Flannery O`Connor

advertisement

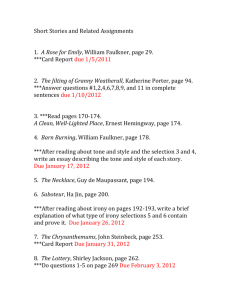

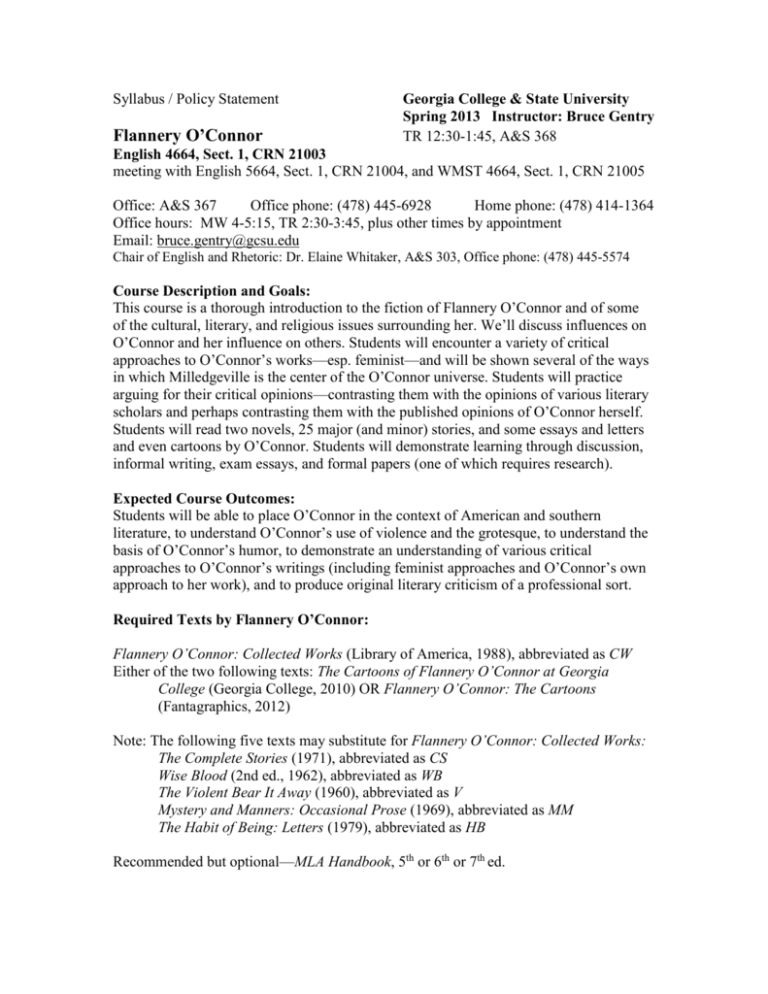

Syllabus / Policy Statement Flannery O’Connor Georgia College & State University Spring 2013 Instructor: Bruce Gentry TR 12:30-1:45, A&S 368 English 4664, Sect. 1, CRN 21003 meeting with English 5664, Sect. 1, CRN 21004, and WMST 4664, Sect. 1, CRN 21005 Office: A&S 367 Office phone: (478) 445-6928 Home phone: (478) 414-1364 Office hours: MW 4-5:15, TR 2:30-3:45, plus other times by appointment Email: bruce.gentry@gcsu.edu Chair of English and Rhetoric: Dr. Elaine Whitaker, A&S 303, Office phone: (478) 445-5574 Course Description and Goals: This course is a thorough introduction to the fiction of Flannery O’Connor and of some of the cultural, literary, and religious issues surrounding her. We’ll discuss influences on O’Connor and her influence on others. Students will encounter a variety of critical approaches to O’Connor’s works—esp. feminist—and will be shown several of the ways in which Milledgeville is the center of the O’Connor universe. Students will practice arguing for their critical opinions—contrasting them with the opinions of various literary scholars and perhaps contrasting them with the published opinions of O’Connor herself. Students will read two novels, 25 major (and minor) stories, and some essays and letters and even cartoons by O’Connor. Students will demonstrate learning through discussion, informal writing, exam essays, and formal papers (one of which requires research). Expected Course Outcomes: Students will be able to place O’Connor in the context of American and southern literature, to understand O’Connor’s use of violence and the grotesque, to understand the basis of O’Connor’s humor, to demonstrate an understanding of various critical approaches to O’Connor’s writings (including feminist approaches and O’Connor’s own approach to her work), and to produce original literary criticism of a professional sort. Required Texts by Flannery O’Connor: Flannery O’Connor: Collected Works (Library of America, 1988), abbreviated as CW Either of the two following texts: The Cartoons of Flannery O’Connor at Georgia College (Georgia College, 2010) OR Flannery O’Connor: The Cartoons (Fantagraphics, 2012) Note: The following five texts may substitute for Flannery O’Connor: Collected Works: The Complete Stories (1971), abbreviated as CS Wise Blood (2nd ed., 1962), abbreviated as WB The Violent Bear It Away (1960), abbreviated as V Mystery and Manners: Occasional Prose (1969), abbreviated as MM The Habit of Being: Letters (1979), abbreviated as HB Recommended but optional—MLA Handbook, 5th or 6th or 7th ed. Conferences: I invite you to meet with me outside class to discuss your writing. Let me know when you want to have a conference at a time other than my usual office hours; you will usually find a sign-up sheet for conferences posted on my office door. What we talk about in conference is usually up to you. You may leave messages on my phones or on my email. I respond as promptly as possible. You will generally receive 1-3 points extra credit for a substantial writing conference in my office, once each week (M-F). (See explanation of grading system on the pages that follow.) A bit of info about me: I’m married to the poet Alice Friman. I was born in Little Rock, AR, in 1953. BA in English and Journalism from Arkansas-Fayetteville; MA in English from Chicago; PhD in English from Texas-Austin. I taught at Texas, Texas A&M, and Indianapolis before coming to GCSU in 2003. I’m Editor of the Flannery O’Connor Review, so don’t be surprised when you see other people in my office, at work on the Review. Writing Center: You will generally receive 2 points of extra credit for a writing conference in the GCSU Writing Center, once per week (M-F). Several experienced tutors are waiting for you to walk in and ask for their assistance and encouragement. Any tutors taking this course may consult with other tutors. Please have the tutor write you a note about the conference, and deliver the note to me at our next class meeting to get your extra credit points—that’s the only way to guarantee credit. Grading Scale: 1000 total points possible. GCSU does not record + and - on final grades, but I record them in my grade book and remember them—when I write recommendation letters, etc. A = 920-1000 (92% or more); A- 900-919; B+ 860-899; B 830-859; B- 800-829; C+ 760799; C 730-759; C- 700-729; D+ 660-699; D 630-659; D- 600-629; F 599 or fewer pts. Course Assignments and Point Values: TOTAL POSSIBLE 1,000 exam on novels (800 words min.) 100 points short, unresearched paper on an early story (editing draft, graded draft, revision) 1500 words min. for undergrad students 150 points research paper, on a novel or on a late story (editing draft, graded draft, revision) 3000 words min. for undergrad students—6 sec. sources 300 points daily work: responses and other homework, editing, in-class exercises (approx. 2500 words) 300 points final exam on stories (1350 words min.) 150 points Extra Credit: You may receive up to 40 extra credit points, for conferences, Writing Center visits, your top 3 extra homework responses to the assigned readings (1/2-3 points each), responses to film versions of assigned works or O’Connor-related films, responses to special events like the February lecture series at Andalusia (each Sunday afternoon at 3 pm) or volunteer work at Andalusia. Maximum extra credit for a response to a two-hour film or for a response to a special event of 2 hours or for a 3-hour stint as an Andalusia volunteer is 10 points. Extra credit used to make up for a late first exam or lateness on the two major papers or for excessive absence does not count toward the max. of 40. Revisions: You may revise the first exam and either or both of the two out-of-class papers after they are first graded. The schedule lists dates when one revision per student will be accepted: Feb. 21, Mar. 19, Apr. 18, Apr. 23, Apr. 25, and at the beginning of your final exam. When you submit a revision, also turn in the previously graded version (along with the grading sheet and any necessary photocopies of secondary sources regarding the research paper), and attach a note to the revision describing the improvements you want me to notice: a “Brag Sheet.” Your grade on a revision cannot be lower than the grade assigned to it the first time. I average the original grade with the best revision grade to arrive at the final grade for a given paper. Papers submitted without brag sheets and papers that miraculously appear in my email (I don’t want email for formal submissions.) are penalized one point. Policies on daily grades: Homework must be made up. Editing on Feb. 21, Mar. 21, and Apr. 16 may sometimes (and should) be made up. I can drop one editing grade if you have absence time to spare. On the other hand, you are required to have at least one editing grade, even if it is a zero on top of an absence. You are counted present during editing time if, and only if, you participate in editing. In-class exercises may not be made up, but they do not count if you are not in class. They may not be turned in after the end of the class meeting in which they are assigned. Checks as grades: Any work that receives a check-plus raises your point total by one point; a check-minus costs you one point, and so on; assignments graded with checks for some students may also receive percentile grades for others, including 0%. Participation helps generally and affects homework response grades. Special notes on homework responses: A response page is a single sheet of paper on the front and back of which you have recorded your most controversial and interesting and outrageous ideas about all of a class meeting’s assigned readings. Note what is peculiar about a work and try to account for it. Ask impossible questions and then take a stab at answering them. Talk about symbolism. You should also write and underline a statement of your overall interpretation of each novel and story. The goal is to prepare for good class discussion. Think of your response as a list of ideas, which do not have to be connected to each other. Try to notice the differences among O’Connor’s works. Responses are due at the very beginning of class on the day the reading is to be discussed, and you must discuss your response in class to receive full credit. I call on some or all of the people who have written responses to begin the day’s discussion. Another requirement for each response page is that you record and respond to, in three or four sentences, probably, what one critical study of O’Connor (preferably from our reserve list) has to say about at least one of the day’s assigned works. (Sometimes I assign a reading to take the place of a critical reading; most of the time, you should pick critical selections to help you prepare for the research paper. Don’t use the same critical piece for two responses.) Include a works cited entry for your critical source, and give me a printout of any computer-generated source you use for your response when you submit the response. The big idea here is for us to discuss critical approaches regularly. Record something interesting, but don’t let a critic’s views take over your response. Undergraduate students are required to submit 7 homework responses; if a student submits more, I count the best grades (but at least 1 in each calendar month, and at least 2 by Feb. 19 for assignments through Feb. 19). You also earn extra credit for the 4 best additional responses. Extra credit for extra responses is awarded as follows: 3 points for A, 2 points for B, 1 point for C, ½ point for D or F. (There are 25 response opportunities, Jan. 10-Apr. 25.) Incomplete or late responses receive low grades and therefore usually turn into extra credit. I give feedback on responses primarily by underlining the best ideas I find on the response. I grade responses primarily on the basis of the number of ideas. I also take account of the originality and controversiality of the ideas, and my grading of responses is often affected by the quality of your overall interpretation and by my sense of how well class discussion goes. It’s okay to turn in a response just to see what kind of feedback you get, because not all of your responses have to affect your final course grade. Early submission of responses: if you provide, in time for the class meeting before a given response is due, photocopies sufficient for everyone to see what you have to say about the next reading assignment, you do not need to be present the day the reading is assigned in order to get full credit for the response. Combining response grades: If you turn in only half or a third of a response, it won’t get a very good grade, but I’m willing, one time, to combine two partial response page grades into one grade with a maximum resulting grade of 79%. Writing responses to events, films, volunteer work for extra credit: Tell me how long the thing you are responding to lasted, and then write the usual sort of response. If you know that I have not witnessed the extra credit item, give a summary of what you are responding to. These extra credit responses do not pick up points as quickly as homework responses earn points, but they can indeed be grade-savers. If the teacher is absent: If for some reason I should suddenly be unable to attend a scheduled class, here’s the plan for the various sorts of class meetings: the novel exam will be rescheduled or I will arrange for someone else to conduct the exam. Editing sessions will proceed in my absence as scheduled, with paperwork submitted under my office door by the end of class. On dates when we are discussing responses to assigned readings, if I am absent, you may still consider it possible to submit a homework response page under my door, but it is also the case that everyone else who wants to be counted present for that class (or portion of class) must submit a response page for that class by the end of the class period; I’ll count such a response as homework if that helps, as an in-class exercise grade if that is better for you. Attendance: After you have three full class periods’ worth of absence time, points are subtracted from your point total. I do not “excuse” absences. Each additional absence lowers your grade 2 points for each 5 minutes of absence, with a max. of 30 points for an entire class meeting. (Note: Extra credit work can eliminate this point penalty.) After I have learned names, I usually take roll by passing around an attendance sheet, so make sure you sign in each day. Please notify me in writing or by phone message when you know you are going to be absent. Unconsciousness counts as absence. Partial absence counts as absence. Late work: If you have to turn work in late, please notify me in writing or by phone message. In general, I penalize late major papers 3 points per weekday late. You may turn in two papers a day late without penalty, or one paper two days late, without penalty. Grades on late daily work are generally no higher than D+ or check-minus. Seriously late work— major paper or daily work—may have its credit cut in half. Don’t submit late revisions. Special needs: Any special needs will be accommodated when they are properly documented. Students with learning disabilities or special needs are urged to contact me early in the semester in order to secure the best possible learning environment. If you have a disability as described by the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Section 504, you may be eligible to receive accommodations to assist in programmatic and physical accessibility. Disability Services, a unit of the GCSU Office of Institutional Equity and Diversity, can assist you in formulating a reasonable accommodation plan and in providing support in developing appropriate accommodations to ensure equal access to all GCSU programs and facilities. Course requirements will not be waived, but accommodations may assist you in meeting the requirements. For documentation requirements and for additional information, we recommend that you contact Disability Services at (478) 445-5931 or (478) 445-4233. Plagiarism and other illegal behaviors: Plagiarism is presenting someone else’s words or ideas as your own, in writing or speaking. You are engaging in illegal behavior if you present another’s ideas as your own without citing the source; paraphrase without citing the source; paraphrase improperly; use direct quotations without quotation marks; use direct quotations without citing the source; submit material written by someone else as your own; submit work for which you have received so much help that the writing is different from your own; copy assignments previously submitted by another student. These and other illegal behaviors can result in failing an assignment, failing a course, even being expelled from college. Please make sure, through questions in class or conferences in my office, that you understand how to produce your academic work legally. All students are expected to abide by the requirements of the Georgia College Honor Code as it applies to all academic work. Failure to do so will result in serious penalties. The instructor has the right to require your papers in a form suitable to submit them to plagiarism detection services. Fire Drill: In case of a fire or fire drill—and I’m told we should expect at least one—take the nearest stairs, not the elevator. Crawl on the floor if you encounter heavy smoke. Learn the floor plan and exits of the A&S Building. Assist disabled persons and others if possible without endangering your own life. Get out of the building (in a quick, orderly fashion) and meet me on the lawn in front of Terrell Hall (on the front lawn), where I will calmly check students off my class roll as present and accounted for. Titles I have asked to be put on reserve for this course (almost listed in MLA style): Douay-Rheims version of the Bible (O’Connor’s preferred version) The Flannery O’Connor Bulletin and the Flannery O’Connor Review, with index to vol. 1-15 of Bulletin. Asals, Frederick. Flannery O’Connor: The Imagination of Extremity. Georgia, 1982. Bacon, Jon Lance. Flannery O’Connor and Cold War Culture. Cambridge, 1993. NR Baumgaertner, Jill P. Flannery O'Connor: A Proper Scaring. Cornerstone, 1998. R Bloom, Harold, ed. Modern Critical Views: Flannery O’Connor. Chelsea, 1988. Brinkmeyer, Robert H., Jr. The Art and Vision of Flannery O’Connor. LSU, 1989. Browning, Preston M., Jr. Flannery O’Connor. Southern Illinois, 1974. Caruso, Teresa, ed. “On the Subject of the Feminist Business”: Re-reading Flannery O’Connor. Lang, 2004. F Cash, Jean W. Flannery O’Connor: A Life. Tennessee, 2002. Note: a full-length biography. Ciuba, Gary M. Desire, Violence, and Divinity in Modern Southern Fiction: Katherine Anne Porter, Flannery O’Connor, Cormac McCarthy, Walker Percy. LSU, 2007. Chapter on TVBIA. Desmond, John F. Risen Sons: Flannery O’Connor’s Vision of History. Georgia, 1987. R Di Renzo, Anthony. American Gargoyles: Flannery O’Connor and the Medieval Grotesque. Southern Illinois, 1993. Edmondson, Henry T., III. Return to Good and Evil: Flannery O’Connor’s Response to Nihilism. Lexington, 2002. GCSU faculty. Eggenschwiler, David. The Christian Humanism of Flannery O'Connor. Wayne State, 1972. R Elie, Paul. The Life You Save May Be Your Own: An American Pilgrimage. Farrar, 2003. A biography of O’Connor in relation to three other Catholic writers. Farmer, David. Flannery O’Connor: A Descriptive Bibliography. Garland, 1981. A bibliography of O’Connor’s works. Feeley, Kathleen, S.S.N.D. Flannery O’Connor: Voice of the Peacock. Fordham, 1982. R, recently reprinted. Friedman, Melvin J., and Lewis A. Lawson, eds. The Added Dimension: The Art and Mind of Flannery O’Connor. Fordham, 1977. ---, and Beverly Lyon Clark, eds. Critical Essays on Flannery O’Connor. Hall, 1985. Gentry, [Marshall] Bruce and Craig Amason. At Home with Flannery O’Connor: An Oral History. Interviews with people who knew O’Connor. Andalusia, 2012. Gentry, Marshall Bruce. Flannery O’Connor’s Religion of the Grotesque. Mississippi, 1986. Giannone, Richard. Flannery O’Connor and the Mystery of Love. Fordham, 1999. R ---. Flannery O’Connor, Hermit Novelist. Illinois, 2000. R Gooch, Brad. Flannery: A Life of Flannery O’Connor. Little, 2009. A full-length biography. Gordon, Sarah. Flannery O’Connor: The Obedient Imagination. Georgia, 2000. Former GCSU faculty. F ---, with Craig Amason and Marcelina Martin. A Literary Guide to Flannery O’Connor’s Georgia. Georgia, 2008. Gretlund, Jan Nordby, and Karl-Heinz Westarp, eds. Flannery O’Connor’s Radical Reality. South Carolina, 2006. Han, John J., ed. Wise Blood: A Re-Consideration. Rodopi, 2011. Hardy, Donald E. The Body in Flannery O’Connor’s Fiction. South Carolina, 2007. NR ---. Narrating Knowledge in Flannery O’Connor’s Fiction. South Carolina, 2003. NR Hendin, Josephine. The World of Flannery O’Connor. Indiana, 1970. NR/F, recently reprinted Hewitt, Avis, and Robert Donahoo, eds. Flannery O’Connor in the Age of Terrorism. Tennessee, 2010. Johansen, Ruthann Knechel. The Narrative Secret of Flannery O’Connor. Alabama, 1994. Kilcourse, George A., Jr. Flannery O’Connor’s Religious Imagination: A World with Everything Off Balance. Paulist, 2001. Introductory. R Kinney, Arthur F. Flannery O’Connor’s Library: Resources of Being. Georgia, 1985. Describes O’Connor’s library, her reactions to her reading. Kreyling, Michael, ed. New Essays on Wise Blood. Cambridge, 1995. Lake, Christina Bieber. The Incarnational Art of Flannery O’Connor. Mercer, 2005. R/F McFarland, Dorothy Tuck. Flannery O’Connor. Ungar, 1976. McMullen, Joanne Halleran. Writing Against God: Language as Message in the Literature of Flannery O’Connor. Mercer, 1996. ---, and Jon Parrish Peede, eds. Inside the Church of Flannery O’Connor: Sacrament, Sacramental, and the Sacred in Her Fiction. Mercer, 2007. Martin, Carter. The True Country: Themes in the Fiction of Flannery O’Connor. Vanderbilt, 1968. R May, Charles E., ed. Flannery O’Connor: Critical Insights. Salem, 2011. May, John R. The Pruning Word: The Parables of Flannery O'Connor. Notre Dame, 1976. R Muller, Gilbert H. Nightmares and Visions: Flannery O’Connor and the Catholic Grotesque. Georgia, 1972. R Nisly, L. Lamar. Wingless Chickens, Bayou Catholics, and Pilgrim Wayfarers: Constructions of Audience and Tone in O’Connor, Gautreaux, and Percy. Mercer, 2011. O’Connor, Flannery. The Cartoons of Flannery O’Connor at Georgia College. Georgia College, 2010. ---. Conversations with Flannery O’Connor. Ed. Rosemary Magee. Mississippi, 1987. Interviews. ---. Flannery O’Connor: The Cartoons. Ed. Kelly Gerald. Fantagraphics, 2012. ---. The Habit of Being: Letters of Flannery O’Connor. Ed. Sally Fitzgerald. Farrar, 1979. Contains letters not in the Library of America’s CW. ---. Mystery and Manners: Occasional Prose. Ed. Sally and Robert Fitzgerald. Farrar, 1969. Contains essays not in CW. See esp. “On Her Own Work.” ---. The Presence of Grace and Other Book Reviews. Comp. Leo Zuber. Ed. Carter W. Martin. Georgia, 1983. O’Gorman, Farrell. Peculiar Crossroads: Flannery O’Connor, Walker Percy, and Catholic Vision in Postwar Southern Fiction. LSU, 2004. R Orvell, Miles. Flannery O’Connor: An Introduction. Mississippi, 1991. Paulson, Suzanne Morrow. Flannery O’Connor: A Study of the Short Fiction. Twayne, 1988. Piper, Wendy. Misfits and Marble Fauns: Religion and Romance in Hawthorne and O’Connor. Mercer, 2011. R Prown, Katherine Hemple. Revising Flannery O’Connor: Southern Literary Culture and the Problem of Female Authorship. Virginia, 2001. NR/F Ragen, Brian Abel. A Wreck on the Road to Damascus: Innocence, Guilt, and Conversion in Flannery O’Connor. Loyola, 1989. R Rath, Sura, and Mary Neff Shaw, eds. Flannery O’Connor: New Perspectives. Georgia, 1995. Robillard, Douglas, Jr. The Critical Response to Flannery O’Connor. Praeger, 2004. A large collection of articles, arranged chronologically. Sharp, Jolly Kay. Between the House and the Chicken Yard: The Masks of Flannery O’Connor. Mercer, 2012. F Seel, Cynthia L. Ritual Performance in the Fiction of Flannery O’Connor. Camden, 2001. F Scott, R. Neil. Flannery O’Connor: An Annotated Reference Guide to Criticism. Timberlane, 2002. A nearly comprehensive guide to criticism about O’Connor, 1972-2000. Everyone should browse. ---, and Valerie Nye, comp., Sarah Gordon and Irwin Streight, eds. Postmarked Milledgeville: A Guide to Flannery O’Connor’s Correspondence in Libraries and Archives. GCSU, 2002. Sharp, Jolly Kay. “Between the House and the Chicken Yard”: The Masks of Mary Flannery O’Connor. Mercer, 2011. R Shenandoah: The Washington and Lee University Review, 60th Anniverary Issue. 60.1-2 (2010). Essays, poems, stories in response/tribute to O’Connor. Shloss, Carol. Flannery O’Connor’s Dark Comedies: The Limits of Inference. LSU, 1980. (Also available from LSU as a recent reprint) NR Spivey, Ted R. Flannery O’Connor: The Woman, the Thinker, the Visionary. Mercer, 1995. Srigley, Susan. Flannery O’Connor’s Sacramental Art. Notre Dame, 2004. R Stephens, Martha. The Question of Flannery O’Connor. LSU, 1973. NR Sykes, John D., Jr. Flannery O’Connor, Walker Percy, and the Aesthetic of Revelation. Missouri, 2007. R Walters, Dorothy. Flannery O’Connor. Twayne, 1973. Introductory. Watkins, Steven R. Flannery O’Connor and Teilhard de Chardin. Peter Lang, 2009. Westarp, Karl-Heinz, comp. Flannery O’Connor: The Growing Craft. Summa, 1993. Drafts of the various stories that ended up as “Judgment Day.” Westling, Louise. Sacred Groves and Ravaged Gardens: The Fiction of Eudora Welty, Carson McCullers, and Flannery O’Connor. Georgia, 1985. F Whitt, Margaret. Understanding Flannery O’Connor. South Carolina, 1995. Introductory. Wood, Ralph. Flannery O’Connor and the Christ-Haunted South. Eerdmans, 2004. R Yaeger, Patricia. Dirt and Desire: Reconstructing Southern Women's Writing, 1930-1990. Chicago, 2000. Good for linking O’Connor to other southern women writers. NR/F Note: These items on reserve may be checked out for a week at a time. Please do not check out more than 6 reserve items at the same time. R = generally a religious approach NR = generally not a religious approach F = feminist approach Tentative and Partial Schedule [Dates when class doesn’t meet are in brackets.] Jan. 8 introduction to course, show and tell by the prof., visit by Craig Amason of Andalusia Jan. 10 “The Crop” (early story) and “The Enduring Chill” (late story) As criticism, read Chronology in CW or Giroux intro to CS. Jan. 15 “A Late Encounter with the Enemy” (early) and an O’Connor cartoon book As criticism, read Gordon essay or Gerald essay in a cartoon book. Jan. 17 Wise Blood, chapters 1-7 Jan. 22 Wise Blood, chapters 8-14 Jan. 24 The Violent Bear It Away, chapters 1-3 Jan. 29 The Violent Bear It Away, chapters 4-12 in-class exercise on exam questions Jan. 31 “The Barber” (early) and “The Lame Shall Enter First” (late) I’ll distribute exam sheet. Feb. 5 “An Afternoon in the Woods” OR “The Turkey” (early) and “The River” (early) as crit: “Introduction to A Memoir of Mary Ann” in CW or MM Feb. 7 novel exam Feb. 12 “A Circle in the Fire” (early) Feb. 14 “A Stroke of Good Fortune” (early) I’ll return the novel exam. Feb. 19 “The Displaced Person” (early) and, as criticism, essay “The King of the Birds” Note: Patrick Samway, S.J., presents the Flannery O’Connor Memorial Lecture at 7:30 p.m. in the Museum Education Room of the Library. A response to this event may count as both an extra credit response and as criticism for the Feb. 26 homework response. Feb. 21 editing session on short paper about an early story I’ll be away at a conference; you may edit in class or outside class, remember. one revision accepted cutoff date for midterm grades Feb. 26 “A View of the Woods” (late) midterm grades submitted by today Feb. 28 “A Temple of the Holy Ghost” (early) explanation of midterm grades Mar. 5 “Greenleaf” (late) short paper due with Feb. 21 editing paperwork Mar. 7 “The Comforts of Home” (late) Mar. 12 “Everything That Rises Must Converge” (late) I’ll return short paper. Mar. 14 “Parker’s Back” (late) Mar. 19 “Revelation” (late) working bibliography homework due one revision accepted Mar. 21 editing session on research paper I’ll return working bibliography homework. I’ll return Mar. 19 revisions. [Mar. 25] Flannery O’Connor’s 88th birthday [Mar. 26, 28] no class – spring break Apr. 2 “Wildcat” (early) and “The Artificial Nigger” (early) Apr. 4 “The Life You Save May Be Your Own” (early) research paper due Apr. 9 “The Geranium” (early) and “Judg[e]ment Day” (late) Apr. 11 “The Partridge Festival” (late) recommended criticism: FLOCR’s vol. 9 articles on Pete Dexter and Paris Trout I’ll return the research paper with Mar. 19 editing paperwork. Apr. 16 editing session for revisions Apr. 18 “Good Country People” (early) Homework: Submit 15 final exam essay questions, each about a different story. one revision accepted Apr. 23 “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” (early) one revision accepted I’ll distribute the final exam prep sheet. Apr. 25 35 pages of O’Connor’s letters/essays not previously read as criticism. evaluation of readings for course The beginning of this class is the deadline for extra credit other than makeup. one revision accepted Wed., May 1 10:30 am -12:45 pm Final exam, on stories not used for papers (Final may also be taken Tues., Apr. 30, 6-8:15 pm, if you sign up for that time.) The beginning of your final exam period is the deadline to submit extra credit as absence/lateness makeup. one revision accepted at beginning of your final Apr. 16 editing paperwork is due at the beginning of your final. Notes on the final and what happens after the course: I’ll return the last two sets of revisions after the course ends. Drop by next fall. Give me an SASE with one ounce worth of postage to get your grade. Give me an SASE with two ounces of postage to get your grade and final exam. I’ll retain unmailed finals for a year; you may pick them up the following regular semester. I do not discuss the specifics of final grades via email; write me a letter. Major Paper Assignments Flannery O’Connor English 5/4664, WMST 4664 Bruce Gentry Georgia College Spring 2013 Basic assignment both for the exams and the formal papers: In the intro, you will describe the issue you are going to discuss and explain why it is debatable. (Your sense of opposing views should come from your own brainstorming or from class discussion or, for the research paper, from your research.) Then you will state your thesis and map out briefly how you will argue for your thesis. Emphasize your controversiality and originality. In the body, you will want to provide a series of paragraphs, almost always starting with a topic sentence, in which you provide evidence for your thesis. Base your argument on evidence from the text, and provide parenthetical page references for specific evidence. As necessary, analyze the evidence. Also, make sure that as often as it helps, you refute the best opposing arguments. You may find that if you explain briefly the reasoning behind opposing views, it is easier to explain where your opposition went wrong. Refutation is another opportunity to present evidence for your thesis (once you provide the proper analysis). Explain how you differ from critics quite different from you, but also try to distinguish your arguments from those of people who basically agree with you. In the conclusion, discuss the big picture. What does the lit work mean overall, now that you’ve proven your thesis to be true? How’s the work you are analyzing different from the rest of O’Connor’s works? You might find that in order to make the significance of your argument apparent, you will need to explain what your worthy opposition thinks the work means. Schedule for Research Paper: Anytime: conferences on papers, problems, working biblio/Works Cited list Mar. 19 working bibliography homework due Mar. 21 edit Research Paper Apr. 4 Research Paper due with editing paperwork from Mar. 21 Apr. 11 return of graded Research Papers Apr. 16 editing session for revisions Apr. 18, 23, revision of Research Paper accepted OR revision of another paper 25, start of your final Working Bibliography: At any time, you may turn in a list of primary and secondary sources written up in MLA style. I’ll happily assess your progress in completing your Works Cited page properly. You may also include the primary source as an extra entry, for practice. Grad students and WMST students might also include in the working bibliography any theoretical works that are likely to guide the critical approach used in the paper. I’ll return marked bibliographies at the class after you give them to me. Undergraduates need a list of at least 8 secondary sources, and they may work together and submit a single working bibliography. Graduate students need at least 10 secondary sources. All working bibliographies should include entries for the required secondary sources by O’Connor (two, from letters, essays, interviews, book reviews, cartoons). Special requirements for research paper: Topic: This paper may be written about any of assigned stories by O’Connor with the “late” label, or either of the novels. The research you do should help you write the part of the intro in which you present the “problem”: your explanation of a debate to which your paper responds. It may make sense to discuss all of your critical sources briefly in the opening paragraph, although that is not required. Your goal is to present an original argument for your own original thesis on an interpretive controversy surrounding the work you have selected. You want to demonstrate that you have developed a good sense of what sorts of things have been said by critics about your topic, and then you want to make a good case for your view as superior. If there is a raging controversy between gangs of critics, show you know about both sides. You also need to report on two different sources in which O’Connor gives some indication of her opinions about the work and/or the subject matter you are discussing. Most of you will use CW or MM and HB. Some of you may want to use other published letters and some of you may want to use O’Connor’s interviews, her book reviews, her cartoons. (Note: Indirect sources for O’Connor receive almost no credit; find the right version of the source.) In the body of the paper, you should argue for your interpretive thesis about the work. You may wish to refer occasionally to critical sources in the body of the text (to refute them, and/or to remind me of your originality), but basically, in the body of the text, you are to base your argument on evidence from the literary text your paper is discussing. When you bring up opposing critics, demonstrate that you understand their reasoning and show why you don’t accept it. When you bring up critics who agree with you, try to show how your views are more than just a repeat of what others have said. Do not slavishly agree with any critic. The conclusion relates your thesis to your overall interpretation of the work and argues for the superiority of your overall interpretation to the interpretations you have found in any criticism you have read. It is reasonable to discuss what the critics you have read imply that a given work means, even if they don’t come right out and clearly state an overall interpretation. Have you revealed anything about the work that would surprise or irritate Flannery O’Connor herself? Minimum length and secondary sources: UG: 3000 words of text—not counting WC page—with 2 secondary sources by O’Connor and 4 secondary sources by others and 1 primary source by O’Connor Grad students: 4500 words of text—not counting WC page—with 2 secondary sources by O’Connor and 6 secondary sources by others and 1 primary source by O’Connor You will need to use MLA style. It should not matter which recent edition of the MLA Handbook you consult. Along with your paper and WC page, you should turn in photocopies to demonstrate your scholarly use of all of your critical sources (except for those written by O’Connor). Write on each photocopy your name and the critic’s name, clearly label each passage from which you have borrowed ideas or words, and make sure the page number appears on each photocopy. The checklist on the final page of this handout reviews things you need in your paper. You may use a computer-generated source if it is a reprint of a previously published, scholarly publication; if you use such a computer-generated source, give me a photocopy of the entire work, and in your WC entry, provide complete bibliographic information about the work’s original publication before you provide the following at the end of the entry: computer source, date of access, and newly assigned page numbers (starting with 1). Note: This is my one requirement that departs from MLA guidelines a bit. Exception to the departure: If you are using a pdf file (a computer generated photograph of a source) you need not give me the entire source and you need not renumber pages starting with 1. If the requirement of photocopies seems a burden, write a research paper based entirely on published books and submit with your paper the books you used; use post-its to identify the passages you have quoted/paraphrased. I’ll return within seven days any books you give me. My usual procedure in grading a research paper: First I read the text of the paper and determine for myself a grade for the paper's basic argument. Then I check the parenthetical documentation, the Works Cited list, and the photocopies. If fewer than the required number of secondary critical sources are properly used, the grade drops substantially. Weak grammar can also substantially lower the grade on a paper that is otherwise very strong. Point: Consistently exceed minimum standards, or be very very careful. I often give partial credit for the use of use of a source even when the use is not entirely accurate. Here is a scale of the maximum grades I allow myself to give to papers with certain numbers of source credits. Grad students 89% 7 1/3 source credits 86% 7 66% 3 2/3 84% 6 2/3 64% 3 1/3 82% 6 1/3 62% 3 80% 6 60% 2 2/3 78% 5 2/3 58% 2 1/3 76% 5 1/3 56% 2 74% 5 53% 1 2/3 72% 4 2/3 50% 1 1/3 70% 4 1/3 45% 1 68% 4 40% 2/3 35% 1/3 30% 0 Undergrad students (ENGL or WMST) 89% 5 1/3 88% 5 65% 2 1/3 86% 4 2/3 59% 2 83% 4 1/3 56% 1 2/3 80% 4 53% 1 1/3 77% 3 2/3 50% 1 74% 3 1/3 45% 2/3 71% 3 40% 1/3 68% 2 2/3 30% 0 Note: The research paper must be typed or it will receive zero credit. How to edit Flannery O’Connor Gentry, Spr. 2013 Basic assignment, for Feb. 21 and Mar. 21: Bring two or more copies of a draft of your paper (at least 1000 words on Feb. 21, at least 2000 words on Mar. 21). Your job in class on editing day (or out of class, if you can arrange it) is to have your paper edited by at least three classmates and to edit papers by three of your classmates. Note: If your draft is short, it can hurt your editing grade and the grades of others. Before or during or after each editing session, you may give me an introductory paragraph so that I can comment on it and give it back to you before your paper is due. This is entirely optional. (If I have time, I will also happily read additional parts of drafts or full drafts.) Give your copies of your drafts to classmates. It is okay for a copy of a draft to be edited by more than one person. Each copy you bring should be edited by at least one person. You may write on the top of your drafts some specific requests for help. To edit a paper, first read the whole thing through, noticing specific suggestions you can make. Then give advice for improvement: additional specific evidence the author could use, opposing arguments and how to refute them, how to discuss overall interpretations in the conclusion. Write your initials beside each specific suggestion on the face of the paper for which you want credit. If you are editing a paper that has been edited before, you may comment also on the previous editor’s comments. Then write a paragraph of advice at the end or on the back of the paper emphasizing how the author can improve the paper, and sign your full name to the paragraph. What are the paper’s strengths, and more importantly, what should the author add or change? Your job is to help your classmate earn a better grade. It’s appropriate to be much more specific than the teacher is with his assessment comments. You may write sentences you think the author should consider inserting. Whenever you realize one of the drafts you are editing is short of the required length for an editing draft, go ahead and finish editing it, but label it as short on the editing report (see next paragraph) that you submit. Then edit another extra (full-length) draft. When you finish editing three full-length papers, write me an editing report: Give me the names of the people whose papers you edited, and give me the names of the people who edited your paper. If any of the drafts are short and should be considered extra credit, say so. Finally, read over the comments that classmates have written on your paper and add to your report your response to their editing comments: What did you get out of the exercise? Who was helpful, and how? What advice do you disagree with, and why? I use editing reports as my guide as I grade editing, so they need to be complete and accurate. At the end of an editing class, I generally keep a set of editing reports, but you will keep your drafts that classmates have marked as well as anything I’ve commented upon. When you turn in a paper for a grade, also turn in the copies of editing drafts. And if you have done any editing after our editing session, or if you have had more drafts edited, give me a supplementary editing report. I want to make sure everybody gets credit for all of their work. Grades: I count everything when I grade editing: how many copies of drafts you provide, how complete the drafts are, how good an introductory paragraph you’ve shown me is (if that helps), how helpful the comments are that you give to others, how accurate and complete and thoughtful your editing report is, whether everything is turned in on time, etc. If you lose any of the papers relating to editing, or submit work late, your grade may suffer and your editors’ grades may suffer, so be careful. Apr. 16 editing session for revisions: Bring two clean and complete copies of a paper or two that you might revise. I’ll give you special instructions for completing this editing session when the time comes. Research paper checklist / Gentry name_____________________________ Introduction: Is a critical issue clearly presented? Is a good thesis clear early? Is the argument sufficiently mapped? Is it clear that this is a paper about the author’s opinions more than the opinions of previous critics? Rhetoric: Is the thesis significant, original, startling? Does a knowledgeable audience exist for the thesis? Are an audience’s objections and opposing arguments anticipated, discussed, refuted? Does the author distance the paper from the details of similar papers by critics who basically agree with the paper’s argument? Structure: Are there good topic sentences? Do topics begin paragraphs? Are transitions between adjoining parts clear? Evidence from literary text: Are there ample specific references to the story itself in support of claims? Does each piece of evidence have at least one related page reference? Is the evidence sufficiently analyzed? Critical sources: Are the 2 required secondary sources by O’Connor used properly? Are required critical sources by others used properly? (Grads need 6; UGs need 4.) How many source credits does the paper earn, counting partial credits? Are they good sources? Are computer-generated sources previously published, as required? Documentation: Do quotations have quotation marks? Is paraphrasing good, without quotation marks? Is parenthetical documentation complete and accurate? Is the Works Cited page in the proper form? Is all the required publication info included? Is original publication info included when that’s required? Is the literary text included on the Works Cited page? Are there sufficient photocopies of secondary sources, properly marked (your name, critic’s name, passage used, page number)? (Remember that you need at least one photocopy from each secondary source not by O’Connor, and you need complete copies of computer-generated reprints.) Do WC entries for computer-generated sources end with the web source, date of printout, and newly assigned page numbers, starting with 1, as required? Do WC entries for excerpt sources provide complete original publication information before the reprint info, as required? Style, form, and format: Are quotations and paraphrased introduced elegantly? Is quoting accurate? Are key terms and diction in general clear enough? Is the main text of the paper long enough? (Grads 4500, UGs 3000 words) Grammar/mechanics okay? Is the paper typed in MLA format? Overall comments: