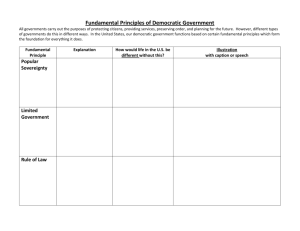

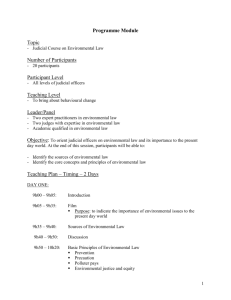

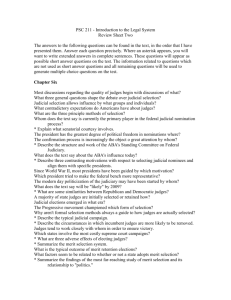

Democracy and Judicial Review

advertisement