Attention, Shoppers: Kmart to Buy Sears for $11

advertisement

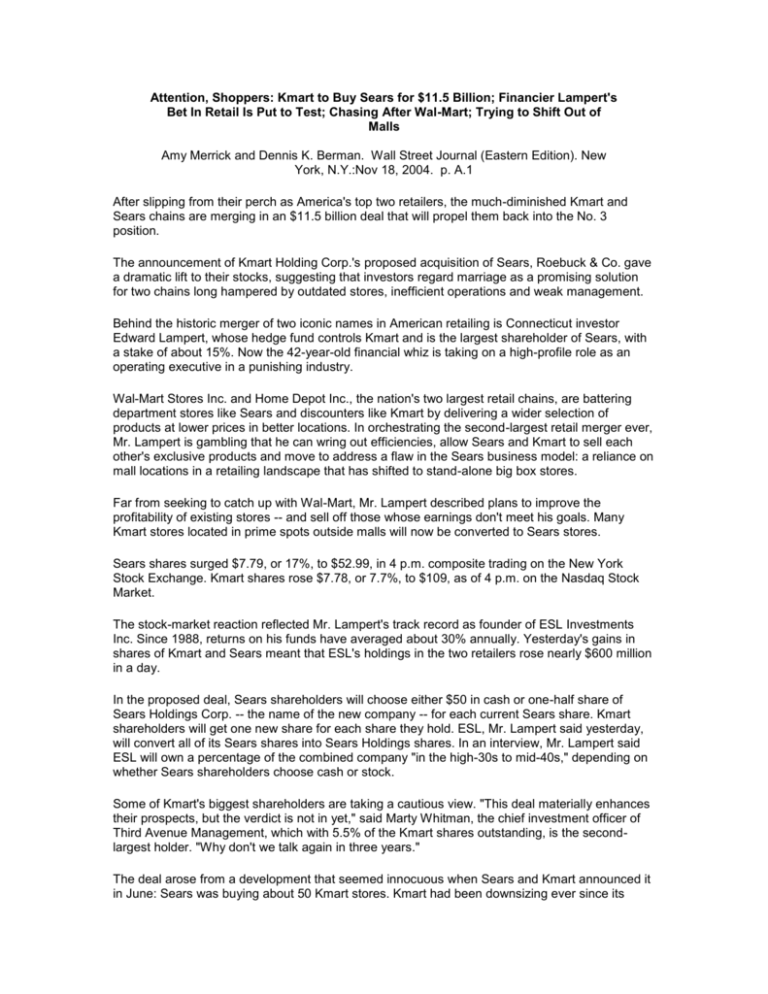

Attention, Shoppers: Kmart to Buy Sears for $11.5 Billion; Financier Lampert's Bet In Retail Is Put to Test; Chasing After Wal-Mart; Trying to Shift Out of Malls Amy Merrick and Dennis K. Berman. Wall Street Journal (Eastern Edition). New York, N.Y.:Nov 18, 2004. p. A.1 After slipping from their perch as America's top two retailers, the much-diminished Kmart and Sears chains are merging in an $11.5 billion deal that will propel them back into the No. 3 position. The announcement of Kmart Holding Corp.'s proposed acquisition of Sears, Roebuck & Co. gave a dramatic lift to their stocks, suggesting that investors regard marriage as a promising solution for two chains long hampered by outdated stores, inefficient operations and weak management. Behind the historic merger of two iconic names in American retailing is Connecticut investor Edward Lampert, whose hedge fund controls Kmart and is the largest shareholder of Sears, with a stake of about 15%. Now the 42-year-old financial whiz is taking on a high-profile role as an operating executive in a punishing industry. Wal-Mart Stores Inc. and Home Depot Inc., the nation's two largest retail chains, are battering department stores like Sears and discounters like Kmart by delivering a wider selection of products at lower prices in better locations. In orchestrating the second-largest retail merger ever, Mr. Lampert is gambling that he can wring out efficiencies, allow Sears and Kmart to sell each other's exclusive products and move to address a flaw in the Sears business model: a reliance on mall locations in a retailing landscape that has shifted to stand-alone big box stores. Far from seeking to catch up with Wal-Mart, Mr. Lampert described plans to improve the profitability of existing stores -- and sell off those whose earnings don't meet his goals. Many Kmart stores located in prime spots outside malls will now be converted to Sears stores. Sears shares surged $7.79, or 17%, to $52.99, in 4 p.m. composite trading on the New York Stock Exchange. Kmart shares rose $7.78, or 7.7%, to $109, as of 4 p.m. on the Nasdaq Stock Market. The stock-market reaction reflected Mr. Lampert's track record as founder of ESL Investments Inc. Since 1988, returns on his funds have averaged about 30% annually. Yesterday's gains in shares of Kmart and Sears meant that ESL's holdings in the two retailers rose nearly $600 million in a day. In the proposed deal, Sears shareholders will choose either $50 in cash or one-half share of Sears Holdings Corp. -- the name of the new company -- for each current Sears share. Kmart shareholders will get one new share for each share they hold. ESL, Mr. Lampert said yesterday, will convert all of its Sears shares into Sears Holdings shares. In an interview, Mr. Lampert said ESL will own a percentage of the combined company "in the high-30s to mid-40s," depending on whether Sears shareholders choose cash or stock. Some of Kmart's biggest shareholders are taking a cautious view. "This deal materially enhances their prospects, but the verdict is not in yet," said Marty Whitman, the chief investment officer of Third Avenue Management, which with 5.5% of the Kmart shares outstanding, is the secondlargest holder. "Why don't we talk again in three years." The deal arose from a development that seemed innocuous when Sears and Kmart announced it in June: Sears was buying about 50 Kmart stores. Kmart had been downsizing ever since its early 2002 descent into bankruptcy court, from which it had emerged in May of 2003 with fewer debts and with a new majority owner: Mr. Lampert. He had been scooping up the retailer's debt, and invested more during bankruptcy proceedings until he had gained control. After the sale of stores, Mr. Lampert and Sears Chief Executive Alan Lacy talked throughout the summer about a larger deal. Originally talk centered on a Sears acquisition of Kmart. But then Kmart stock soared, largely because Mr. Lampert had boosted profits by cutting back on inventory, slashing costs and stopping rampant discounting. The higher stock price forced Sears into the target role. Early this month, another hitch developed: Vornado Realty Trust, a New York real-estate fund, disclosed that it had amassed a 4.3% Sears stake. Observers speculated that Vornado saw value in Sears real estate that wasn't reflected in the stock price. The Vornado news boosted Sears stock, raising the possibility that Sears would become too expensive to acquire. Messrs. Lampert and Lacy pushed hard to quickly strike an agreement. One board member said the prospects of a deal weren't even discussed at an October board meeting. "We still didn't have a final deal on price until Tuesday at midday," says one person familiar with the matter. "We were concerned the Sears price might get away from us." Both Mr. Lampert and Mr. Lacy saw a merger as a possible solution to the Sears chain's old affinity for traditional malls. Sears stores followed the population growth into the suburbs over the decades, but by the late 1990s malls had lost much of their retailing prowess. More than 80% of consumer shopping dollars, excluding purchases of food and drugs, are now spent in locations outside malls, according to research by Customer Growth Partners LLC, a consulting company in New Canaan, Conn. That compares with about 60% in 1995. And six of the nation's largest retailers aren't part of malls -- double the number in the late 1990s. "The problem is they are not where the customers are, and that's the big opportunity," said Mr. Lampert of Sears yesterday. "It is not that the retailer per se is weak, but if you have the greatest store and it's not where the customers are, that's a problem." The son of a lawyer and a homemaker in the New York suburb of Roslyn, N.Y., Mr. Lampert started focusing on his financial future after his father died of a heart attack when Mr. Lampert was 14. He aggressively courted well-connected classmates and professors as an undergraduate student at Yale University. Mr. Lampert joined Goldman Sachs after college, finding a mentor in Robert Rubin, who was at the time head of risk arbitrage at the firm and eventually U.S. Treasury secretary. Mr. Lampert left to start ESL in 1988, at the age of 25, with just about $25 million to invest. Mr. Lampert's investors amount to a who's who of the wealthy and smart set, including representatives of the Ziff and Tisch families, as well as David Geffen and Michael Dell. ESL also owns large stakes in AutoZone Inc., an auto-parts retailer, and car dealer AutoNation Inc. Last year, Mr. Lampert's desire for secrecy was reinforced, say people close to him, when he was kidnapped from the garage of his office building in Greenwich, Conn. He eventually persuaded the kidnappers to let him go in exchange for $40,000, according to published reports. During the four-year reign of Mr. Lacy, a former chief financial officer, Sears has cut costs but failed to update its image as yesteryear's retailer. Even after it bought the relatively high-end Land's End brand, sales continued to sputter. Mr. Lacy, 51, will be chief executive of Sears Holdings. Under him, as chief executive of Kmart and Sears Retail, will be Aylwin B. Lewis, 48, who joined Kmart one month ago as CEO. Before that he was a top executive of YUM Brands Inc., owner of the KFC and Taco Bell chains. Speculation has been rampant that Sears might recruit Vanessa Castagna, the number two executive at J.C. Penney Co. who recently resigned after failing to get the top job. In an interview, Ms. Castagna said she has been flooded with offers, and that she has been contacted by Sears but is not currently involved in any negotiations. She said she would not be making any decisions until after Jan. 1. Ms. Castagna said she was surprised by the merger. "I think this will make Sears more competitive with Lowe's and Home Depot," she said. But "I think it is going to take a lot of capital to execute their vision." Lehman Bros. was Kmart's financial adviser and Simpson Thacher & Bartlett LLP its legal counsel. Morgan Stanley was Sears's financial adviser and Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz its legal counsel. Calling Sears the stronger brand, Mr. Lampert yesterday spoke about the chance to expand that chain's products and presence into Kmart country. Mr. Lacy said that "several hundred" Kmart stores could be converted to Sears stores. Some would be part of a new chain called Sears Grand, which adds products such as food and CDs to the typical Sears store. Both stores have popular exclusive brands that could cross from one store to the other. Investors clearly expect Martha Stewart Everyday products -- a big seller for Kmart -- to gain access to Sears stores, because shares of Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia Inc. rose yesterday on news of the acquisition. Martha Stewart products already sell in Sears stores in Canada. Among the brands for which Sears long has been famous, Craftsman tools will likely be introduced to the shelves of Kmart, perhaps bolstering its ability to compete against Home Depot. A bigger question is whether Sears will move its home-appliance products into Kmart stores. Through its Kenmore brand as well as through the sale of Whirlpool, General Electric and Maytag models, Sears is the nation's largest purveyor of refrigerators, washers and dryers, although it has been losing market share in recent years to Home Depot and Lowe's Cos. The two retailers in yesterday's deal went wrong in different ways. Beginning with its first large mail-order catalog in 1896, Sears pioneered retailing in the U.S., dotting the land with department stores from coast to coast. In the 1980s, it expanded into a brokerage business and real estate, but it later decided those businesses were distractions and disposed of them. The rise of discounters and popularity of high fashion squeezed middle-brow department stores such as Sears. Customers wanting low price started going to Wal-Mart and Target Corp. Customers wanting quality would step up to Nordstrom or specialty retailers such as Gap. Meanwhile, so-called category killers such as Home Depot came along and weakened Sears. During Mr. Lacy's four-year tenure, Sears has repeatedly overhauled its stores and cut costs in an effort to compete with a host of fast- growing rivals, from Wal-Mart and Target to Home Depot and Lowe's. In 2002, Sears purchased the Lands' End apparel brand for $1.86 billion. In July of 2003, it sold its credit-card business for about $3 billion to Citigroup Inc. While better known for its department stores and selling Craftsman tools and Kenmore appliances, credit cards had been a big part of the company for 91 years. Kmart is a tale of bad management, going back decades. Kmart, with roots that stretch back to 1899 under the Kresge chain, opened its first Kmart store in 1962. It quickly flooded the country with discount stores. In the late 1970s, Wal-Mart's sales were 5% of Kmart's; it had 150 stores to Kmart's 1,000 or so, mostly in urban locations. Wal-Mart, meanwhile, invaded rural America, where it quietly perfected a format of using technology to reduce inventory, keep shelves stocked and offer the lowest prices. By the time it began meeting Kmart head on, Wal-Mart enjoyed a significant price advantage that a series of Kmart executives failed to overcome. Following a disastrous management scheme to load up on inventory and slash prices to compete with Wal-Mart head-on, Kmart filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy-court protection in January 2002. Mr. Lampert then made his move. Through ESL, he acquired enough debt to emerge from the company's reorganization with about half of Kmart shares. The company emerged from court protection in May 2003, with Mr. Lampert as its chairman. The combined company will be based in Hoffman Estates, Ill., where Sears has its headquarters. Kmart will continue to have offices in Troy, Mich. Of the combined company's 10 directors, seven will come from Kmart's board, the other three from the Sears board. The deal is likely to be investigated by the Federal Trade Commission, which reviews most retail mergers, but seems unlikely to face significant antitrust opposition given the changing marketplace and the power of industry leader Wal-Mart. Taking Inventory Kmart: Founded: 1899, as S.S. Kresge Co., by Sebastian S. Kresge Headquarters: Troy, Mich. Chairman: Edward S. Lampert CEO: Aylwin B. Lewis Employees: 144,000 Stores: 1,500 Key brands: Martha Stewart, Jaclyn Smith, Joe Boxer, Route 66, Sesame Street Nine-month net income: $801 million Nine-month revenue: $13.8 billion Sears: Founded: 1893, by Richard W. Sears Headquarters: Hoffman Estates, Ill. Chairman: Alan J. Lacy CEO: Alan J. Lacy Employees: 249,000 (U.S. and Canada) Stores: Nearly 900 plus 1,100 specialty Key brands: Kenmore, Craftsman, DieHard, Lands' End Nine-month net income: -$61 million Nine-month revenue: $24.9 billion Can Kmart and Sears create a whole new kind of department store? Source: Time; 11/29/2004, Vol. 164 Issue 22, p46, 3p, 8c, 4bw Shoppers Venturing into the new supersize Sears Grand concept store in Rancho Cucamonga, Calif., off the old Route 66, can be forgiven for double-checking the name on the façade. Perhaps it's the barbecue grills on sale outside the entrance, an echo of Home Depot's parkinglot bonanzas, or the reams of DVDs, CDs and books that make you think you've stumbled into Wal-Mart. Maybe it's the colorful signs hanging from the industrial, sky-high ceiling, festooned with cheeky slogans like IT'S THE LITTLE THINGS THAT COUNT, which remind one of the king of cheap chic, Target. Then again it could be the 10-ft.-wide aisles and end-cap displays with towering boxes of bulk sodas, detergent and paper towels that look straight out of Costco, or the smarter, casual clothes that smack of Kohl's. Sure, this Sears store still has its standard array of Kenmore appliances, Craftsman power tools and DieHard batteries, but there's also a wine section and an eye-care shop. Most important, there isn't a musty, aging shopping mall anywhere in sight. If Sears' odd amalgam of its rivals' successful retailing strategies seems a bit disorienting, consumers may have to get used to it. Until now, the Grand store has been just a small-scale experiment to lure shoppers in more often and stop Sears from being squeezed by discounters on the low end and big-box specialty retailers on the high end. Think of it as the wider side of Sears. But in the wake of last week's $11 billion megamerger with floundering discounter Kmart, the Sears Grand could be the foundation of an extreme and long-overdue makeover. By melding the Sears savvy in selling so-called hard goods like dishwashers, lawn mowers and flatpanel TVs with Kmart's upmarket "soft" brands like Martha Stewart Everyday, Jaclyn Smith and Joe Boxer, the sales pitch goes, the two perennial retail losers just might create a winning formula. On the other hand, by combining two badly managed retail dinosaurs into one, wags say, the companies may simply save themselves some bankruptcy fees when they inevitably go extinct. Notwithstanding all the talk about scale, $300 million in annual cost savings and sizable purchasing power, the merger isn't so much an attempt to take on a behemoth like Wal-Mart as it is to survive in spite of it. Even with a combined $55 billion in annual sales, Sears and Kmart will be just one-fifth the size of Wal-Mart, which "is so overwhelming in terms of market share, logistics and efficiency that going up against them would be futile," as Michael Appel, managing director of Quest Turnaround Advisers, puts it. For the moment, at least, Sears and Kmart will operate as separate chains under one corporate umbrella, Sears Holdings, and each will probably offer a smattering of the other's trademark brands. But all indications are that as time goes by, Sears, the more productive store operator and the more respected brand, will subsume Kmart and try to carve out a successful niche as a middle-market power retailer focused on fashion and the home, with more attitude and style than JCPenney could ever hope to have. "We are the trade up," Sears CEO Alan Lacy said almost defiantly at the announcement of the deal. "We sell better things than Wal-Mart and Target. We've got better brands [and] better service." The shotgun marriage between Sears and Kmart is the brainchild of Kmart chairman and maverick investor Edward Lampert. A billionaire finance whiz who counts David Geffen and Michael Dell as clients and Warren Buffett as his idol, Lampert took control of Kmart when it came out of bankruptcy 18 months ago. Since then Lampert, 42, who also happened to be Sears' largest single shareholder through his ESL Investments, has turned Kmart into a cash cow, albeit a shrinking one. Although critics describe his moves as short-term fixes, he reduced inventory, slashed costs, limited discounts and sold off some of Kmart's lucrative real estate to the likes of Home Depot and, yes, even Sears. It's no wonder that so many skeptics think Lampert's latest gambit is more about real estate than retail, part of a long-term liquidation plan to unload billions of dollars' worth of property, as well as perhaps some valuable brands, to the highest bidders. But it's a notion that the notoriously reticent Lampert took pains to reject last week. While acknowledging that some underperforming stores would continue to be disposed of, he told investors, "I don't think any retailer should aspire to have its real estate be worth more than its operating business." Lampert may have no operational merchandising experience--after Yale, he worked at Goldman, Sachs under the tutelage of Robert Rubin, and went off to start his own fund at age 25 with the help of legendary Texas investor Richard Rainwater. But Lampert does have ideas about how to run a retailer, such as an unwillingness to throw money at updating stores without clear evidence of a return, and a firm refusal to play the short-term, quarterly-earnings game that Wall Street so often demands. In April, he brought in a design team led by former Gap executives to freshen up Kmart's clothing lines. "Eddie is relentless and a harder-nosed operator than most people want to believe," says Henry Miller, a leading business-restructuring adviser who worked with Kmart during its bankruptcy. "In point of fact, he is a retailer, in his mind. He will fight for a nickel, and mind every penny." (If anybody doubted how good a dealmaker or student of risk Lampert was, he proved it in January of last year, when he was kidnapped. He talked his captors, who were holding him for a $1 million ransom, into letting him go with the promise he would pay them $40,000 a few days later.) Over the past couple of decades, both Sears and Kmart have become mere shadows of themselves, plagued by aging, poorly stocked stores; management turmoil; outdated merchandise; and a lack of sophisticated IT systems--or, for that matter, a clear identity. Whereas Kmart has failed miserably to compete on price with Wal-Mart or on style with Target, Sears has found it harder and harder to stay relevant at its aging 870 mall locations, about the same number of stores it had back in 1970. It has tried everything from financial services (its "socks and stocks" period) to home improvement (the Great Indoors experiment) to returning to its catalog roots, with the purchase of the upscale Lands' End catalog, which has proved to have less broad appeal than Sears had hoped. In one key sense, at least, there is no denying that the merger is all about real estate. For years, Sears has claimed to be the prisoner of its once pioneering shopping-mall locations, where, in fact, Americans do less and less of their shopping, especially on big-ticket items. By transforming several hundred of Kmart's 1,500 freestanding and strip-mall outposts into New Age Sears stores, at an estimated price of about $3 million apiece, the company hopes it can finally reach its best potential customers. That assumes, of course, that those customers want to reach Sears. For even if Sears and Kmart can assemble a compelling assortment of exclusive product lines to sell, they are still, in a sense, "going to have to transcend their own [weak store] brands," says Kevin Keller, professor of marketing at Dartmouth's Tuck School of Business. Whether Sears and Kmart can do that by incorporating the best elements of much stronger brands in the industry remains unclear. "It could be more like a Bed Bath & Beyond meets Best Buy meets Target," says Marshal Cohen, chief fashion analyst at industry researcher NPD Group. "They've got a second chance here." But if Eddie Lampert can't make it work this time, it's likely to be their last. 1886: [SEARS] Richard W. Sears founds the R.W. Sears Watch Co. in North Redwood, Minn. A year later, he hires watchmaker Alvah C. Roebuck 1896: [SEARS] Issues its first large general catalog. Now known as Sears, Roebuck & Co., it sells dolls, bikes, sewing machines and iceboxes 1899: [KMART] Sebastian Spering Kresge, a man known for frugality, opens a five-anddime store in downtown Detroit; he calls it S.S. Kresge Co. 1925: [SEARS] Opens its first retail store in Chicago. Two years later, it launches its brands of Craftsman tools and Kenmore appliances 1945: [SEARS] Sales pass $1 billion. In 1946, anticipating demographic shifts, Sears begins to build large stores in the suburbs 1962: [KMART] Unveils its first Kmart discount department store, in a suburb of Detroit; also opens 17 other stores 1966: [KMART] The same year its founder dies, sales top $1 billion mark. In 1977, Kresge's company officially changes its name to Kmart Corp. 1981: [SEARS] To add to its financial holdings (after buying Allstate Insurance in 1931), it buys Dean Witter and Coldwell Banker 1986: [KMART] Takes over as the nation's biggest retailer, passing Sears for the first time. Loses the mantle four years later to Wal-Mart 1987: [KMART] Martha Stewart joins forces with the retailer, becoming the chain's entertainment-and-lifestyle spokeswoman 1990: [KMART] Buys the Sports Authority and a 22% stake in OfficeMax, which it increases to 90% a year later. In 1992, it acquires bookseller Borders 1993: [SEARS] A turning- point year. The Big Book catalog is discontinued; the company spins off Dean Witter in an effort to refocus on retail identity 2002: [KMART] Files for Chapter 11 bankruptcy and closes 283 stores. Under Edward Lampert, emerges from Chapter 11 a year later [SEARS] To jazz up its softer-goods appeal, the retailer acquires Lands' End, the largest specialty- apparel catalog, for $1.9 billion 2004: [KMART] Chairman Lampert, left, and Sears CEO Lacy plan an $11 billion merger to become the nation's third largest retailer