing field. The close relationship between the Japanese government and its private sectors through the developmental orientation tilts the playing field in favor of Japan. Unless something is done to force Japan to give up its unfair economic orientation, Japan's economic expansion is unstoppable and eventually will bring dire consequences to the world free economy. This argument, as refuted in the following discussion, has no grounds to be taken seriously. Japan indeed is taking a policy of the developmental orientation. It is nothing 34 35 disputable that Japan or any other nation for a certain reason, such as security, positions itself to achieve economic development. However, a contention arises when it comes to how Japan conducts economic practices to achieve such development. According to Japan bashers, among Japan's unfair practices the most notorious is the policy of targeting the growth of a certain industry to out-compete its counterparts in the international market. One of Japan’s bureaucratic agencies the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) has been under severe criticism for executing this policy.12 Johnson argues that MITI has control of making the decisions about which industries should exist or which industries should be eradicated, while in the United States, where the regulatory orientation predominates, such a decision is never made, but a closure of an industry, not eradication, takes place only as a result of free competition. Johnson's argument, however, once again is not free from flaws. No industrialized democracy exercises such power as to decide which industries should exist or not. In fact, throughout the modern era, there has been no case that any industry in Japan has been put out of business because of intervention from the government. No one can deny that a closure of an industry indeed happens. However, it is not because of the governmental decision to select a certain industry but primarily because of the change of the surrounding economic conditions for the industry. All MITI did or has been doing is to select a certain industry whose development is essential for the nation's need, particularly in terms of security. This is nothing new or unusual and is seen in many other nations. There are numerous such cases which can be cited here. For example, there are the joint ventures between governments and the main aerospace manufacturers in Europe. In Britain and France, the lucrative contracts with their governments for military aircraft and engines have been consistent help for the aerospace manufacturers to subsidize their commercial operations. Between 1945 and 1974, in Britain alone, the government contributed £741.2 million to the aerospace manufacturers in producing numerous commercial aircraft, receiving only £54.5 million in return for its investment.13 The most notorious case is the British government's effort to promote the nation's aerospace products overseas. In 1986, despite the earlier rejection by the Indian Ministry of civil Aviation, the Indian government decided to purchase a fleet of Westland helicopters after Prime Minister Thatcher made a personal intervention.14 What can be a better example of government intervention into private business than this?15 Similarly, although the United States in general takes a regulatory orientation toward private business activities, it is by no means completely free from the practice of government intervention into private sectors. One such example is the US government role in military industry. One may argue that, because of its military orientation, it has nothing to do with the civilian industry. One should not forget, however, that the military industry is one of the major parts of US economy, having many joint projects between the government and the private sectors. Those giant private corporations such as McDonnell Douglas and Lockheed have enormously benefited from their contracts with the government and government subsidies. In addition, military research creates highly valuable spin-offs which give such a competitive edge to the civilian industries such as 35 36 aerospace or computers. As these examples indicate, it is incorrect to stigmatize Japan as the only nation practicing this developmentally oriented policy of the government's intervention into private business, which is considered to be the anti-free competition. Also, with the changes in the international economic situation over the last two decades, it is becoming increasingly difficult to distinguish one nation with a regulatory orientation from other nations with developmental orientations. During these years, the US dominance of the world economic competition has come to an end, and the world has been multi-polarized in the economic power structure, creating stiff competition among the leading world economic powers. In addition, in today's high-tech age, technological advancement is so rapid that it takes less and less time for one particular technology to become obsolete and to be replaced by another. The gradual replacement of robotics in the production process by computerized machines in the United States today is a typical example of such rapidity in technological advancement. Under these circumstantial changes, contrary to their advocacy of free economy, most of the industrialized nations are today showing their inclination to move toward a developmental orientation for their private economic activities. Particularly such an inclination is prominent in the United States. Shifting its national priority from politics to the economy in the post Cold War Era and obliged to confront rising competition from the other industrialized nations, the United States has no other choice but adopt policies of joint effort between the government and the private section for targeting development of a certain industry. Bureaucracy as a Coordinator Thus, neither in the past nor in the present has there been justifiable ground to stigmatize Japanese bureaucracy as a core of Japan's unfair economic policies and its implementation of those policies. Yet, Japanese bureaucracy has been singled out exactly as such core of the problem and under constant criticism from Japan's trade partners. The part of such criticism seems to lie in the Western counterparts' distorted understanding of the role of Japanese bureaucracy (MITI) as a "coordinator." It is indeed important for a coordinator to be able to select prospective industries for over all economic expansion. However, it is equally important for it to be able to deal effectively with the industries in decay. In this aspect, MITI displays a contrasting policy to those of its counterparts. MITI well understands that effective and continuous economic development can be achieved by moving from one industry to another for higher-valued products, starting from labor-intensive and low technology products such as textiles to less labor intensive and medium technology such as steel or shipbuilding, and finally to sophisticated and high technology products such as computer. In each transition, in addition to promoting a high prospective industry, MITI has coordinated the withering industries by encouraging them to move on to more prospective industrial fields. one successful case of MITI's coordination is the steel industry. While Japan's steel output was declining in 1980s as a result of the industrial shift, South Korea doubled its steel production. This did not alarm Japan. On 36 37 the contrary, MITI understood such production growth would help South Korea to develop economically and increase its buying power for more advanced products made in Japan. So, both nations benefited from the industrial shift taking place in Japan. On the other hand, the United States takes a quite different approach to an industrial shift. While it has been making an effort to promote high-technological industries such as aerospace, computers, or semiconductors, it has been unable to take the similar step as MITI does to make a necessary change in the process of an industrial shift in dealing with a withering industry because of its political complexity such as the powerful lobbying and individual oriented cultural norm of US society. So, instead, the United States has continued to support the traditional industries in order to keep them alive. This difference in economic coordination between MITI and its counterparts is indeed one of the key factors which has made it possible for Japan to develop economically in such a miraculous way and out-compete the other developed nations in some industries, while its counterpart has not been able to cope with rather aggressive Japanese expansion and has begun to take it as serious threat to its economic status. Here, however, one should note that MITI's well-executed coordination is not the only factor for Japan's economic success. There are many other things that have contributed to economic success such as highly skilled work force, high-standard of education system, homogeneous society, or pro-business inclination. The United States and the other Western industrial powers, however, deliberately ignore all other factors but focus on MITI to distort its policies as being unfair and the primary causes for all the economic disputes existing between Japan and its counterparts, particularly in regard to the trade friction. Conclusion The Japanese bureaucracy survived two revolutionary events in the modern history of Japan: Meiji Restoration and Showa Democratization. Unless the fundamentals of the Japanese society change, there is no reason to believe that the Japanese bureaucracy will fail to do the same in the post Cold War Era. There are the voices advocating inevitable changes in the Japanese way of politics and economy in order to deal with the new economic and political environment. They are, however, far from becoming significant enough to be taken seriously. It is likely, therefore, that an unchanging trend of the bureaucratic control of Japanese economy and politics will continue. So will the scrutiny of the Japanese bureaucracy by the Japan bashers. A question her is how to end the seemingly never ending “blaming game?” If there is any answer to the question, as one can infer from the above discussion. it has to be in the hand of the Japan bashers. 1 Chalmers Johnson gives one interesting example as one of the most serious consequences of adopting this system. He points out that Japan’s decision to have war against the United States and its allies was one of such outcomes; it was a decision in which neither the monarch nor the parliament took part in.. See Chalmers Johnson, MITI and the Japanese Miracle: The Growth of Industrial Policy, 1925-1975, (Stanford: Stanford 37 38 University Press, 1982), p. 36. 2 Eiichi Isomura, ed., Gyosei Saishin Mondai Jiten (Dictionary of Current Administrative Problems), (Tokyo, 1972), p. 705. 3 Chalmers Johnson, MITI and the Japanese Miracle: The Growth of Industrial Policy, 1925-1975, (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1982), p. 47. 4 Charmers Johnson, MIT and the Japanese Miracle, p. 47. 5 John Owen Haley, Authority without Power: Law and the Japanese Paradox, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991), p. 140. 6 John Owen Haley, Authority without Power, p. 140. 7 Chalmers Johnson, MITI and the Japanese Miracle: The Growth of Industrial Policy, 1925-1975, (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1982), p. 45. 8 John Owen Haley, Authority without Power: Law and the Japanese Paradox, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991), P. 141. 9 John Owen Haley, Authority without Power, p. 143. 10 John Owen Haley, Authority without Power, p. 144. 11 In his book, A History of Japan’s Government-Business Relationship: The Passenger Car Industry, Phyllis A. Genther elaborates the cooperative nature of Japan’s Government-Business relationship in his case study on Japanese auto-industry. 13 Phillip Oppenheim, Japan without Blinders: Coming to Terms with Japan’s Economic Success, (Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1992), p. 129. 14 Phillip Oppenheim, Japan without Blinders, pp. 129-30. 15 Akio Morita--One of the founders of SONY Corporation--made the following comment about Mrs. Thatcher’s personal intervention: “Japan Inc., as many Americans and Europeans call our governmentbusiness relationship, is second-rate compared to the French government-business relationship or English one for that matter. For one thing, I have never heard a Japanese head of state or head of government try to sell in that way.” See Phillip Oppenheim, Japan without Blinders: Coming to Terms with Japan’s Economic Success, (Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1992), p. 130. 38