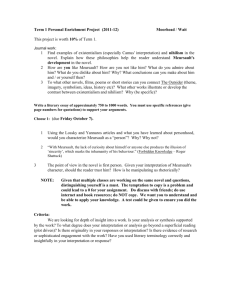

Conference Schedule - University of Chicago Law School

advertisement

CRIME IN LAW AND LITERATURE THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO FEBRUARY 7–8, 2014 Organized by Alison L. LaCroix, Richard H. McAdams, and Martha C. Nussbaum FRIDAY FEBRUARY 7 10:00 a.m.–12:00 p.m. Session 1: Student Papers Emily Buss (University of Chicago Law School), Chair. Daniel Telech (University of Chicago, Department of Philosophy, PhD Program), Mercy at the Areopagus: A Nietzschean Account of Justice and Joy in the Eumenides The Oresteia trilogy ends joyfully: Orestes is acquitted of the crime of matricide; the Furies become honorable; and both of these because Athens initiates the rule of law. In this paper, I defend a Nietzschean reading of justice and joy in the Eumenides. I argue that the transition from the Atridae cycle of vengeance to rule of law is neither the work of cool rationality nor lacking in substantial arbitrariness. Rather, it is largely due to Athena’s conciliatory function that the Furies undergo the transformation from an orientation of resentment to an orientation of mercy. This change marks what Nietzsche calls the “self-overcoming of justice.” In addition to providing the Furies with their long-desired recognition from the Olympian gods, this advance in justice promises to improve the well-being of Athens’s citizens. I maintain that the Eumenides is optimistic and progressive in one important sense—namely, relative to human aspirations and needs—without thereby serving as an example of Socratic Optimism. Dhananjay Jagannathan (University of Chicago, Department of Philosophy, PhD Program), Tragedies of Youth: Responsibility in Euripides’ Bacchae and the Law Bernard Williams argues in Shame and Necessity that there are many conceptions of responsibility built up out of the same basic elements—cause, intention, state, and response—and that we can only appreciate the notions of agency and responsibility at work in Greek tragedy if we distinguish these elements and take note of the differences and lack of priority between a modern idea of ‘moral’ responsibility and the Greek idea or ideas. In this paper, I develop Williams’s suggestion, made in passing, that there are many modern notions of responsibility, too, including the notion of strict liability in the law. I argue, contra Williams, that all notions of responsibility are moral in the sense that they attribute something to the agent, and that the application of strict liability whether in tort or criminal law shows that what Williams calls ‘moral responsibility’ is a subtle and graded phenomenon. That is why we can account for cases of tragic action in modern terms without appealing to the Greek cultural context, including cases where legal recourse is appropriate. All the same, I believe we can come to better understand what we think about tragic cases by exploring richly described literary cases. Accordingly, I consider Euripides’ Bacchae and the fate of the young Pentheus in terms of the diminished moral responsibility we now attribute to juvenile criminal offenders. From this comparison, I aim to show that we can better understand why it is that a youthful character diminishes responsibility itself and not simply culpability or the severity of an appropriate sentence when calibrated to the prospects for rehabilitation or reform. In this way, we see that juvenile crime, even in the most heinous cases, carries with it an element of the tragic, an insight often ignored in the treatment of young offenders in American courts. Marco Segatti (University of Chicago Law School, JSD Program), Law’s Promise: Crime, Religion, and Revolt in Manzoni’s Promessi Sposi Manzoni’s Promessi Sposi is a classic of Italian literature. I will try to comment closely on the complex interplay between religion, law and civil disobedience that is depicted by Manzoni in three episodes narrated in the novel. All these episodes, I shall argue, provide a powerful, and yet very controversial, account of law’s promises and failures, within oppressive societies, in protecting people’s livelihood from crimes ordained by the powerful and in preventing social disasters, like the great famine and the ensuing plague in Milan. Within this broad framework, central attention will be paid to Manzoni’s own account of the role of religion—as a last resort for the weak and helpless, merely providing consolatory relief in a world filled with injustices; or as a driving force of history (the Divina Provvidenza), leading the “good” to prosper and the “bad” to punishment in the final “happy ending”; or, as a practice arising in response to the recognition of human vulnerabilities and that (as one human practice among others) may help people to unveil the humanity in themselves and in others. Finally, I will try to show that, notwithstanding the fact that the most accurate reading of the novel would place Manzoni’s explicit working theory of law and religion much closer to the first two interpretations, it is actually possible, by critically reading the novel to find the third one. In turn, I will argue that this slightly “countertextual” interpretation of the novel’s own ethical and political potentialities can motivate an entirely secular interest in both literature and religion, as possible human responses to crime and injustice, since they both begin by providing “rich descriptions” of (and arise out as responses to) human striving and vulnerabilities. Stephen Richer (University of Chicago Law School, JD Program), The Not-So-Magical Effects of Expansive Prosecutorial Power: Harry Potter and Criminal Law In the Harry Potter books, author J. K. Rowling asks the same question that all wartime governments must ask: “Should we sacrifice personal liberties to better equip ourselves to fight our enemy?” The Ministry of Magic in Rowling’s world chooses “yes.” In The Chamber of Secrets, the criminal process is suspended because of the Ministry’s desperate need to show action (the imprisonment of Rubeus Hagrid without trial). A similar storyline is repeated in books six and seven with the imprisonment of innocent characters such as Stan Shunpike such that, once again, the Ministry may be seen as active and might, by fortune, capture a true criminal by imprisoning many. Even the protagonist of the books—Harry Potter himself—is subjected to a faux criminal trial that is stripped of the normal procedures of the Wizarding world. Rowling clearly disagrees with the Ministry’s decisions. Ministry workers are portrayed as buffoons or, at best, destructively overzealous. Rowling delivers the ultimate rebuttal to the Ministry’s actions when, in book seven, the Ministry is overtaken by evil forces who use the expanded government powers against the book’s heroes. Clearly Rowling sees government power as a double-edged sword, used for good or evil. This paper brings to light the Ministry’s disregard and suspension for normal criminal processes throughout the Harry Potter books. Then, Rowling's opinion of these actions is revealed based on the later fate of the characters. The paper asks if Rowling's worldview is accurate: Is a fair criminal process at odds with waging a successful war? The answer to this question is important because Harry Potter is the first book that many young Americans come to adore, reread, and interpret as they come of age in a world that is increasingly asking exactly this same question. 1:30 p.m.–3:45 p.m. Session 2: Criminal Histories Will Baude (University of Chicago Law School), Chair. Alison LaCroix (University of Chicago Law School), A Man for All Treasons: Crimes by and Against the Tudor State in the Novels of Hilary Mantel This paper discusses the crime of treason as depicted in Hilary Mantel’s novels Wolf Hall (2009) and Bring Up the Bodies (2012). In the novels, Mantel provides a corrective to the enduring view of Thomas Cromwell as at best a Tudor-era fixer, and at worst as a murderer and torturer—a view made famous by Robert Bolt’s play A Man for All Seasons (1960). Instead, Mantel’s Cromwell is the industrious creator of the modern administrative state. In this characterization, Mantel follows in the scholarly path of Geoffrey Elton, whose Tudor Revolution in Government (1953) rehabilitated Cromwell by arguing that he reformed English government by replacing personal rule with modern bureaucracy and systematizing the royal finances. In different ways, both Mantel’s and Elton’s account rebut the image of Cromwell as a criminal. But I argue that Mantel’s Cromwell in fact should be seen as representing two species of crime: crimes against the state, in the form of treason; and crimes by the state, in the form of espionage and torture. The novels present both forms of crime as occurring at the same historical moment in which the modern state was being formed. Because crimes against the state and by the state both presuppose the existence of the state itself, Mantel’s and Elton’s modernizing Cromwell may not be as distinct from Bolt’s devious Cromwell as the competing accounts would suggest. Marina Leslie (Northeastern University, English Department), Labors Lost: Infanticide, Service, and the Unlikely Resurrection of Anne Green In late November 1650, Anne Green, a 22 year-old Oxfordshire servant, was taken into custody for the murder of her newborn child. When to everyone’s surprise she revived on the anatomists’ table at Oxford University, she presented a unique legal, political, and rhetorical problem for the Oxford experimentalists who revived her. Was she guilty or innocent? Subject to the law or saved by God? This paper explores how these questions were managed in a number of poems in English, French, and Latin by renowned Oxford scholars in 1651 and concludes with Green’s more recent literary legacy in novels by Ian Pears and others. Richard Strier (University of Chicago, Department of English) & Richard McAdams (University of Chicago Law School), Cold-Blooded and High Minded Murder We explore in detail the crime Othello commits when he kills Desdemona, a matter made complex and contradictory by the details of the scene and by the state of mind in which Othello is presented (and presents himself) as being in before the act. After previously raging with jealousy, Othello is eerily composed when he enters the bedchamber; he imagines himself as determinedly, religiously, even lovingly carrying out justice against a women he loves and he scrupulously refuses to shed her blood or mar her physical perfection. Pointing in one direction, the justice theme seems to invoke the legal distinction from Bracton that killing “done out of malice or from pleasure in the shedding of human blood” is murder while killing “done from a love of justice” is not. Yet Othello’s deliberateness also points in the opposite direction, as a hot blooded killing, done on a sudden affray, was manslaughter rather than murder, suggesting that Othello would have been guilty of the lesser crime had he torn “her all to pieces” when first convinced of Desdemona’s adultery, but is ultimately guilty of murder because his rage had dissipated. However, and finally, the crime might have been seen—as Othello sees it—as an honor killing, which the juries of the period would have been inclined to treat with leniency, despite the absence of hot blood. Early modern England may not have been an “honor culture” in quite the way that early modern Spain was, but it was not a culture to which this context was at all unintelligible or clearly “foreign.” Barry Wimpfheimer (Northwestern University, Department of Religious Studies), “Were All of Israel Established as Liars?”: Perjury and Ancient Jewish Narratives The Babylonian Talmud at Makkot 5b records a debate surrounding a hypothetical in which a woman who has already produced two sets of perjuring witnesses attempts to produce a third set of witnesses. The debate pits two third century rabbis against each other: one believes that the litigant loses the ability to produce a third set of witnesses while the other contends that witness credibility is unrelated to the litigant and must be evaluated based on the default presumption of witness credibility. In this paper, I will connect this legal discussion of perjury to ancient Jewish folk beliefs about women who are twice widowed and are referred to in post-Talmudic literature as “Qatlaniyot”— “Killer Wives.” The road to this connection will travel through the biblical story of Judah and Tamar as well as other rabbinic stories about perjury and the “killer wife.” Along the way I will show that both the perjury story and stories about the “killer wife” reflect the absorption of the myth of Pandora’s box into Rabbinic culture and complicate our understanding of the relationship between Rabbinic views of women and the views of their broader culture. The paper will reflect upon the relationship between law and superstition and consider the overlap between legal constructs and those that emerge in folk religion. In the case of the rabbis, I will show that the example of the “killer wife” reflects a pattern of rabbinic thought in which the rabbis consistently characterize superstition itself as female-gendered. 4:00 p.m. Musical Interlude: Jajah Wu, Gary DeTurck, and Martha Nussbaum Performance of Extracts from Aeschylus’ Oresteia, Starring Richard Posner and Other Faculty and Student Actors 5:15 p.m.–6:15 p.m. Plenary Talk and Panel Scott Turow, Plenary Speaker Panel: Alison LaCroix, Judge Diane Wood, Scott Turow, and Richard McAdams SATURDAY FEBRUARY 8 9:45 a.m.–12:00 p.m. Session 3: Race and Crime Randy Berlin (University of Chicago Law School), Chair Justin Driver (University of Texas School of Law), Bigger Thomas and Smaller Thomas In Justice Clarence Thomas’s account of his life before joining the Supreme Court, he includes several striking references to Bigger Thomas, the protagonist of Richard Wright’s Native Son. This paper will examine Justice Thomas’s reading of Bigger Thomas, and analyze how his invocations of Wright’s fictional character sit alongside some of his more notable opinions in the criminal law realm. Martha Nussbaum (University of Chicago, Law School and Department of Philosophy), Reconciliation without Law: Paton’s Cry the Beloved Country Here’s a common view: The pursuit of justice in a situation of great injustice, requires anger. People mobilize through their anger against injustice, and their anger is both a motivation and a creative force in the pursuit of justice. Correspondingly, it is also often thought that political reconciliation requires a process of public atonement on the part of the formerly unjust: they acknowledge their wrongs, and if they ask humbly enough they may receive forgiveness. Forgiveness is here understood as a suspension of angry attitudes. Desmond Tutu, for example, uses Christian ideas of atonement and contrition to argue that there is “no future without forgiveness.” But these claims may be doubted. Some great leaders, for example Mohandas Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr., have been very suspicious of anger, feeling that it deforms the personality and impedes a future-directed search for reconciliation. But if there is no anger, there is also no forgiveness, not of the classic anger-waiving sort. What might the alternative be? Alan Paton’s apartheid-era novel Cry the Beloved proposes a personal analogue of a public process in which a nation riven by injustice might possibly engage. Paton, whose other career was that of superintendent of a progressive youth correctional institution, was deeply immersed in the struggle against apartheid throughout his life, and his novel is one of the movement's most eloquent statements. The protagonists are two fathers: a black man whose son has murdered a white man, and a white man whose son is the murder victim. The scenario is a natural one for the classic drama of contrition, apology, and forgiveness. But this is not what happens. As the two fathers turn aside from anger to imagine, with generosity, a future of interracial cooperation and constructive work, they create, outside the corrupt legal order, a vision of a new legal order, one committed to justice, but generous and forward-looking in spirit. It is precisely this spirit of non-angry and generous reconciliation that was eventually instantiated by Nelson Mandela. The novel, which ends on a note of prophetic hope, has had the good fortune to have its vision realized, albeit by flawed human beings, and thus incompletely. Kenneth Warren (University of Chicago, Department of English), On Sanctuary and Borders: William Gardner Smith’s The Stone Face and Michael Haneke’s Caché This paper will consider the problem of representing and acknowledging state-sponsored crime against noncitizens, using William Gardner Smith’s 1963 novel The Stone Face and Michael Haneke’s 2005 film Caché as points of departure. Smith’s novel, which follows the political awakening of an African American expatriate in Paris, and Haneke’s film, a tale of surveillance that uncovers a repressed memory of injustice, are two of the few imaginative works to take up the massacre of more than 200 Algerian protestors by the French police on October 17, 1961. 1:00 p.m.–3:30 p.m. Session 4: Responsibility and Violence David Weisbach (University of Chicago Law School), Chair Saul Levmore (University of Chicago Law School), Kidnap, Credibility, and The Collector Kidnap, and especially ransom kidnapping, has a long history, but it has not attracted quite as much literary attention as murder and rape. It raises interesting questions about whether criminal law properly accounts for precaution costs, or fright-induced changes in behavior, as are especially likely to follow in the wake of highly publicized kidnappings. The crime itself is difficult to carry out because ransoms are difficult to collect and because threats, which are at the core of kidnaps, suffer from various credibility problems. The cornerstone of the present essay is John Fowles’ chilling novel, The Collector, about an abductor who seeks not ransom but rather benefits that we associate with consensual relationships. The novel focuses attention on the ways in which people control or even possess one another and, therefore, on the question of how and why we criminalize some controlling behaviors but not others. Along the way and in uncanny fashion, The Collector suggests many interesting features of threats and of kidnapping in particular. Jonathan Masur (University of Chicago Law School), Premeditation and Responsibility in The Stranger In The Stranger (L’Etranger), Albert Camus uses the prosecution, trial, and eventual execution of his protagonist, Meursault, as a demonstration of the injustice of French society. The French are portrayed as incapable of accommodating an outsider (Meursault) who eschews the range of human emotions and motivations they have come to expect. Many critics have focused upon Meursault’s conviction for premeditated murder—actually, assassination—as the touchstone for this injustice. Most famously, Meursault is apparently undone by his failure to shed tears at his mother’s funeral some months earlier. But Meursault’s conviction, and the disquiet Camus means for it to provoke, can only be understood in relation to what might have occurred at a “fairer” trial. Camus introduces that information through Meursault’s lawyer, who suggests at various moments that Meursault’s act of homicide might have been justified—which would result in Meursault being acquitted—or that he might face only a short prison sentence for a lesser crime. Yet a close reading of the French Penal Code reveals no such possibility. Even had his trial been conducted fairly, it is implausible that Meursault could have escaped serious punishment for his crime. Whatever sympathy the reader might attach to Meursault is nurtured by Camus’ mischaracterization of French law. A fuller understanding of Meursault’s responsibility for the killing, his mens rea, and the range of likely carceral outcomes leads to a very different set of conclusions regarding Meursault’s actions and those of his inquisitors. Mark Payne (University of Chicago, Department of Classics), Before the Law: Imagining Crimes against Trees My paper begins with a passage from Jakob Grimm’s Deutsche Rechtsalterthümer that records talionic punishments for taking the life of a forest tree. In an effort to understand how talionic punishment could have seemed appropriate in such a case, I examine a number of fictional examples from antiquity that describe violence against trees in an era before the institution of law as such. In these passages, trees are presented as beings that live though self-care alone. As such, they provoke violence on the part of human beings who suspect that their own dependence on others is akin to the domestication of animals. Talionic punishment for harming a forest tree is thus grounded in the fantasy that the wildness of forest trees stands for the wildness of their human guardians. In conclusion, I discuss a passage from Nathaniel Hawthorne’s American Notebooks in which the notion of sacrilege is invoked in relation to harming orchard trees, but which grounds this possibility in a different relationship between the lives of trees and human beings as companion species to one another. Blakey Vermeule (Stanford University, Department of English), Protagonists, Antagonists, Egalitarianism, Outrage It is a striking and perhaps unappreciated fact of modern literature that much very direct moral talk—talk about moral dilemmas, talk about how to behave in ethically challenging situations, talk about serious ethical compromises and lapses—gets presented to us through gangster fiction—not just crime fiction, but fiction about organized crime. My talk explores this dramatic staging of ethical set-pieces and presents a hypothesis about why that should be the case. My main example will be the first great piece of gangster fiction, Milton’s Paradise Lost. The talk considers such topics as when and under what conditions we root for evil, the so-called puzzle of imaginative resistance, how moral dilemmas are framed with reference to groups, and why a background of tribal loyalty and the threat of defection is an especially fruitful stage for the sorts of scenarios that especially prime our ethical intuitions. 3:45 p.m.–6:00 p.m. Session 5: Suspicion and Investigation Jennifer Nou (University of Chicago Law School), Chair Bernard Harcourt (University of Chicago Law School), George Orwell’s 1984: Thought-crimes in the Age of the NSA George Orwell’s novel 1984 is a story of thought-crimes (and actual crimes) against a Big Brother state. Sales of Orwell’s 1984 soared on Amazon.com after the disclosures by Edward Snowden that the United States government, through its National Security Agency, had access to practically everything that users do on the internet. According to Bloomberg news, the book “moved to the No. 3 spot on Amazon’s Movers & Shakers list over a 24-hour period.” Various editorial headlines referred to Orwell’s novel, noting that “NSA surveillance goes beyond Orwell’s imagination,” “Orwell’s fears refracted through the NSA's Prism,” or “NSA PRISM: 3 Ways Orwell’s ‘1984’ Saw This Coming.” This paper will revisit Orwell’s novel and its focus on thought-criminality in the wake of the recent intelligence disclosures. Caleb Smith (Yale University, English Department), Crime Scenes: Fictions of Security and Jurisdiction The main line of Law and Literature criticism has concerned itself with narrative; our work has explored how stories are told in legal and literary worlds, with their differing genres, codes, and norms. My paper argues for an alternative approach, one that emphasizes setting (broadly conceived) over plot, spatial claims to jurisprudential standing over allegories of transcendent justice. My case study is the popular literature that emerged from the struggle over Cherokee “removal” between the 1830s and the 1850s: the minister Samuel Worcester’s letters from a Georgia prison; the lawyernovelist William Gilmore Simms’s “border romances”; and the Cherokee writer John Rollin Ridge’s Joaquín Murieta, sometimes known as the “first Native American novel.” Most recent scholarship approaches this archive through political concepts such as ideology and (especially) sovereignty. From Worcester’s landmark case forward, however, the legal question of jurisprudence was at the heart of the crisis. Simms’s crime fiction suggested that encounters between antagonistic communities, along the edges of jurisdictions, would produce crime; he argued for the imposition of a single authority to secure the peace. Ridge reworked the same sensational genre to produce the figure of the outlaw as an agent of vengeance in newly annexed California, with its syncretic legal system and its rampant, racist vigilantism. I show how each of these texts attempted, in its way, to coordinate the relations between territories and moral communities in an imperial context. Steven Wilf (University of Connecticut School of Law), The Legal Historian as Detective In 1910, Roscoe Pound famously published his distinction between law in the books and law in action. Yet not all action takes place off the printed page. By focusing upon detective novels, it is possible to see what often eludes criminal trials—the labyrinth of criminal psychology, a fullydeveloped social context, and the lasting effects of the criminal act as social rupture. Detective novels, mysteries, and police procedurals create a parallel, more deeply described world than the traditional sphere of legal cases. Situating, of course, is the particular domain of legal historians. What might the gaze of the legal historian bring to understanding criminality? This essay will interrogate the particular observing eye found in detectives who are also historians. It examines two (legal) historian detectives—those of Israeli author Batya Gur and British novelist Sarah Caudwell. Batya Gur’s protagonist, Michael Ohayon, a Sephardic Jew who was trained in history at the largely Western European Hebrew University in Jerusalem, operates as an outsider-observer. The Ohayon novels revolve around the determination of the social norms of a particular segment of society—and the knowledge that the violation of deeply held norms might lead to murder. Caudwell’s quintessential Oxford Don Hilary Tamar is a legal historian whose (and this provides the outsider touch) gender is never specified. Fussy, pedantic, and acutely aware of the interpretive intricacy of medieval English legal documents, Tamar serves as a guide through the uncertain landscape of clues. If Ohayon reads social norms, Tamar’s great gift is familiarity with the hermeneutics of legal texts. Legal historians, after all, always find themselves caught between the Scylla and Charybdis of text and context.