Lowell Girls

advertisement

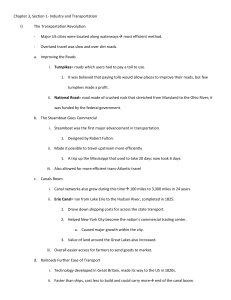

Story of a Lowell Girl from Vermont With 14 words, Mary Paul made her bid to join a revolution. "I want you to consent [agree] to let me go to Lowell if you can," she wrote to her father on Sept. 13, 1845. She wanted to move south to .the Massachusetts mill town where she hoped to get a job. In doing so, she would join the first generation of American women to be regular wage earners. Mary Paul laid out her reasons. "I think it would be much better for me than to stay about here," she wrote. "I could earn more to begin with than I can anywhere about here. I am in need of clothes which I cannot get if I stay about here and for that reason I want to go to Lowell or some other place." She was living with an aunt and uncle in Woodstock while her widowed father continued to live on the family farm in Barnard. She had recently left a job as a domestic servant for a family in Bridgewater, and knew that the local job market was not good for women. In Lowell, her prospects would be brighter. When she left Vermont several weeks later, having received her father's blessing, she was still only 15. The Lowell she entered was full of others just like her. The year she arrived, the city's textile mills employed roughly 1,200 Vermont farm girls. Thousands of other girls and young women from Vermont found jobs at mills around New England. (Others never even left the state, finding work in the state's mill towns, like Middlebury, Winooski, Windsor and Bennington.) But Lowell was the most common destination. The mills hired people specifically to recruit young women, but the mills' somewhat high wages (higher than they could receive on the farms) made their jobs easy. Mostly the recruiters just arranged transportation for girls as they headed south for work. The Lowell mills, indeed all of America's textile mills, owed their existence to a brilliant bit of memorization, which amounted to what we today would call industrial espionage. When Boston businessman Francis Cabot Lowell visited English mills in 1810, the technology used there was a closely guarded secret. England had recently made major technological leaps in the milling process and wanted to preserve its advantage. Lowell wanted equally to overcome it. But he couldn't simply buy some of this new machinery. Exports were banned. So he took what appeared to be a casual tour of an English mill and managed to memorize the factory's precise workings. When he returned to the United States, he built machines that matched his memories and eventually built textile mills in the town of East Chelmsford, which after his untimely death, was renamed Lowell in his honor. New Englanders had heard the horrors of the child labor employed in Britain and by some American factory owners, and they wanted no part of it. They would create mills that treated and paid their workers decently. Farm girls like Mary Paul were the solution. They quickly became skilled but also rather inexpensive laborers. New to the workforce, they seemed glad for the money they received, even if it was half what their male co-workers were paid. The country’s leaders praised the mill system. Since mill girls were expected to keep their jobs for only a few years - long enough to earn some money, find a husband, and move on, they would prevent the formation of a permanent laboring class, which society viewed as an evil. If mill owners were going to rely on a young workforce - though not young enough to be considered child labor - and one that was largely female, they were going to have to control most aspects of workers' lives to ensure appropriate behavior. How else could they convince fathers to allow their daughters to work far from home? Unmarried female workers were required to live in one of the company-sponsored boardinghouses near the mills. A "housemother" ran each boardinghouse and enforced the rules, which included a strict curfew, limits on visitors, mandatory church attendance and the judicious use of candles. "I have a very good boarding place," Mary Paul wrote her father, "have enough to eat and that which is good enough. The girls are all kind and obliging. The girls that room with are all from Vermont and good girls too." For their rent, which was deducted from their paychecks, the young women received three hearty meals a day, two of which included meat. They would need their strength. When Mary Paul reached Lowell, mill girls worked six days a week - 13 hours a day on weekdays and eight hours on Saturdays for a total of 73 hours. D:\533573855.doc Growing up on farms had trained the young women for long days. What took some getting used to was the regimen of factory life. "At half past 4 in the morning the bell rings for us to get up," Paul explained in a letter, "and at five for us to go into the mill. At seven we are called out to breakfast (and) are allowed half an hour between bells and the same at lunch. . ." Familiar with the relative calm and quiet of the farmyard, the girls entered the mill to find, in the words of one, that "the sight of so many bands, and wheels, and springs in constant motion, was very frightful." Then there was the clatter. One complained that she would leave each day with "the noise of the mill in my ears, as of crickets, frogs and jew’s-harps, all mingled together in strange discord." Mary Paul at least had some downtime on her first job. Like many young workers, she was hired as a "doffer" responsible for removing full bobbins from spinning frames and replacing them with empty ones. The job required quick hands and constant motion, but only for 15 minutes each hour. The factories exposed workers to unhealthy conditions. The air was filled with lint from the yarn and fumes from the whale-oil lamps that were attached to each loom. To keep the yarn from drying and snapping, mist was pumped into the rooms. Windows were nailed shut to keep humidity levels high. The factories' air weakened lungs during an era when tuberculosis and other pulmonary ailments were common. Mill owners found that they didn't have to pay for the care of sick workers, because women generally remained close to their families and returned home if they became ill. Some people claimed that many mill workers "went home to die." Death could also come suddenly. "My life and health are spared while others are cut off," Mary Paul wrote her father less than a month after she arrived. "Last Thursday one girl fell down and broke her neck, which caused instant death. She was going in or coming out of the mill and slipped down, it being very icy." The same day, she reported that a male worker was killed by a train on the tracks beside the factory. For all the dangers, Mary Paul and other young women found reasons to prefer the life they found in Lowell to the ones they had left behind. In Lowell, in addition to earning their own money, they could use their precious spare time to frequent local libraries that had been established for them to attend scholarly lectures at the lyceums that had sprung up around the city. Paul even encouraged her brothers to come to Lowell, where she was sure they would find good jobs. They never heeded her advice, however, perhaps because Lowell represented a step up for Vermont farm girls, but not for farm boys, who could earn a reasonable wage at home. Her love of Lowell, however, didn't last. She moved briefly to Claremont, N.H., where her father had relocated. Perhaps in love with of the better pay she might expect in Lowell, she returned to that city in November 1848. She found Lowell crowded with people seeking mill work. Mill after mill rejected her. She turned in desperation to her former boss. Mary Paul had last worked in the mill's dress room, and there she returned. In the dress room, yarn was prepared for weaving. The job was much better paying than many in the factory. It was also one of the hardest. She found the workload almost unbearable. "It is very hard indeed and sometimes I think I shall not able about to endure it," she wrote her father. "I never worked so hard in my life but perhaps I shall get used to it." Worse, management had just announced wage cuts. "The companies pretend they are losing immense sums every day and therefore they are obliged to lessen wages," she wrote, "but this seems perfectly absurd to me for they are constantly making repairs and it seems to me that this would not be if there were really any danger of their being obliged to stop the mills." Mary Paul and New England farm girls like her were finding that mill owners no longer needed them. Their pay was being cut and their jobs being taken because a flood of immigrants was arriving in the United States. The new arrivals were willing to work for lower wages. 1. Why did so many parents of young farm girls (whom they probably loved very much) allow/encourage them to go to work these long hours in the mills? 2. Who was Francis Cabot Lowell, and what role did he play in America’s Industrial Revolution? 3. What was it like initially to be a “Lowell Girl” and why did it change? D:\533573855.doc