The Tragic Hero

advertisement

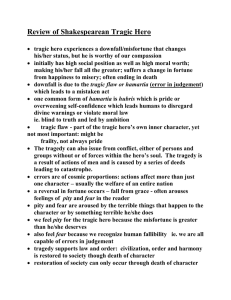

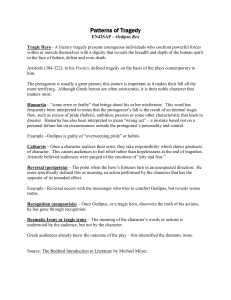

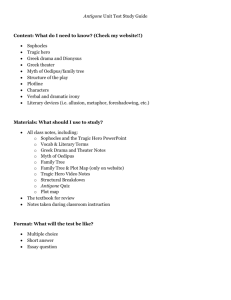

The Tragic Hero According to M.H. Abrams in his A Glossary of Literary Terms: “Aristotle says that the tragic hero will most effectively evoke both our pity and terror if he is neither thoroughly good nor thoroughly bad but a mixture of both; and also that this tragic effect will be stronger if the hero is ‘better than we are,’ in the sense that he is of higher than ordinary moral worth. Such a man is exhibited as suffering a change in fortune from happiness to misery because of his mistaken choice of an action, to which he is led by his hamartia—his ‘error’ or ‘mistake of judgment’ or, as it is often, though misleadingly and less literally translated, his tragic flaw. (One common form of hamartia in Greek tragedies was hubris, that ‘pride’ or overweening self-confidence which leads a protagonist to disregard a divine warning or to violate an important moral law.) The tragic hero, like Oedipus in Sophocles’ Oedipus the King, moves us to pity because, since he is not an evil man, his misfortune is greater than he deserves; but he moves us also to fear, because we recognize similar possibilities of error in our own lesser and fallible selves.” So, the tragic hero, according to Aristotle: Is neither good nor bad but a “mixture of both.” Is “better than we are,” in that he is of higher than ordinary moral worth. Suffers “a change in fortune from happiness to misery.” Suffers this fall because of a “mistaken choice of an action.” Is led to this mistaken choice of action by his hamartia, often excessive pride. “Moves us to pity because, since he is not an evil man, his misfortune is greater than he deserves.”