How do we meet Dickens today.doc

advertisement

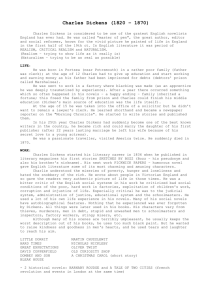

Jørgen Riber Christensen How do we meet Dickens today? In 1992 Brian Henson made The Muppet Christmas Carol based on Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. The Muppets cast consisted of puppets. The only human actor was Michael Caine as Scrooge. This is ironical, as Scrooge is best known in the form of a comic-strip duck: Disney’s Scrooge McDuck, a figure also based on Dickens’ Scrooge. We can infer three things from these two uses of Dickens’ texts. First, Dickens is still productive and is still being used. He is modern; secondly Dickens is widespread, so to speak. He and his texts can be found in the most unlikely contexts; and thirdly, Dickens is unstable with regard to form. His texts may put on the most surprising guises. Dickens was a novelist who wrote rather long novels around 150 years ago, and he is the epitome of a Victorian author. Yet Dickens is also modern. He may be considered as the first modern writer because his subject was urban man and his setting was the modern metropolis, London. Also, Dickens' audience was a mass audience, and not just a segment of the public. Our culture is almost saturated with Dickens. His novels are always in print, they are adapted for film and television again and again, but most significantly it seems to be impossible to read Dickens for the first time. It is as if one comes back to Dickens even at a first reading. It is as if Dickens’ plots and characters are already known. This is caused by the fact that Dickens’ texts have become culture texts. Dickens’ characters have become part of Western popular mythology. Oliver Twist asking for more has become a cultural archetype or stereotype, and our historical conception of the Victorian period is very much based on Dickens’ fictional world. How do we meet Dickens today? Probably our first contact with Dickens will be through his texts as culture texts. But from then on we may meet Dickens in a variety of forms. There are of course the novels in book form, or film adaptations, or television series. These may again be faithful, literary renderings in the BBC tradition, they may be modernized and set in the present, or they may be musicals or Disney cartoons. Also, postmodern pastiches are produced within the serious literary field. There is also - not unimportantly - the whole academic complex of academic Dickens research, published in books, periodicals or on the Internet. All these versions of Dickens are basically a manifestation of the problem of narrative form: How are Dickens’ stories best told? What narrative genre do they belong to? Are they novels, or are their structures too loose to fit into the novel genre? Is Dickens’ production part of highbrow or lowbrow culture? Dickens was the first mass-circulation author, and as such he cannot easily be placed within the hierarchy of taste. Dickens’ work is elusive because it all the time pops out of its textual embodiment: it becomes mythology, ideology, adaptation and reappropriation. George Orwell remarked in his essay ‘Charles Dickens’ (in Inside the Whale, 1940) that “Dickens is one of those writers who are well worth stealing”, but we cannot say that it is the market, or capitalist media interests that have corrupted the original works of Dickens. He himself was the first entrepreneur in the Dickens industry. He marketed his own image as well as his products through public reading tours. He reissued his works in various forms: instalments, parts of magazines (which were his own), one-volume form, three-volume form, and sometimes as 1 plays. Dickens took a strong interest in copyright issues. The marketplace is in other words an integral part of the not very strong aesthetic integrity of the work. Formalism vs. Exuberance There are two poles in the reception of Dickens: The formalist pole which sees Dickens’ novels as violations of the novel genre. The formalist pole, which may be personified in Henry James, focuses on Dickens’ additive plots, his digressions and his perpetual introduction of new characters. These are then either criticized, or adherents to Henry James’ views of the novel or New Critics seek to show that there is after all structural unity in Dickens’ works. The exuberance pole sees one salient point about Dickens’ whole production, i.e. the sheer excessiveness and scope of his fictional world. The reader is time after time overwhelmed by the magnitude of the settings, the number of characters, the emotional overload, and the extravagance and excess of language. Until around 1850 most critics belonged to the exuberance pole, but after this time a problem is seen in the absence of form in Dickens’s novel. The notion of absence of form was extended to a lack of morals and ideology. From this time onward the question is how the exuberance in Dickens' writings can be reconciled with the constraints imposed on his imagination by the form of the novel. It was typical of late Victorian critics such as Ruskin, Arnold and Carlyle that they saw Dickens’ writings in a biological light as organic life. Biological or natural life grew abundantly, but in a structured and ordered manner. Dickens’ writings grew almost biologically, but his lack of natural structure was lamented. The key to a historical understanding of the form of Dickens’ novels can be found in the content: man as an urban creature. In 1858 Walter Bagehot contextualised this position. Dickens was a writer who depicted urban or metropolitan life, which per definition was unnatural, so the form or rather formlessness in Dickens is the formlessness of metropolitan life with its fragmented amount of sense impression: ‘Everything is there, and everything is disconnected… each scene, to his mind, is a separate scene, - each street a separate street.’ (Quoted by Steven Connor in Charles Dickens, Longman, Harlow 1996, pp. 2-3). The urban mode of perception can be witnessed in Sketches by Boz (‘Thoughts about People’), which is not a novel; but significantly the same kind of perception is also noticeable in the novels. Something in a person in the cityscape catches Dickens' attention, usually it is an external characteristic, and this characteristic is then focused on to such an extent that it becomes the whole character. Metonymically Dickens identifies a whole character with an isolated characteristic of it. Bagehot calls this form of productive perception vivification. In The Pickwick Papers ch. 27, ‘Samuel Weller makes a Pilgrimage to Dorking, and beholds his Mother-in-law’ vivification is at work in the case of the red-nosed man “who caught Sam’s most particular and especial attention at once”. It is the red nose as the attribute of the alcoholic which forms the subsequent development and fictional creation of this character. It is an external characteristic which creates a character and a sub-plot. Much later than Dickens in an article “Die Grossstädte und das Geistesleben” (“The cities and spiritual life”) from 1903 the German sociologist Georg Simmel (1858-1918) has described how the overflow of sense stimuli in the big cities forces the individual into an attitude of detachment, which prevents him or her from anything deeper than a superficial and 2 surface-like relationship with all the strangers met in the street. Also Walter Benjamin (18921940) has in 1933 described urban perception in “Über einige Motive bei Baudelaire” (On Some Motifs in Baudelaire). Again this is later than Dickens. Benjamin distinguishes between two forms of perception. Rural perception gave rise to experience (German: Erfahrung), whereas urban perception with its constant and massive bombardment forced the individual into a defensive posture which prevented anything but surprise or chock experience (German: Erlebnis). The urban experience is tied to the moment, and is not preserved as anything learnt. The turmoil of sense impressions in the metropolis and its influence of the formal qualities of the work is not only mirrored in the novels of Dickens, but the new film medium with its montage technique and rapid editing testified to the sense qualities of urban existence. One example is Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin, die Symphonie einer Grossstadt from 1927. Henry James has critizised Dickens' mode of writing as being ‘manufacture of fiction’, and it is true that Dickens form of production was almost industrial: The endless assembly line production of instalments, sometimes for several novels at a time with deadlines to be met and the printer’s boy waiting at the door. However, again this tendency in Dickens can be explained if it is contextualised historically . The exuberance in Dickens and in his texts is the exuberance and energy of the expanding and growing industrial capitalism of the time. Postmodernism and Dickens Present-day reception of Dickens can be seen in a postmodern light. Like many postmodern texts Dickens cannot be placed in the taste hierarchy, but he is a mass author. The postmodern concept of hybridity can be found in the almost arbitrary shape any Dickens text may assume. When reading or watching Dickens a present-day audience may experience the feeling of deja-vu. This aspect is not unlike the effect of postmodern intertextuality. Finally, the postmodern genre historiographic metafiction with its convergence of history-writing and story-writing has its parallel in our historical conception of the Victorian period based on Dickens’ fiction. Dickens, Narration and Ideology How could Dickens be popular with all social classes in Victorian England from top to bottom? His social criticism does not appear to have estranged the middle classes or the upper classes, and his lack of a clear radical message does not appear to have estranged the lower classes. On the contrary, everybody has sought to claim that Dickens is a champion of their cause, and as George Orwell writes in his essay on Charles Dickens, Dickens’ texts are so easy to recruit for a political cause. When one has to define precisely what Dickens’ ideology is, he suddenly seems to be a wet, and slippery piece of soap, yet a feeling remains that Dickens somehow is more critical of Victorian bourgeois society than he is for it. How then does Dickens manage to convey critical attitudes in his novels? In Oliver Twist he attacks the workhouse system, in The Pickwick Papers the retired businessman Mr. Pickwick does experience some dark aspects of life in the country and in London and he cannot remain innocent, in Hard Times the whole materialist ethos of the Victorian period is violently attacked. Finally, in Little Dorrit the prison becomes an all-encompassing metaphor for society. 3 In the following four introductions the answers to the questions asked here will relate to the discussion presented above whether Dickens’ novels are exuberant works without form or whether they do possess formal qualities. The answers will suggest that in all the four novels there are highly complicated narrative structures that have as their aim in different ways to disguise and conceal a rather radical ideology, an ideology that would have been unacceptable to Dickens’ broad audience if it had not been enveloped in these narrative structures. 4