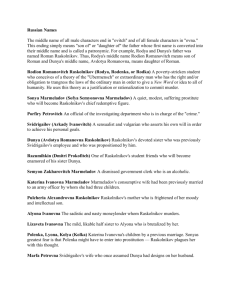

419sample synecdoche

advertisement

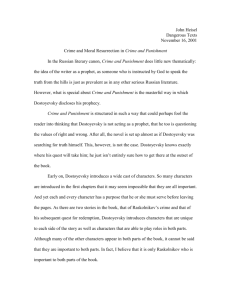

Yet all told he simply had no faith in himself, and he was looking everywhere, like a slave, for valid objections, groping his way, as though someone were forcing and pushing him. This last day, however, which had so unexpectedly decided everything at once had caught him up almost automatically, as if by the hand, and pulled him along with unnatural power, blindly, irresistibly, and with no objections on his part, and he was caught as if by the hem of his coat in the cog of a wheel, and being drawn in. (68) Dostoyevsky delves into Raskolnikov’s deluded state of mind within this passage. Raskolnikov vascillates in his views on religion, which is made evident in the author’s use of the word “faith.” Raskolnikov’s discord with a system of beliefs has extended so far that he cannot even believe in himself. Yet despite this apparent lack of faith, Raskolnikov almost unknowingly searches for some type of higher reasoning. Dostoyevsky implicates this desire through his emphasis in sight or the lack thereof throughout the paragraph; Raskolnikov is “looking everywhere” but is currently “groping his way” and following “blindly.” He has fallen astray from the correct path—he is currently in a state of confusion, lost within darkness. Yet, for all this questioning and uncertainty, Dostoyevsky makes clear that this is a self-selected exile from truth that Raskolnikov simply refuses to acknowledge. Raskolnikov cannot bear the responsibility of his deviation. The passage is riddled with excuses—“someone were forcing and pushing him”, he was “like a slave” and was “caught, as if by the hem of his coat in the cog of a wheel, and being drawn in.” Raskolnikov cannot accept his actions, insistent that he has neither free will nor choice in the matter, which is ironically at odds with his apparent absence of faith or belief in higher powers. Yet he even subverts his vehement denials. He is aware that this darkness is an “unnatural power.” By calling it “unnatural”, Dostoyevsky demonstrates that Raskolnikov realizes he has strayed from his true path, his norm. In fact, to listen to the darker impulse is “unexpected”—it comes as a surprise to himself that he would deviate from religion and truth. Raskolnikov listens to these dark urges as he finds them “irresistible” and he has “no objections on his part.” Thus, he betrays his own innocence by conceding that he chooses not to object what he knows on some level is wrong. Even by claiming a cog catches him, he subtly acknowledges that this idea is wrong, for to be caught in a cog would lead to his crushing demise. The dissonance between realization and denial coupled with faith and nothingness mirrors the conflict BE MORE SPECIFICplaying out throughout Russia in Dostoyevky’s entire novel. Crime and Punishment uses Raskolnikov as a proxy for the author’s own ideological struggle. Dostoyevsky’s characters attempt to reconcile Nihilism with old Christian values. Raskolnikov scorns morality as a trapping of society, which he views himself as being superior to in comparison. He murders the pawnbroker because he wishes to test himself—to prove to himself that he can deny his conscience and truly exist solely for himself; “I didn’t kill a person, I killed a principle…I want to live myself, or better not live at all” (264). However, his failure to cope with his actions and determination to reject the guilt he feels culminates into agonizing delirium as he essentially punishes himself in a self-flagellation that society could not even inflict upon him. For all his espousals of nihilistic glee and mockery of religion, he cannot bring himself to forgo caring. He finds himself disgusted by Marmeladov, Svidrigailov, and Luzhin, all of whom represent true hedonism. He leaves money for Marmeladov’s distraught wife (24), is intrinsically repulsed by Svidrigailov’s sexual perversion—evident in his naming the attempted rapist “Svidrigailov” (45), and his refusal to allow Dunia to wed Luzhin (43). Thus, Dostoyevsky condemns complete nihilism with his proxy character’s inability to accept it. Try as he might, Raskolnikov cannot eschew all morals in the face of such overt sinfulness. As for his own repeated attempts at approaching complete nihilism, Raskolnikov continually deludes himself. He mocks Sonia as a “holy fool” for remaining devout when God does not save her from prostitution, yet he insists she reads him the resurrection of Lazarus, which he told Porfiry he believed literally occurred. His belief in Lazarus implies that he believes in miracles, events preordained by a higher power. KEEP GOING Dostoyevsky illustrates a journey of spirituality through Raskolnikov. The novel may superficially appear to chronicle the murder and its eventual discovery, but the true intent of the novel explores the clash of the modern and new as the author questions the validity of a new ideology. Ultimately, Crime and Punishment denounces nihilism, for like the story of Lazarus, Raskolnikov suffered from skepticism like the Jews and it was not until they experienced a miracle, or rebirth that “ many of the Jews which came to Mary, and had seen the things which Jesus did, believed on him” (313). Raskolnikov’s murder was an attempt to decry divinity, yet ultimately it is his rediscovery of it with Sonia that truly releases him from the prison of his own mind. He completes his journey and experiences a resurrection and new belonging within society.