greek art - ArtHistorySurvey1

advertisement

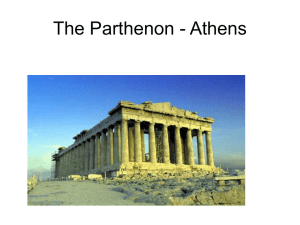

24 CHAPTER FIVE GREEK ART The Geometric Style Key Images Late Geometric belly-handled amphora by the Dipylon Master, p.104, 5.2 Man and Centaur, perhaps from Olympia, p.105, 5.4 Geometric tripod cauldron from Olympia, p.106, 5.6 Griffin-head protome from a bronze tripod-cauldron, from Kameiros, Rhodes, p.107, 5.7 The Geometric style dates from 1000-700 BCE. Early Geometric vase-painting was highly abstract, with geometric designs. In Late Geometric vase-painting abstract human figures interact in narrative scenes. During this period there were several flourishing centers of pottery production, including those in Athens and Corinth. The various shapes of Greek vases were developed according to both purpose and aesthetic forms. The Dipylon amphora takes its name from the place where it was found—the cemetery just outside the Dipylon Gate in Athens. This amphora functioned as a funerary monument for a wealthy woman. Holes in the base of the amphora allowed liquid libations to be poured into the vase and then into the earth below. The belly-handled amphora was typically used to house the female’s remains in a funerary context, while the neck-amphora was used for storing wine or for the male’s remains. In the Geometric style of vase-painting, human and animal forms are reduced to simple geometric shapes. The Orientalizing Style Key Images The Ajax Painter, Aryballos, p.106, 5.5 From ca. 725–650 BCE a new style of painting emerged, replacing the Geometric style in many areas. One of the foremost centers of production for this style was Corinth. In Corinth this style is exemplified by registers of real and imaginary animals. The source of the decorative motifs on the pottery from this period can be traced to the arts of the Near East, Asia Minor, and Egypt. 25 Spirals, rosettes and interlacing bands combine with the earlier geometric designs on many of the vases. Greek myths and legends often furnished the narrative subjects for these vasepaintings. Archaic Art Archaic Architecture Key Images The Temple of Hera I and the Temple of Hera II, Paestum, p.110, 5.10 Interior, Temple of Hera II, p.111, 5.11 Archaic Sculpture Key Images Kore (Maiden), p.113, 5.14 Kouros (Youth), p.113, 5.15 Kroisos (Kouros from Anavysos), p.114, 5.16 Kore in Dorian Peplos (Peplos Kore), p.115, 5.17 Kore, from Chios (?), p.115, 5.18 Central portion of the west pediment of the Temple of Artemis at Corfu, p.116, 5.19 Battle of the Gods and Giants, Temple of the Siphnians, Delphi, p.117, 5.22 Dying Warrior, from the west pediment of the Temple of Aphaia, Aegina, p.118, 5.24 Dying Warrior, from the east pediment of the Temple of Aphaia, Aegina, p.119, 5.25 Archaic Vase-painting Key Images Achilles and Ajax Playing Dice, black-figure amphora signed by Exekias, p.120, 5.26 Euthymides, Dancing Revelers, red-figure amphora, p.121, 5.27 Douris Painter, Eos and Memnon, interior of an Attic red-figure kylix, p.121, 5.28 The Archaic period dates from the mid-seventh century to ca. 480 BCE. Black and red figure style vases predominated during this period. The Doric and Ionic orders emerged during this period. The Doric order is the oldest and the simplest. The Ionic order is named after Ionia, a region on the West Coast of Anatolia and the island off the Coast. Archaic kouroi and korai were highly stylized. The Archaic kouroi are idealized with their arms rigidly to their sides and their left foot taking a step forward. Kouroi are always nude and have been found in a variety of contexts functioning as funerary markers and votive offerings. Both kouroi and korai are often depicted with an Archaic smile that is not reflected in the eyes. 26 Archaic korai are also idealized, but they always appear clothed. Their feet are placed together. They often held a small object (a bird or a pomegranate) in their left hand. In Greek sculpture there is a general trend towards increased naturalism from the Archaic to the Hellenistic periods. This trend can be seen during the Archaic period as well when comparing the New York Kouros (Fig. 5.15) with the later Anavysos Kouros (Fig. 5.16). Black-figure vase painting dates from the late 7th century BCE. Toward the end of the 6th century BCE red-figure vase painting was developed, gradually replacing blackfigure between 520 and 500 BCE. The Classical Age Early Classical Sculpture (“Severe Style”) Key Images Kritios Boy, Athens, p.122, 5.29 Charioteer from Motya, Sicily, p.122, 5.30 Zeus or Poseidon, p.123, 5.31 Diskobolos (Discus Thrower), Myron, p.125, 5.32 Doryphoros (Spear Bearer), Polykleitos, p.125, 5.33 Riace Warrior A, p.126, 5.34 Photographic reconstruction of the Battle of the Lapiths and Centaurs, Temple of Zeus at Olympia, p.127, 5.35 Atlas Bringing Herakles the Apples of the Hesperides, p.128, 5.36 Architecture and Sculpture on the Athenian Akropolis High Classical Akropolis (view from the west), Athens, The Propylaea, p.129, 5.37 Iktinos and Kallikrates, The Parthenon, Akropolis, Athens, p.130, 5.39 Model of Athena Parthenos, by Pheidias, p.131, 5.40 Dionysos from the east pediment of the Parthenon, p.133, 5.42 Three Goddesses, from the east pediment of the Parthenon, p.133, 5.43 Lapith and Centaur, metope from the south side of the Parthenon, p.134, 5.44 Lapith and Centaur, metope from the south side of the Parthenon, p.134, 5.45 Frieze above the western entrance of the cella of the Parthenon, p.135, 5.46 Horsemen, from the west frieze of the Parthenon, p.135, 5.47 East frieze of the Parthenon, p.135, 5.48 Nike, from the balustrade of the Temple of Athena Nike, p.137, 5.49 Grave Stele of Hegeso, p.137, 5.50 Mnesikles, The Propylaea, Akropolis, Athens, p.138, 5.51 Temple of Athena Nike, Akropolis, Athens, p.139, 5.52 The Erechtheion, Akropolis, Athens, p.139, 5.53 27 Late Classical Architecture Theater, Epidauros, p.140, 5.54 Late Classical Sculpture Polykleitos the Younger, Corinthian capital from the tholos at Epidauros, p.142, 5.58 Head of Herakles or Telephos, Temple of Athena Alea, Tegea, p.143, 5.59 Aphrodite of Knidos, Praxiteles, p.143, 5.60 Hermes, Praxiteles, p.144, 5.61 Apoxyomenos (Scraper), Lysippos, p.144, 5.62 Late Classical Painting Niobid Painter, Red-figure calyx krater from Orvieto, p. 145, 5.63 Reed Painter, White-ground lekythos, p.145, 5.64 The Early Classical period dates from ca. 480–450 BCE. This period in sculpture is known as the ″Severe Style″ since works from this period exhibit greater naturalism and do not have the Archaic smile seen in the earlier period. This increased naturalism can be seen in the contrapposto of the Kritios Boy and Doryphoros. Heavy ″doughy″ drapery is also characteristic of the Early Classical period, and can be seen in the pediment sculptures from the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. The Greek idea that nature can be ordered and idealized by human intellect was demonstrated by artists and architects of the Classical period. During the Early Classical period Polykleitos, who sculpted the Doryphoros, wrote a book entitled The Canon (now lost) in which he established standards for the representations of the human body. Many Greek sculptures, with the exception of Archaic kouroi and korai and later bronze statuary, are Roman copies after lost bronze Greek originals. The High Classical period dates from ca. 450–400 BCE. The monumental building program for the Akropolis in Athens was funded by Perikles. The Parthenon, dedicated to Athena Parthenos, was the center of cult worship of Athena on the Athenian Akropolis. Contemporary building records indicate that Iktinos and Kallikrates oversaw the construction of the Parthenon and Pheidias oversaw the sculptural program. Iktinos and Kallikrates employed a ratio of proportions in building the Parthenon, a formula which dictates that the flanks of the building be twice as long plus one as the facades. This ratio was first used by Libon of Elis at the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. In addition to the ratio of proportions, the architects also used architectural refinements including entasis, inclination, and curvature. Because of the perfection of proportions and architectural refinements, the Parthenon became the gold standard for temple building from the High Classical period onwards. 28 The Late Classical period dates from ca. 400–325 BCE. During this period there was a shift in emphasis in temple construction with a formalization of form. This can be seen in the Theater at Epidauros and the Mausoleum at Halikarnassos. In the late 5th century we also see the development of the Corinthian capital, invented, Vitruvius tells us, by the metalworker Kallimachos. Corinthian columns were used in temple interiors originally, and do not appear on temple exteriors until the 2nd century BCE. Sculpture of the Late Classical period shows increased naturalism. One of the most well-known works from this period is Praxiteles′ Aphrodite of Knidos, commissioned by the people of Kos and ultimately purchased by the city of Knidos. Another hallmark of this period is a new interest in illusionism, which can be seen in Lysippos’ Late Classical Apoxyomenos. Hellenistic Architecture Key Images Paionios of Ephesos and Daphnis of Miletos, Temple of Apollo, Didyma, p. 147, 5.66 Hellenistic Sculpture Key Images Lysippos, Portrait of Alexander the Great, the ″Azara herm,″ p. 150, 5.70 Portrait Head, from Delos, p. 150, 5.71 Epigonos of Pergamon (?), Dying trumpeter, Pergamon, p. 151, 5.72 The west front of the Great Altar of Zeus at Pergamon, p. 152, 5.73 Athena and Alkyoneus, Great Frieze of the Great Altar of Zeus at Pergamon, p. 152, 5.74 Pythokritos of Rhodes (?), Nike of Samothrace, p. 153, 5.75 Aphrodite, Pan, and Eros, p. 154, 5.76 Drunken Old Woman, p. 155, 5.77 Hellenistic Painting Key Images The Abduction of Persephone, detail of a wall painting in Tomb I, Vergina, p. 157, 5.78 The Battle of Issos or Battle of Alexander and the Persians, p. 158, 5.79 The Hellenistic period dates from 323–31 BCE. The period dates from the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE until the defeat of Cleopatra VII by Augustus following the Battle of Actium. Fueled by the philosophy of Aristotle, which emphasized keen observation of nature and a strict empirical approach to the study of the world, sculpture during the Hellenistic period displays a psychological and physical naturalism unparalleled in previous Greek art. 29 Dramatic spatial involvement, dynamic movement, and everyday subject matter also characterize the sculpture of this period. The major centers of Hellenistic art production included Alexandria, founded by Alexander in Egypt in 332 BCE, the island of Rhodes, and Pergamon in Asia Minor. A great deal of our knowledge of Hellenistic painting is based on Roman copies in fresco or in mosaic. In the mosaic copy from Pompeii of the Battle of Alexander and the Persians, we witness a vivid and energetic activity so characteristic of Hellenistic art. In the frieze of the Great Pergamon Altar, we encounter an overt display of emotion with strong dramatic force and an exploding rhythm of the figures. Key Terms/Places/Names meander pattern amphora prothesis belly-handled amphora neck-amphora guilloche pattern cella pronaos peristyle peripteral temple stereobate stylobate entasis Doric column echinus abacus pediment Ionic column kore (plural: korai) kouros (plural: kouroi) Archaic smile peplos chiton himation symposium black-figure vase painting red-figure vase painting Exekias ″Severe Style″ contrapposto lost-wax process 30 symmetria kanon Myron Polykleitos Perikles acropolis chryselephantine Pheidias amazonomachy ratio of proportions Iktinos Kallikrates Praxiteles Polykleitos the Younger Lysippos white-ground lekythos gymnasia Hellenistic realism skiagraphia Discussion Questions 1. Compare and contrast the black-figure style of vase painting with that of the redfigure style in both technique and illusionism in painting. 2. Discuss the term ″Pheidian style″ in relation to the sculpture of the Parthenon. 3. Discuss the development of the human figure in Greek art from the Archaic through the Hellenistic periods. 4. Describe how the subject matter of the Parthenon frieze illustrates the major concerns and values of Athens in the time of Pericles. 5. In what ways is Praxiteles’ Aphrodite of Knidos revolutionary? 6. Discuss the architectural refinements used in the construction of the Parthenon. 7. What was the impact of the lost wax process? 8. What characterizes paintings of the Hellenistic period? Resources Books 31 Arias, Paolo. A History of 1000 Years of Greek Vase Painting. New York: Harry Abrams, 1962. Ashmole, Bernard. Architect and Sculptor in Classical Greece. New York: New York University Press, 1972. Bluemel, Carl. Greek Sculptors at Work, 2nd ed. London: Phaidon Press, 1969. Boardman, John. Greek Art, 4th ed. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1996. Boardman, John. Greek Sculpture: The Archaic Period. A Handbook. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1991. Boardman, John. Greek Sculpture: The Classical Period. A Handbook. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1995. Blundell, Sue. Women in Ancient Greece. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995. Boardman, John. The Parthenon and its Sculptures. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1986. Jenkins, Ian. The Parthenon Frieze. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1994. Keuls, Eva. The Reign of the Phallus: Sexual Politics in Ancient Athens. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993. Lawrence, A. W. and R. A. Tomlinson. Greek Architecture, 5th ed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996. Meiggs, Russell, ed. A Selection of Greek Historical Inscriptions to the End of the Fifth Century B.C. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. Neils, Jenifer. Goddess and Polis: The Panathenaia in Ancient Athens. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992. Neils, Jenifer, ed. The Parthenon: From Antiquity to the Present. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005. Osborne, Robin. Archaic and Classical Greek Art. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998. Pollitt, J. J. Art and Experience in Classical Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1972. Pollitt, J. J. The Art of Greece 1400–31 BC: Sources and Documents. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990. 32 Rasmussen, Tom, and Nigel Spivey, eds. Looking at Greek Vases. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991. Rhodes, Robin. Architecture and Meaning on the Athenian Acropolis. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995. Richter, Gisela. A Handbook of Greek Art. London: Phaidon Press, 1994. Smith, R. R. R. Hellenistic Sculpture. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1991. Spivey, Nigel. Understanding Greek Sculpture: Ancient Meanings, Modern Readings. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1997. Stewart, Andrew. Greek Sculpture: An Exploration. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990. Warden, P. Gregory, ed. Greek Vase Painting: Form, Figure, and Narrative. Dallas: Meadows Museum, SMU Press, 2004. DVDs Ancient Greece: Traditions of Greek Culture. (2004). Kultur Video. 120 min. Ancient Greek Art and Architecture. (2003). Educational Video Network, Inc. 21 min. Ancient Mysteries: Secrets of Delphi. (2006). A & E Home Video. Lost Treasures: Ancient Greece. (1998). 50 min. The Greek Gods. (2004). The History Channel. The Greeks: Crucible of Civilization. (2000). PBS Empires Series. 150 min. www http://ancient-greece.org/ Diotima: Women and Gender in the Ancient World http://www.stoa.org/diotima/ The Ancient City of Athens http://www.stoa.org/athens/ The Perseus Digital Library http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/ Virtual Library of Archaeology (Indiana University) http://archnet.asu.edu/