The State and Development of E-Commerce in Serbia

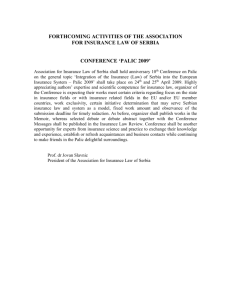

advertisement