KATHY-ANN TAN

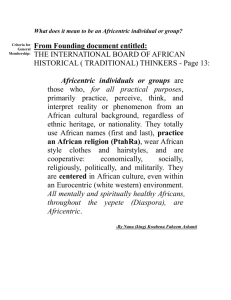

advertisement