Outlaw: Hero or Anti-Hero? English Myth-Making

advertisement

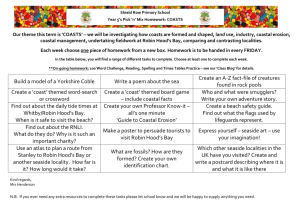

Discussion Paper for Videoconference with Pace University, 16th April 2008; Dr C. Griffin The Outlaw: Hero or Anti-Hero? English Myth-Making Robin Hood and the Monk (c. 1450) Text: http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/teams/monkint.htm http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/eng/child/ch119.htm http://www.internationalhero.co.uk/h/hood.htm http://www.boldoutlaw.com/robages/robages2.html OUTLAW does not appear in court for his crimes, places himself instead beyond the grasp of the forces of law and authority, such as the sheriff. Therefore he is deprived of social identity, and status and, to an extent, power. The outlaw abandons society and society disavows him. Yet social values, issues and events are of great concern to the figure of Robin Hood. He is no longer a MEMBER of society, but in several adventures Robin is drawn into society where he wants to impact on events or participate in some way. For example, he stops a marriage, intervenes in disputes, rescues individuals, or, in Robin Hood and the Monk, he attends church services. Robin in particular commutes between the world of culture and the world of outlawry; he exists between the normal social order and the associal void that the concept of outlawry suggests SOCIAL STATUS OF OUTLAW The medieval Robin Hood is frequently imagined as a projection of some late medieval class (important in estates satire, cf the ‘General Prologue’ to Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales) He displays some affinity with the peasantry, but the ballads of the late Middle Ages seem to be addressed to a gentrified audience – this implicitly confirms the anomalous nature of this figure, and outlaw with a link to one or more sectors of established society Frequently referred to as a yeoman – thus he is a defender of, and paradoxically even a member, of the yeomantry – which was a class of free peasantry emerging in the late Middle Ages He’s NOT a disinherited knight until much later in the tradition: in several of the medieval ballads, though, he is a defender of the knightly class who have fought the Crusades. He supports a social superior, and in doing so he reveals an awareness of a hierarchical distinction between a knight and a yeoman by asking for payment in one ballad (A Gest of Robin Hood) There is also the overwhelming sense from the literature that Robin can both grant and tale away status – he is “master” (not king, notably) of his greenwood – and has ultimate power in his dominion. SO in this sense does he uphold social order or create a new version? FOREST / GREENWOOD HUNTING: Means of survival in the forest / passtime or sport / assertion of power in the natural world; the outlaws are professional hunters living in the woods with no taste for ‘civilised’ life of the court or town Discussion Paper for Videoconference with Pace University, 16th April 2008; Dr C. Griffin Greenwood is a locus amoenus; it functions as a place of nature that is juxtaposed with the town (a place of culture) where the sheriff has domination the forest, however, is the king’s sphere of influence – it is therefore an anomaly existing between culture and nature. BUT nature is owned, protected and theoretically controlled by the most powerful and representative member of society. Therefore the world of Robin Hood is a distinctly liminal one in which he effectively usurps of takes over the role of the king: symbolic association with the king’s deer and the killing of that royal animal Outlaws dress in GREEN – the colour of their natural environment. They live amongst the deer on which they depend, to the point that there is almost an identificaiton of between the hunter and the hunted. ORIGINS In that sense, the literary and cultural history of the outlaw and, specifically, Robin Hood, has been associated with something that is liminal, and in itself outlawed or banned To begin with, he is associated in a very deep way with folk ritual and folk tale (hence the forest and the association with deer) But Robin also has close associations with the Christian churches, and in particular the cult of Mary. So the Robin we receive today is a weird blend between pagan and Christian The Cult of Mary was brought into England by early pilgrims returning from the Holy Land and Santiago de Compostela. She became associated in England with May and May Day, and was paired off, by the Saxons, with Robin Hood or Robin Goodfellow, the name means, in early French, either ram or devil. So originally he is a sort of a devil-god, with horns and ram’s legs – very sexual and black – sometimes surrounded by a coven of witches. Here the story becomes complex because Robin Hood became associated with May Day celebrations. According to Walker, an early 20th century historian, the origin of the ballads we are looking at is further complicated by an actual Robin Hood: born in Wakefield, Yorkshire, sometime between 1285 and 1295, and in the service of Edward II between 1323-1324. He married Matilda – who became the Marian figure – and, also, the thirteenth member of the outlaw fraternity to which Robert Hood belonged. These figures became associated with defiance of the church and upheld the May Day orgies and celebrations in the English countryside, where Robin would preside as Lord of Misrule and Matilda would have worn her proper clothes ass his bride. May Day was even merrier than Yuletide; Maypoles, cakes and ale, wreaths of flowers, lover’s gifts, archery contests, and wrestlings. It was also a time when marriages took place under the greenwood trees, endorsed first by a Friar Tuck figure and then officially in the Church porch. Whole villages took part in these anti-establishment fertility rituals, commonly known as “mayings” or “Robin Hood games”, which were outlawed by Puritans much later on. BUT you also have a literary tradition emerging from this, with the focus on the rebellious exploits of the infamous outlaw. There is, however, an outlaw tale that was committed to paper much earlier than any of the Robin Hood ballads: Discussion Paper for Videoconference with Pace University, 16th April 2008; Dr C. Griffin An Outlaw of Trailbaston (Anglo-Norman, c. 1305) -The only reason that the medieval outlaws exist for us today is that they were written down – might seem obvious, but it provides a reminder of the fragility of our knowledge of the Middle Ages, of pre-print culture, and of outlaws from that time. That knowledge is dependent on the INCIDENTAL survival of a scattered body of references and texts that are now preserved in literary manuscripts from the 13 – 16th centuries. IMPORTANTCE OF TEXT AND THE WRITTEN WORD 13th century onwards: the business of government began to be carried out increasingly using documents, letters, epistles, rolls, charters etc – became a ‘document driven culture’ Hence all the great rebellions – carried out by those who couldn’t access the written word, like the Peasant’s Revolt of 1381 – attacked the repositories of the written word – it symbolised power and control There are lots of references to the written word in outlaw texts: the public authority – wither the king or his institutions – usually communicate with the outlaws not through direct intervention but the written word: In Robin Hood and the Monk we see a letter that comprises written instructions ordering the individual to come before the king and his courts – the letter from the Monk complaining of the losses he has suffered at the hands of Robin and his men is stolen by Little John and taken by him to the King. The King then authorises an instrument ordering the sheriff to bring Robin to him (ll. 231-4) When the sheriff receives the letter, robin’s escape from prison causes him considerable anxiety because he is now unable to respond effectively to the letter: (ll,295-8) Between these two passages we are told that the letter to the sheriff is authenticated by the king’s privy seal – (253) – much more weighty and powerful than the great seal – and has implications of penalties or forfeiture for anyone unable or unwilling to carry out its orders. We also have a form of petition by the outlaw in Trailbaston, which is a high-status text in comparasion. The ONE type of written petition that is ABSENT from outlaw literature is the type that pardons the outlaw, allowing him return to the king’s peace. The outlaw in Trailbaston complains that he “dare not come into peace among my kinsmen”. For the medieval outlaw, texts AND writing represented a fundamental threat. His flight to the Greenwood represented an escape from the authority of his own record as preserved in the plea rolls of the court. Suggestions for Discussion: -the endurance of a myth and the richness and scope of the literature associated with that myth Discussion Paper for Videoconference with Pace University, 16th April 2008; Dr C. Griffin -the process of myth-making, and the notion that the legend is frequently re-worked and re-visited, yet it retains certain core concepts and features that make it instantly recognisable, and that an audience – be it late-medieval or early 21st century – will come to expect. Particularly germane since the BBC has recently reinvented the Robin Hood legend in the first major TV series since the influential Robin of Sherwood of the early 1980’s. -The idea that the outlaw falls short of being ‘heroic’ – are outlaw texts emerging from the heroic tradition? -Differences between Arthur and Robin; have they been treated differently by literary scholarship? Later Developments: Outlawing the Outlaw Early Modern Period: Robin Hood went from being immensely popular amongst all ranks or estates of society to being quite literally outlawed. He represented a threat both national stability and puritan economy in the sense that he was associated at once with fertility and sexuality and populist disenchantment. Because of his popular appeal, Elizabethan dramatists made the outlaw a marginal figure (Shakespeare famously eschewed Robin – too controversial, but pointed on more than one occasion to the idyllic greenwood and the possibilities for transgressive behaviour that locus provided). Elizabethan authorities were, according to David Wiles, “determined to prevent any institutional expression of egalitarian sentiment”. Romantic and Victorian: Firmly part of the literary landscape of England and of the postNapoleonic war, industrialised English society, struggle for universal suffrage. There was an interest in archaism and the past, what Marilyn Butler calls “popular antiquarianism”, and which led to various publications: 1765: Thomas Percy’s Reliques of Ancient Poetry 1777: Thomas Evans, Old Ballads 1795: Thomas Ritson, A Collection of All the Ancient Poems, Songs and Ballads Now Extant Relative to the Celebrated English Outlaw 1806: Wordsworth, “Rob Roy’s Grave” 1810: Scott, “The Lady of the Lake” 1814: Byron, The Corsair 1819-20: Keats and Reynolds The Novel Scott, Robin Hood (1819), and Ivanhoe (1820). Relocated Robin in a historical and national frame of reference, but also, influenced by Keats and Reynolds, gave Robin the context of natural values and a quintessential Saxon register of Norman oppression. Racial issues, matters of nationhood and identity, & violence characterise the novel. Some Reading: Child, F. J. (ed.). The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, vol. III. New York: Dover, 1962. Contains all Robin Hood and other outlaw verse Dobson, R. B., & J. Taylor. Rymes of Robyn Hood: An Introduction to the English Outlaw. London: Heinemann, 1976. All of the RH verse texts, along with an excellent introduction. Knight, S. Robin Hood: A Complete Study the English Outlaw. Oxford: Blackwell: 1994. Discussion Paper for Videoconference with Pace University, 16th April 2008; Dr C. Griffin Phillips, H. Robin Hood: Medieval and Post-Medieval. Dublin: Four Courts, 2005. Websites: see Blackboard