The Characteristics of the Tragic Figure

advertisement

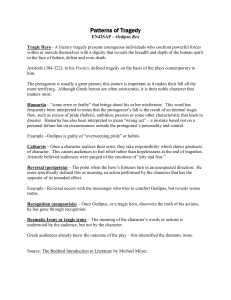

The Characteristics of the Tragic Figure The tragic figure must be responsible for his own downfall. He suffers from hubris that leads him to make hamartias or errors in judgment that precipitate his catastrophic end. Hubris: a tragic flaw in the temperament or disposition of the tragic figure (jealousy, hatred, pride, ambition) Hamartia: an error in judgment—the tragic figure makes a mistake or a series of mistakes that sets in motion the consequences that bring about his downfall. The girl in Joyce’s story is not tragic but pathetic because she is a victim of fate, of circumstances beyond her control, and not a victim or her own deliberate mistakes or errors in judgment. The tragic figure must suffer and be aware of the reasons for his suffering. It is important to realize that a tragic figure never suffers "poetic justice"; that is, he never suffers as he deserves to suffer but always more than he deserves, an idea that is perhaps best expressed by the anguished King Lear when he proclaims "I am a man more sinned against than sinning." In Joyce’s story, the girl dies instantly; she dies without suffering and without fully understanding the circumstances that lead her to her death. There must be a moment of illumination or recognition on the part of the tragic figure acknowledging that he is responsible for the tragedy that befalls him. To suffer without realizing why he suffers is to render that character more pathetic than tragic. It is for this reason that the tragic figure cannot be insane except under very special circumstances and clearly enunciated conditions. Lady Macbeth, for example, goes insane and dies by her own hand; but her madness actually heightens her tragedy rather than diminishes it because it is result of her realization of the evil that she has wrought. Her suffering is so intense that she cannot bear it, and so, her mind snaps from the pressure of her guilt. Lear, too, goes insane but only after he recognizes his errors in judgment and is forced to endure the ingratitude of his two daughters. The tragic figure suffers both physically and mentally, the anguish of the mind being, of the two, the greater suffering. We must know the tragic figure, the soliloquies in the play serving this purpose. A soliloquy, derived from the two Latin words solus meaning "alone" and loquere meaning "to speak" is a speech delivered by an actor while alone on the stage showing how he thinks and feels and indicating the reasons or motivations that compel him to act as he does. We know little about the girl from the thumb-nail sketch we are given of her and so while we feel sorry for her, we do not regard her as tragic. We must respect and admire the tragic figure and pity his downfall. Unlike us, the tragic figure is not ordinary but extraordinary; we must look up to him as being greater than we are, not regard him as our equal or as a lesser human being. Thus, we never identify with the tragic figure, for to do so would be to see him as our equal and therefore not to esteem him as highly as we should. Rather than identify with the tragic figure, it would be more accurate to say that we associate with him in that we see, on a lesser scale, some of our own traits of character, but even more importantly perhaps, we are afforded, through him, a privileged glimpse into the tragic dimensions of the human condition. To paraphrase Eliot’s Prufrock, we are not Prince Hamlet nor are we meant to be; we are, instead, all of us, attendant lords, participating vicariously through the great tragic figures of literature, in the tragedy of life. The German playwright Friedrich Hebbel put it well when he said The hell-fire of life consumes only the best among us. The rest of us sit by the fireside, warming our hands. Finally, in what is an essential response to the tragic experience, we must be left at the conclusion of the play with a feeling of waste or a sense of profound loss at the death of the tragic figure. We must, in other words, be aware of the difference between What a tragic figure has become and What he might have been and of the great loss of human potential of that tragic figure when he dies at the end of the play. It might be appropriate to end this discussion with a quotation from the eminent Shakespearean critic A.C. Bradley who articulates most eloquently the nature and greatness of a Shakespearean tragic figure: The tragic hero with Shakespeare, then, need not be "good," though generally he is "good" and therefore at once wins sympathy in his error. But it is necessary that he should have so much of greatness that in his error and fall we may be vividly conscious of the possibilities of human nature… A Shakespearean tragedy is never, like some miscalled tragedies, depressing. No one ever closes the book with the feeling that man is a poor mean creature. He may be wretched and he may be awful, but he is not small… And with this greatness of the tragic hero… is connected, secondly, what I venture to describe as the centre of the tragic impression. This central feeling is the impression of waste. (Bradley, 1966, 15-16)