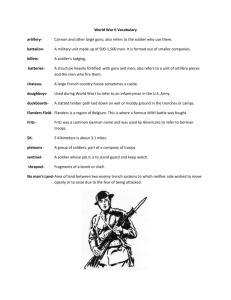

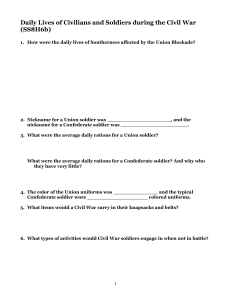

SECTION 3-------

advertisement

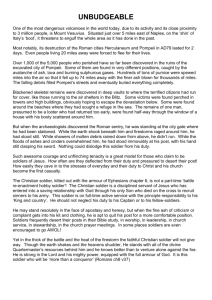

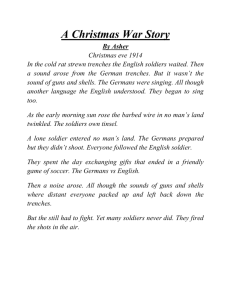

Generals Die in Bed by Charles Yale Harrison Teaching notes prepared for VATE members by Robert Cole CONTENTS 1. Introduction Page 1 2. Ways into the text Page 6 3. Running sheet Page 8 4. Characters Page 12 5. Issues and themes Page 16 6. A guided approach to selected passages Page 18 7. Further activities for exploring the text Page 22 8. Key quotes Page 25 9. Essay topics Page 29 10. References and resources Page 30 References in this guide are to Harrrison, Charles Yale, Generals Die in Bed, Penguin 2003 Purchasers may copy Inside Stories for classroom use VATE Inside Stories – Teaching Notes Section 1. An introduction to Generals Die in Bed. First thoughts Generals Die in Bed is a powerful novel, which vividly conveys the experience of the common soldier in World War One. Its title, part joke, part outrage, signals the author’s intention as polemical. The author creates a barren landscape, destroyed by war, and the characters inhabit this wasteland. The characters are seen fleetingly, in particular moments only, and we divine what they are feeling mostly through their actions. The story is punctuated by vivid descriptions of trench warfare, description of rest periods, and of the discomfort and danger of life in the trenches. Generals Die in Bed is told by a soldier with no name, and the reader sees the war through his eyes. Charles Harrison creates a character who sometimes sees like a journalist and sometimes sees like a poet. The soldier’s vision extends beyond his immediate experience to register and respond to the whole extent of human suffering that the war creates. Like Wilfred Owen, in Dulce et decorum est, Harrison’s intention is to awaken his readers to the new reality of War. The opening chapter portrays the new soldiers leaving Montreal for the first time as lost, unhappy and childish in their attempts to blot out their fears of what is to come. The parade to the train station is described in a series of fragmented images, in an atmosphere of bewilderment and degradation. From then on, the novel takes on the grinding, disciplined structure of military action followed by periods of rest. This structure helps to convey the unremitting sameness of war, and to enact the soldiers’ sense of unrelenting danger and boredom. The soldier is able to see and respond to the suffering around him. He can see the humanity of the enemy, and remember and feel anger at the slaughter of the surrendering Germans. Like Owen he is a witness to the outrage. The soldier sees both suffering and cause and in the act of seeing frees himself. Context of World War I World War One was the most horrifying conflict in world history, killing many millions more than the war of 1939-45. It was fought between the Allies, (France, Britain and its Empire, and Russia), against the Central Powers of Germany, and the crumbling empire of Austria-Hungary. In 1917, the new Bolshevik Government in Russia capitulated to Germany, freeing it to fight on one less war front than before. Unfortunately for Germany, the entry of the USA into the war in 1917 more than nullified this new advantage, and proved decisive in the Allies’ gaining victory in November 1918. World War One was new in that it was, up to that time, the most mechanised war in human history. Human science and technology, the engineers of nineteenth century industrial progress, the glorious products of the Enlightenment, were turning to the job of killing to make it more efficient than ever before. Although, in 1914, as mentioned in The Great War and Modern Memory (Fussell, 1975), the word ‘machine’ had not been coupled with the word ‘gun,’ the killing capacity of the armies hugely increased in a short time, so that human heroism became largely irrelevant to the outcome of war. With the entry of the USA into the war, the Allies’ greater industrial capacity proved decisive. VATE Inside Stories -Teachng Notes Generals Die in Bed 1 The War in France and Belgium was fought across a huge front stretching right across the centre of France. This was trench warfare. It consisted of a series of huge artillery bombardments on enemy soldiers sheltering in the trenches, followed by advances on the opposing trenches. The troops faced systematic machine gun and artillery fire sweeping over the land each time they advanced. Such was the intensity of the fire, that often only remnants of whole military units would survive an attack. The casualty statistics were unprecedented: the British lost 20,000 soldiers in the first three hours of the Battle of the Somme. The war was one of attrition. One side outlasted the other because of their superior numbers, superior firepower and a superior capacity to supply their troops. The Literary Context Generals Die in Bed is part of an enormous body of literature on World War One. The literature includes works of protest, works that express loss of faith in civilisation and in the idea of human progress, and works that see the world of Edwardian England as a time whose moral and intellectual security has gone forever. The literature of World War One tries to find ways to convey the new experiences of war and a new sense of alienation, both from authority and from earlier notions of the glory of war. War as grandeur In the nineteenth century, War was seen as a supreme opportunity for the expression of nationalistic fervour. Nikolai Rostov gives passionate expression to this emotion in this extract from War and Peace: Through the flourish of trumpets the youthful, gracious voice of the Emperor Alexander was distinctly heard, uttering some words of greeting and the first regiment’s roar of ‘Hurrah’ was so deafening, so prolonged, so joyful that the men themselves felt awestruck at the multitude of their members and the immense strength they constituted. Rostov, standing in the foremost ranks of Kutuzov’s army, which the Tsar approached first, was possessed by the same feeling as every other man there present – a feeling of self-forgetfulness, a proud consciousness of might, and passionate devotion to the man round whom the solemn ceremony was centred. One word, he thought, from this man and this vast mass (myself an insignificant atom, with it) would plunge through fire and water, ready to commit crime, to face death or perform the loftiest deeds of heroism. (p. 238) Similar enthusiasm, similar sentiments and similar imagery appear in the following poem, Peace, by Rupert Brooke: Now, God be thanked Who has matched us with his hour, And caught our youth, and wakened us from sleeping, With hand made sure, clear eye, and sharpened power, to turn as swimmers turn into cleanness leaping… (Men who march away, ed. by I.M. Parsons, p. 40) War is a release from the mediocrity, the greyness and moral compromises of life. The speaker of the poem finds release, and peace of mind in the contemplation of action. VATE Inside Stories -Teachng Notes Generals Die in Bed 2 In Brooke’s poem, The Soldier, the ‘self-forgetfulness’ mentioned by Rostov becomes the complete subsuming of personality, of self, in death, into identification with the nation: If I should die, think only this of me That there’s some corner of a foreign field That is forever England. There shall be In that rich earth a richer dust concealed; A dust whom England bore, shaped, made aware, Gave once her paths to love, her ways to roam A body of England’s, breathing English air Washed by the rivers, blessed by sons of home. And think, this heart, all evil shed away A pulse in the eternal mind, no less, Gives somewhere back the thoughts by England given; Her sights and sounds, dreams happy as her day, And laughter, learned of friends, and gentleness In hearts at peace, under an English heaven. In this poem, the surrender of personality and of individual agency seems complete. What is absent is any sense of suffering, or any awareness of the cost of such suffering. Wilfred Owen’s Poem Dulce et decorum est, in which Owen writes of the effects of mustard gas, is perhaps the most famous rejoinder to these sentiments: In all my dreams, before my helpless sight, He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning… …If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood Come gargling from the froth corrupted lungs, My friend, you would not tell with such high zest To children ardent for some desperate glory, The old lie: Dulce et decorum est Pro patria mori. The poem makes the Latin quotation bitterly ironic. Owen holds before his readers’ eyes the image of ghastly, undeserved suffering, an image that has nothing to do with heroism. This ‘plunging’ is desperate, undignified, unheroic, pitiable. The cost of the soldier’s sacrifice seems too great. The Literary Response to the War. World War One saw the emergence of many fine poets who, in confronting such horror, needed to free themselves from the beliefs and habits of expression of the past. Isaac Rosenberg, Edmund Blunden, Siegfried Sassoon, and the most famous, Wilfred Owen, gave voice to powerful feelings of bitterness, betrayal, disillusionment and grief. They wrote of appalling miscalculation, life in the trenches, the loss of innocence, the awareness of lost opportunity, the hideousness of human suffering, the wounded, the ‘mental cases’ and the ignorance of the people at home. These themes were later given expression in the prose works of the war, such as Goodbye to All That, Memoirs of a Fox Hunting Man, Memoirs of an Infantry Officer, Sherston’s Progress, and in the most famous novels of the war, A Farewell to Arms and All Quiet on the Western Front. VATE Inside Stories -Teachng Notes Generals Die in Bed 3 A Farewell to Arms A Farewell to Arms expressed rage and bitterness at the waste of human lives in a world gone mad. The characters live from moment to moment, trying to shut out the overwhelming madness and sorrow of the war, seeking to find happiness in personal commitment only. Hemingway’s tough prose, which worked by understatement, plainness and brevity, became a model for a generation of American followers. They were small grey motor-cars that passed very fast; usually there was an officer on the seat with the driver and more officers in the back seat. They splashed more mud than the camions even and if one in the back was very small and sitting between two generals, he himself so small that you could not see his face but only his cap and his narrow back, and if the car went especially fast, it was probably the King. He lived in Udine and came in this way nearly every day to see how things were going, and things went very badly. At the start of the winter came the permanent rain and with the rain came the cholera. But it was checked and in the end only seven thousand died of it in the army. (p 10). Unlike the Emperor Alexander in War and Peace, the King is an utterly insignificant figure, smaller than his guards, hiding from the action and only viewing it from afar. The scale of human devastation, the scale of the war itself, has destroyed any notions of imperial, nationalist grandeur. The phrase ‘only seven thousand,’ is the final shocking testament to the great change in people’s expectations - the word ‘only,’ presenting the reader with a new way of counting the cost of war. All Quiet on the Western Front All Quiet on the Western Front is the most famous German novel about World War One, and, like Generals Die in Bed is told from the point of view of a German soldier. Both books were published in 1928. Remarque's novel follows a group of young men who were in the same class at school before enlistment. It differs from the Canadian text, not in the incidents, themes or issues it explores, but in its development of more rounded characters, and in the creation of German civilian life, both before and during the war. Paul, the main character, experiences similar feelings of alienation to the soldier in Generals Die in Bed, but the novel gives more time to Paul’s reflections, and is more interested in his experiences: I go back home and throw my uniform into a corner. I had intended to change it in any case. Then I take out my civilian clothes from the wardrobe and put them on. I feel awkward. The suit is rather tight and short. I have grown in the army. Collar and tie give me some trouble. In the end, my sister ties the bow for me. But how light the suit is, it feels as though I have nothing on but a shirt and underpants. I look at myself in the glass. It is a strange sight. A sunburnt, overgrown candidate for confirmation stares at me in astonishment. (pp. 163-164) This passage is a poignant reflection on how Paul has changed, and how the old familiar self, relationships and attachments have become strange to him. He is a character whose war experiences have made it impossible for him to re-enter his old life. His suffering has the quality of tragedy. VATE Inside Stories -Teachng Notes Generals Die in Bed 4 All Quiet on the Western Front, while polemical in intention, tries to create a recognisable world - the scene above is a scene from a realist novel. Paul’s world is peopled with his family, old memories, past experiences. Yet the War is now a part of that old life, a life that is disappearing. Like Robert Graves, like Siegfried Sassoon, for Paul, a world is passing away. Generals Die in Bed. Unlike All Quiet on the Western Front, Generals Die in Bed is a book from the new world, from Canada, rather than from the old world of England or Germany. World War one was, for Canada as it was for Australia, a nation-defining experience. It is all the more noteworthy, then, that Generals Die in Bed makes almost no reference to Canadian society and no reference to the soldier’s family. In spite of the close similarity of themes and incidents between the two books, Generals Die in Bed is not a realistic novel, but instead has the flavour of journalism, poetry, polemic and film. The story is told in the first person, and in the present tense. The incidents are ‘directly observed.’ The world of the story is the first-hand experience of the soldier-narrator, which at times has the quality of nightmare. The consequence of this ‘narrowness of vision’ is a loss of complexity in characterisation, but a gain in poetic intensity. Like Wilfred Owen, ‘In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,’ the soldier ‘sees,’ and the reader is forced to respond to intensely visual imagery of human suffering and degradation, so that he will see, too. The soldier has a poet’s vision which sees beauty in the midst of destruction and humanity in the face of the enemy. In his actions and in his responses, he brings compassion to the nightmare world, which becomes a touchstone in our judgment of events. VATE Inside Stories -Teachng Notes Generals Die in Bed 5 Section 2. Ways into the text Before studying the book Teachers may like to prepare a short quiz on World War One to test the students’ background knowledge. Some questions could be: 1. When was the First World War fought? 2. Which countries were involved? 3. Where was the war fought? 4. When did the USA enter the war? 5. Who won and why? 6. How was the war fought? 7. How was this war different from previous wars? 8. What was life in the trenches like? 9. How did the general populace react to the war? 10. Why were the generals the targets of so much criticism? Teachers may like to look at www.library.georgetown.edu-dept-speccollamposter.htm to view a huge collection of recruiting posters. Some could be selected and analysed for their assumptions, their pictures of the enemy, and their persuasive techniques. Students could prepare a short creative piece on the photograph on the cover of the book The Great War and Modern Memory which can be accessed at www.lib.byu.edu/~english/ww1/critical/html. The picture is of a young man, perhaps a boy, in a uniform too large for him and with an expression of grief and sorrow. 1. Students could be asked to notice his stance, his uniform, his facial expressions and his surroundings. 2. They might be invited to imagine how old he could be, what has recently happened to him, 3. Before writing, they could read page 95 of the text (the passage where the soldier imagines the mother of the two German soldiers), then have him thinking of what he has left behind. Using the following website, www.bbc.co.uk/history/war/wwone/index/shtml, students could make use of the video, 3D, and interactive packages available at the site, such as 1. The animated history of the battles of World War One. 2. The videos on the life of the soldier at war, with topics such as ‘Going over the top,’ 3. The virtual tour of a trench. 4. Slide shows of World War One photos with accompanying diary extracts 5. Articles which debate contentious topics such as the role of the generals 6. Readings of World War One poems, including those of Wilfred Owen. The danger of this website is that its fascination is so great that students may find it distracting. VATE Inside Stories -Teachng Notes Generals Die in Bed 6 Introducing the book. Perhaps the best way of getting into the text is to confront some of the difficult war experiences through some of the poetry of the time. The following poems are from the volume Men who march away. 'Base details': Siegfried Sassoon If I were fierce, and bald, and short of breath I’d live with scarlet Majors at the Base, And speed glum heroes up the line to death. You’d see me with my puffy, petulant face, Guzzling and gulping in the best hotel, Reading the Roll of Honour. ‘Poor young chap,’ I’d say--‘I used to know his father well; Yes, we’ve lost heavily in this last scrap. And when the war is done and youth stone dead, I’d toddle safely home and die--in bed. How is the officer presented in the poem? Comment on words like ‘scarlet', ‘guzzling and gulping', and ‘toddle'. What does ‘glum heroes’ mean? Why does the major call a battle a ‘scrap?’ This poem is useful, in that it is a direct and obvious attack on those in charge of the war, heavily satirical, something that our book is not. It is interesting to note that when the soldier says, ‘hell no, generals die in bed’ (p. 112), the statement is delivered as if it were a simple fact, part of the universe. 'The General': Siegfried Sassoon ‘Good–morning; good-morning!’ the General said When we met him last week on our way to the line. Now the soldiers he smiled at are most of’ em dead, And we’re cursing his staff for incompetent swine. ‘He’s a cheery old card,’ grunted Harry to Jack As they slogged up to Arras with rifle and pack. But he did for them both with his plan of attack. How are Harry and Jack presented? What does the general’s cheeriness suggest about his grasp on the reality of war? The poem is written in very colloquial English. Why? VATE Inside Stories -Teachng Notes Generals Die in Bed 7 Section 3. Running sheet Chapter 1 Recruits Chapter 2 In the Trenches Chapter 3 Out on Rest Chapter 4 Back to the Round ‘Down the line.’ The degradation that comes with the anxiety of waiting. ‘Walking to the train,’ Writer alienated from the celebrations..only feels something when a girl pays him attention. The moment of leaving Celebrations finish soldiers left alone on the station ‘in their own vomit.’ The physical discomfort of Fry’s difficulty in keeping up, the trenches, captain’s Captain’s attempt to humiliate contempt for human frailty. him. The imagined battle In the quiet, which makes him nostalgic, he imagines battle details at some leisure The first bombardment Utterly surprising, haphazard, terrifying and completely destructive of any previous composure he possessed. The lice Invasive, tormenting, degrading and debilitating The meaning of ‘rest’. Meaningless training activities Petty cruelty of officer. Clark punishes Brown Passing the time. Hearing about Martha, drinking, pack drill, a sense of the futile. The difficulties warfare of trench The stench, the wet, the barrenness, danger of snipers The German sniper His position, how he goes about his work, How he will be killed. The sharing of the food Ordinary things go on Shooting of Brown Chapter 5 On Rest Again The precision of the shooting, the matter-of-fact response, the sharing of Brown’s rations Germans attack a supply Confusion, panicking of the road horses, Failure of command, horses attack lorry driver VATE Inside Stories -Teachng Notes Generals Die in Bed 8 Chapter 5 On Rest Again (cont.) Chapter 6 Bombardment Marching Seeing ruins of houses, Poplar trees. The smell of growing beans, memories of Brown and wife Arriving at the Rest place. ‘no shells, no trenches’ Waking and making it home Rumours good and bad The Estaminet Over-eating and drinking, following two girls, becoming incoherent, moved on by MPs After drill Story of girl who bestowed favours for a tin of Bully Beef The swimming in the stream The bloated body of the soldier. No esprit de corps in the Two attack each other twice over trenches a piece of bread. Men exhausted preparations for battle from German gunners getting closer and closer, candle goes out, Futile attempts at conversation. Terror of shellfire Writer’s sense of the futility of trying to propitiate ‘an insane god,’ “selfish fear stricken prayers.” Lack of interest in any news Anderson’s prediction of the end of the war of the war Call for brigade Chapter 7 Bethune volunteers for Running to trench, diving in bayonet stuck, abandons gun, Returns to shoot German, takes two prisoners, a hero’s welcome, A powerful emotional reaction to what he has done, later. An ugly but joyful haven A haven because it is free from the sounds of battle. Bawdy marching songs Raw energy of the soldiers versus Anderson's moralising The guard of honour The emptiness of the ceremony, its irrelevance to the soldiers. The shower and change of Lice lurking in the clean clothes clothes Staying home. at the peasant’s Soldier shows humanity to peasant, is rewarded with his daughter for the night. Looking forward to London. VATE Inside Stories -Teachng Notes Generals Die in Bed 9 Chapter 8 London Arrival Meeting Gladys Gladys is a prostitute who gives The men on leave a good time Visit to the theatre Soldier angered by performance and alienated by audience and its responses Gladys’s room Her knowledge of what men need, her skill and compassion. His joke about committing Gladys does not understand the murder seriousness of what he is saying. Meeting with the curate Chapter 9 Over the Top Curate’s naïve ideas laughable when compared with soldier’s experience. Soldier’s emotional isolation. Parting from Gladys Simple poignant farewell Preparations for new offensive and arrival of new recruits Renaud’s suffering and Soldiers' compassion contrasts Clark’s treatment of him with Clark’s violent contempt Attack - ‘Advancing behind Slowness and steadiness of the the sheet of flame’ advance Death of sniper Uselessness of asking for mercy - complete absence of pity in Canadian soldiers Rain and its effect Suffering of the horses Counter-attack Ferocity of battle, transforming soldier into state of frenzied hatred, piles of dead enemy, blown to pieces by own shells Flame–throwers Renaud shot by Broadbent Death of Clark Shot by Fry Retreat trench Chapter 10 An Interlude back to original Fry’s legs ‘torn from under him’ Abandoned. Nothing gained from the attack. ‘a neat village’ Soldier and Broadbent in same billet. Soldier’s foot cared for by old lady. Receives kindness Soldier gains promotion to corporal VATE Inside Stories -Teachng Notes Generals Die in Bed 10 Chapter 11 Arras Address to troops by division Meaninglessness of speech to commander soldiers Soldiers put into convoys of Soldiers discuss cost of war and trucks who profits from it. No food or provisions for Conditions for soldiers bad three days Chapter 12 Vengeance Arrival in the city of Arras Place deserted, provisions but full of The looting Complete breakdown of discipline, including officers, raiding of churches The shelling by the Germans Sudden ending of riot Next day more mayhem Discussion in the trenches On the futility of war Broadbent feels need to bring mutinous talk to a halt Learning ‘infiltration’ tactics Hardening of the troops Llandovery Castle speech Designed to make the troops pitiless Soldier’s ears bleed from the noise. Shooting of the surrendering Pitiable Germans contrasted with Germans inexorably ‘revenging’ allies The beginning of the attack The wounding of the soldier His relief that his war is over Death of Broadbent Lost his leg and dies calling for his mother. The protest of the German Demands to be moved to an officer officer’s car Llandovery exploded VATE Inside Stories -Teachng Notes Castle myth Soldier remembers the speech and sees again the images of the surrendering Germans Generals Die in Bed 11 Section 4. Characters All the characters in Generals Die in Bed are lightly drawn. Each character represents a different possibility of response to the situation of war. The narrating soldier as storyteller The narrating soldier is the dominant character. We see all the action through his eyes, and nothing occurs in the novel to encourage the reader to question his authority. In scene after scene his response guides our response. Although the reader is occasionally aware that the vision of the soldier is partial, we never question his authority, because he speaks with the voice of compassion. He notices where others do not, and acts in compassion. His different responses make up the guiding rhetoric of the novel. ‘A thousand thundering orders! A thousand trivial rules, each with a penalty for infraction, has made will-less robots of us all. All, without exception…’ (p. 47) ‘Who can describe the few moments of peace and sunshine in a soldier’s life?’ (p. 69) ‘Our lips tighten. Our eyes open wide. We do not talk. What is there to say?’ (p.75) ‘To think we could propitiate a senseless god by abstaining from cursing!’ (p. 81) Who can comfort whom in war? Who can care for us, we who are set loose at each other and tear at each other’s entrails with silent, gleaming bayonets? (p. 95) Back home our lives were more or less our own – more or less, there we were factors in what we were doing. But here we are no more factors than was the stripling Isaac whom the hoary senile Abraham led to the sacrificial block… (p. 105) We are invited to respond sympathetically, and we do. The soldier as character The soldier is sensitive to the suffering men around him. He supports both Renaud and Fry in their first forays to the front. He is aware of the inestimable value of kindness. In sharing his tobacco, he makes the old peasant and his daughter so grateful, they arrange for him to spend the night with the daughter. The soldier is kind to the German who is Karl’s brother. In allowing the brother to take the papers, he allows him a moment to grieve, to give his brother a moment of a ‘funeral rite.’ When the three of them run across the no man’s land, they have a bond – three soldiers, without a name, running across a wasteland. For a short time they belong nowhere and to no one but each other. In London the soldier is fortunate to meet a warm and affectionate prostitute, who cares for him in every way he needs. But he finds the ignorance of the Londoners about the reality of the war, outrageous. He feels a huge gulf between himself and everyone else. VATE Inside Stories -Teachng Notes Generals Die in Bed 12 As the war progresses, the soldier becomes harder. In the final battle, the soldier is still able to register the humanity of the surrendering Germans, but he is steeled to ignore it. ‘the hands shake eloquently, asking for pity. There is none.’ It is only when he hears that the tale of the Llandovery Castle was a lie, that he can feel the human responses he was suppressing in the fighting, that of rage: rage at the coolness and callousness of the authorities, and pity for the Germans he and his comrades murdered. Questions: 1. Examine the language of the quotations above. What are they meant to make you feel and how do they do they try to achieve it? 2. in what way was the soldier brave when he was in the trench with the Germans? Why does he have such a passionate reaction to the experience at the end? 3. Find examples in the final chapter that show the hardening of the soldier and the troops taking place. 4. Why is it so important for the soldier to remember and to continue to see ‘the clasped hands silently asking for pity? Other Characters The soldiers: The soldiers are lightly drawn, some appearing in only a few scenes. They are created in only a few moments and actions. Their lives are suggested, and perhaps are all the more poignant. Anderson: the middle-aged balding preacher, who, at the beginning, sees himself as the appointed moral guardian for the men. Even at the height of the shelling, he is complaining at the cursing of the men. The soldier’s experience of shelling makes the hellfire threats of the preachers seem empty and insignificant. Anderson is too shy to undress in front of the men at the Somme River. He believes he can predict the end of the war by reading the Book of Revelation. His faith does not reassure him. At the height of an attack he ‘jumps from his gun and lies grovelling in the bottom of a shallow trench.’ (p. 151) Nor in the end does his faith save him. He gets lost in the woods, and no one tries to find him. Question: What purpose does Anderson serve in the story? Fry: a timid man who manages to last almost for the full duration of the war. He is bullied by the Captain, Clark, but is supported by the soldier. He learns to dodge snipers; he shares the moment in the river. He congratulates the soldier on his bravery. In his last action, he says goodbye to the soldier because he believes he will not survive this action. He is wounded in the arm, and, when threatened by Clark with a revolver he shoots Clark in the back. His legs are blown off and he dies lying in no man’s land, bleeding to death. Question: What has happened to Fry to make him shoot someone on his own side? Just before he dies, how does he perceive the war and the Germans? Clark: the officious and bullying captain, who threatens Fry with a bayonet up his backside; who picks on Brown and makes him do pack drill because his uniform has VATE Inside Stories -Teachng Notes Generals Die in Bed 13 been torn by barbed wire; who bullies Renaud because he is in pain. He is shot in the back by Fry after threatening him with a revolver. Question: How would Clark justify his actions? What does it say about army discipline that a bully is made a captain? Cleary: One of the soldiers closest to the soldier. With him from the beginning, he survives the first shelling attack. He teases Brown about his wife, but after Brown’s death, feels sorry he did it. Broadbent attacks him over the dividing of the bread. He discovers the rotting corpse in the River Somme. The soldier leaves his papers with Cleary before the attack in which he took the prisoners After he returns, he looks for Cleary, but discovers he has been mortally wounded. It is as if the experience in the trenches has made the soldier more capable of feeling. Cleary’s death forces the soldier to ask questions about the meaning of all the slaughter, and then to decide: ‘better to live like an unreasoning animal.’ Question: How does the image of the men fighting over the bread make you feel? Why do they fight over something so meagre? Brown: the most pathetic, most clearly drawn of the soldiers. He takes the boots from a rotting corpse, because ‘his heel was as raw as a lump of meat.’ Brown is tall and awkward, and cannot avoid the barbed wire. His uniform made of poor quality material, tears easily. Brown glares at Clark when being reprimanded, and is put on pack drill. He is a farmer’s son and does not grasp ideas easily, so he is ridiculed by his mates and hated by Clark. He is goaded by the men, to talk about his two weeks of married bliss with Martha, his wife. As the soldier says: ‘We have heard every physical and emotional foible of Martha’s.’ Brown is shot by a sniper and killed instantly. His death does not stop the dividing of the food, which now includes the food in Brown’s haversack. His death is the only one talked of later in the novel by the men, who feel some guilt at how they treated him. Question: Generally, why do men like Brown become targets for men like Clark? Broadbent: A lance corporal who becomes a sergeant. Slightly officious. Starts playing the favourite wishing game of the men. He takes the food from the Brown’s haversack after he dies. He attacks Cleary because he believes Cleary is cheating with the bread. He has the presence of mind to shoot Renaud after he has been hit by a flamethrower. He is with the soldier in Arras and in the final battle at Amiens he and the soldier are the only two left of their company. He dies from loss of blood calling for his mother after he loses his leg at the knee. Question: Why does Broadbent express similar sentiments as he is dying, to those that Fry expressed before his final battle? Gladys and the Curate: These two characters appear only in chapter eight and exist to throw the experience of the war into some relief. Gladys is a warm-hearted prostitute who cares for the soldier. She cares for all his needs and feels for him when he is distressed. Yet, when he is distressed by the show at the theatre and by the audience as well, she does not understand. When he tells her he has murdered someone, she also does not understand the human truth behind the joke. The Curate, who greets and honours the soldier, also cannot be made to understand how the soldier feels. Wrapped in the bubble of his own fantasy of the war, he freely VATE Inside Stories -Teachng Notes Generals Die in Bed 14 contradicts someone who has been there. The soldier decides that there is no use in trying to tell him the truth and withdraws. The Curate represents all that is ignorance and complacency on the home front, but Gladys seems to represent all the soldier’s needs. Discussion topic: Compare the departure at the train stations in chapter 1 and chapter eight. Try to describe and contrast the different emotions present. Conclusion: Although there is no opportunity for the reader to see into the minds of the characters, there is evidence that they suffer from the effects of war. Fry, who was so capable of enjoying the blossoming beans, has become able to kill Clark, and to hope for death; Anderson, who in the past, prayed through a bombardment, lets go his gun and grovels at the bottom of the trench. He becomes lost and does not return. Perhaps he has lost his faith. The soldier, who could imagine the feelings of the mother of Karl, his dead enemy, and who cried after the death of Cleary, registers no emotion at witnessing the agony of Fry’s death, and is able to kill the surrendering soldiers. These changes are shown, but not explored or commented on. Yet they point to a hardening of the soldiers, to a loss of humanity, and a sense that they suffer in common. VATE Inside Stories -Teachng Notes Generals Die in Bed 15 Section 5. Issues and themes The extreme suffering of war Destruction The horrifying deaths of Fry and Broadbent and the sniper shooting of Brown, are grim in the extreme. The drawn-out, partly botched killing of Karl, the German, is almost comic, it is so grotesque. The moving curtain of artillery fire, behind which the soldiers advance their ears and noses bleeding from the shock of the explosions, has a nightmarish quality that the soldier says is worse than any traditional images of hellfire. The sight of the surrendering Germans being mown down from point blank range, their hands raised in silent pleas for pity, conveys the ruthlessness of war and the effect of the hardening of the soldiers against pity. Find other images of war’s violence and destructiveness. Watch the film A very long engagement, especially for the scenes of trench warfare. How dangerous does trench warfare seem to be? The impact on the soldiers of such danger Soldiers are so overwhelmed by their experiences that survival becomes all-important. The soldier, who has been with Fry throughout the war, leaves him to die without his legs. In chapter two, when the bombardment moves somewhere else, the soldiers feel no compassion for others being shelled, only relief that they are no longer targets. Anderson, who has also been with them throughout the war, is lost and no one cares to look for him. Then there is the complete loss of composure under fire. The soldier in panic, loses control of his bowels, and starts to pray to a God he does not believe in. Anderson, who does believe, loses his faith and grovels in the shallow bottom of the trench. Fry, in rage, kills his commanding officer, and the death is hardly registered in the story. When the soldiers are stationed in Arras without food for a number of days, they surrender to immediate need and loot the city. Once the looting starts it becomes an orgy of over eating and drinking. The soldiers making themselves sick in the process. Fires are started and shots ring out. When their appetites are sated, they become malleable again, and the generals resume command. The soldiers are so brutalised by the war that they can become capable of almost anything. Research the Battle of Brisbane during World War Two. What similarities can be seen between it and the looting of Arras? Comradeship Australian war stories are full of tales of comradeship under fire and in the extreme conditions of war. The story of Lt.-Col. (Weary) Dunlop carrying the responsibility of an entire prison camp is an outstanding example of heroic leadership and the support of his troops. In this novel, comradeship and support exists, but does not seem enough to save the men. Anderson goes missing, and no one seems to care. We see the soldier supporting Fry and Renaud. We see him weeping for Cleary. We see the men respectfully covering Brown’s body. These acts are comparatively isolated. The violence over the distribution of bread is an act of despair, that shows how the distressing feelings of need overcome any loyalty, so that the bond between the men is not enough to protect them from descending to violence against each other. VATE Inside Stories -Teachng Notes Generals Die in Bed 16 Use the Australian War Memorial website to research the stories of Simpson and his donkey and that of Weary Dunlop. Why are these people so famous? Why do you think there are no comparable stories of heroism in Generals Die in Bed? Power. In war, the Command holds almost complete power over the rank-and-file soldier. This power enables those in charge to create a situation, which in ideal circumstances, is safe for everyone. There is no mutiny; there is no answering back; there is only one voice to obey. Just as power can be used to create harmony, it can be abused to dehumanise people, to deny and remove individuality, and to ignore pain and suffering. Consider how power is used in Generals Die in Bed, using the following incidents as starting points: Fry’s attempts to scramble up the trench – Clark’s sadistic reply. Brown being forced to undergo pack drill for being clumsy. The German soldier whose breath smells of ether. Being left in Arras with no food. The false tale of The Llandovery Castle which cause the soldiers to attack so ruthlessly. Isolation The journey from Montreal in Canada to the trenches in an unspecified location somewhere in France or Belgium ‘on the front,’ is long. Equally long, and equally unspecific, are the journeys, by foot. Train or truck, between trenches, and between periods of fighting and rest. The soldiers exist in a series of locations, separated from their families, friends and homes. In the book, there is little sense of ‘home.’ We know that Brown had been a potato farmer on King Edward Island and that he was married to Martha; we know that Cleary had been a clerk in an office. These scraps of knowledge only intensify the sense we have of the isolation of the other soldiers. The soldiers are isolated in the trenches, relieved only by the delivery of rations. They are at one stage a group of five – and we know all their names, except that of the narrator. As each dies, new names are not introduced; the soldier inhabits an increasingly anonymous world. In periods of rest, the soldiers live in temporarily deserted barns, half-empty villages, and eventually Arras, which they mindlessly destroy. In his first offensive, the soldier is left alone in the trench with a German soldier; alone without his rifle, alone with someone dying, and finally alone in the wasteland between the two fronts with his prisoners. Even the tentative relationship between these three is abandoned when he hands his prisoners over to be questioned. Consider how this sense of isolation is shown throughout the book. What effect does it have on the soldier’s actions? How do images of loneliness such as the drowned French soldier in the Somme River, the narrating soldier in the theatre in London affect the increasing sense of isolation and of anonymity as the story progresses? What other images of isolation can you find? VATE Inside Stories -Teachng Notes Generals Die in Bed 17 Section 6. A guided approach to selected passages The aim of these questions is to enable students to become aware of the ways the language of the text is creating and directing their responses to the terrible incidents portrayed. The discussion question aims to help students to use their detailed understandings to inform a broader discussion. Passage 1. Ch. 1. pp. 14-7 The passage begins: ‘Our train is to leave Bonaventure Station at night,’ and ends with the end of the chapter. In this passage, the army is about to leave Montreal. From whose point of view is the scene of the march to the station described? Find two examples to support your opinion. In what state are the men? Find three statements, which describe them, and comment on how they are portrayed. How involved are the men in the celebrations? Find evidence to support your view. How are the onlookers described? Find three examples. How much understanding of the importance of the occasion for the soldiers, do the onlookers show? What effect do the crowd and the girl have on the soldier? What happens to his state of mind? How are the men on the train described? How are we invited to feel about these men? Why? Discussion question: why do you think the book begins in this way? Passage 2. Chapter 2 Pages 23-28. The passage begins: ‘I try to imagine how an action might start’ It ends with: ‘We lie still, waiting……….’ In this passage the soldier tries to prepare him for an artillery attack by reflecting on what he has been told, and imagining such an attack. He is then faced with a real one. Try to describe the soldier’s state of mind before the artillery attack begins. How is he thinking about an attack? In his imagination, how does he behave? Why is the rat so well fed? As the attack begins, how are the conditions in the trench described? What is literally meant by ‘the night whistles and flashes red?’ Who sees ‘mud and earth leap into air'? What is being referred to? VATE Inside Stories -Teachng Notes Generals Die in Bed 18 ‘A blinding flash and an exploding howl a few feet in front of the trench. My bowels liquefy'. What has happened to the soldier? What kind of response has he had to what happened ‘a few feet in front of the trench?’ How does the soldier feel about hearing the shelling half a mile away? How has the attack changed him already? After being thrown into the air, his state of mind is such that he starts to pray, even though he does not believe in God. What does he feel when he remembers that he doesn’t? Discussion question: How has the shelling changed the soldier? Passage 3. pp. 47-49 The passage begins: ‘Half a mile from our partly exposed trench, hidden in the hollow of a tree, sits a sniper…’ and ends: …we face each other with grey, sheepishly smiling faces.’ This passage is about the sniper – how he will die, his effect on the lives of the soldiers in the trenches. What kind of life does the sniper have? Why does he get extra rations? How safe is the sniper from attack? How will the sniper behave when he is caught? What will be the effect of what he says on the opposing soldiers? Why won’t the men spare his life? What happens to the men as they kill? What effect does the presence of the sniper have on the soldiers as they go about the trench? What do they do when he fires? What do the words ‘flop’ and ‘grovelling’ suggest about the soldiers’ states of mind? Why are the faces of the soldiers sheepish and smiling? Discussion questions: Why do you think the author gives us this passage before Brown is shot? When the death of a sniper occurs later, do you feel anything for him? Passage 4. pp. 88 – 95. This passage begins with the lines: ‘Something moves in the corner of the bay.’ And ends with ‘ ..tear at each other’s entrails with silent gleaming bayonets?’ Why does the soldier ‘become insane?’ What does this phrase mean? How are the soldier and the German cooperating? What is the bayonet doing to the German? Read page 89 carefully. What terrible traumatic experiences is the soldier having, one after the other? Make a list. For example he is kicking a wounded man. What else? So, why does the soldier run away? Why do ‘the horrible shrieks’ disturb the soldier so much? VATE Inside Stories -Teachng Notes Generals Die in Bed 19 How are the two other prisoners described? What does the description attempt to make you feel? What do ‘the eyes of a dog’ mean? Who examines the wounded brother of the dead German? In the trench, how does the soldier behave towards his prisoners? How does the soldier perceive these two ‘enemies?’ Give evidence to support your answer. How separate from them does he feel? What do the words ‘we who are set loose at each other’ suggest to you? Is the author implying something here? Why is the ‘happy face of the mother’ so poignant for the soldier? What could he be feeling as he imagines her? Discussion question: What does this episode tell us about the character of the soldier? Passages 5 & 6. pp. 124-126, 132-134. These passages show the reader the difference between the soldier’s understanding of the war, and that of English civilian population. Passage 5 begins: ‘I buy the tickets for the theatre’ and ends: with ‘Intermission.’ In the paragraph beginning: ‘On the stage a vulgar-faced comic is prancing up and down’, How does the author use language to portray the stage show in an unattractive light? On the following page, what does the author do to convey the meaningless emptiness of the performance? Is there anything missing from his description? What do you think the soldier is feeling when he looks around the theatre? Which feelings is he expressing when he says: ‘They have no business to forget. They should be made to remember.’ What does the soldier mean by these statements? In what sense is the soldier’s voice drowned out? When the soldier neglects to answer the civilian and simply stares at him, the civilian interprets his response as ‘shell-shocked.’ What is your response to the civilian? Does he know what shell-shock is? What do you think causes the soldier to hate his audience? Passage 6 begins: ‘Westminster Abbey’ and ends: ‘We part at a corner of the street.’ What does the Curate mean when he says: ‘itching to get back.’ Do you think the Curate understands the soldier’s reply? Is the soldier’s reply a joke? When the soldier interprets the Curate’s story of the men, leading their soldiers into machine gun fire armed only with a walking stick, as a newspaper story, why does the Curate reject this interpretation? Why do you think the soldier does not argue with the Curate about the ‘heroic qualities’ of the British soldier? Discussion question: How much of the soldier’s alienation from the civilian population is simply attributable to his exhausted condition? VATE Inside Stories -Teachng Notes Generals Die in Bed 20 Passage 7. pp. 207-208. Passage begins: ‘We are lying on our stretchers…’ and ends: ‘I am carried up the gangplank. In reality, what happened to the Llandovery Castle? Why was it sunk? When the soldier hears the truth, what does he do? What in fact had the General done to his men? Why is the first picture of the surrendering Germans slightly comic? What is the final picture of the Germans and how are meant to respond? Why do you think these two pictures, side by side as it were, end the book? Discussion: what evidence in the book is there for the claim that the Germans are not the real enemy of the soldier? VATE Inside Stories -Teachng Notes Generals Die in Bed 21 Section 7. Further activities for exploring the text Some students may wish to read All Quiet on the Western Front. Generals Die in Bed is a text full of poetic imagery. Use the table below to collect images under the following headings: Imagery of human suffering examples Imagery of Chaos examples Imagery of beauty examples Imagery of Death Examples Imagery of the effects of war examples Imagery of tenderness examples Imagery of violence examples Imagery of cruelty Examples VATE Inside Stories -Teachng Notes Generals Die in Bed 22 Themes in the text Some themes explored in the novel are listed below. Survival The machinery of war The treatment of the men by the army The destructiveness of war. For each theme, find the following: Incidents which develop the theme Key characters Quotes Connections with other themes Writing tasks Using the BBC history website www.bbc.co.uk/history/war/wwone/index/shtml, access some of the letters or diaries from the front. Students could be asked to write: the diary of the soldier, reflecting on his experience in the German trench a letter to Gladys, wondering if she remembers this particular ‘boy.’ a letter to Martha from Cleary to ease her pain and loss. a letter to Martha from Clark in his official capacity. Script an interview between the soldier and a colonel about his commendation. VATE Inside Stories -Teachng Notes Generals Die in Bed 23 Research topics Have students research the term ‘shell shock.’ Listen to songs of the First World War. Compare the verses in the songs with other poems of World War One. Students could be asked why the songs are apparently so jolly. Using the BBC website or that of the Imperial War Museum find newspaper reports of battles in World War One and compare them with poetry or extracts from the novel. What do the reports say about the public’s understanding of the war? Poetry of World War One Photocopy two poems, Suicide in the Trenches and The Happy Warrior from Men who march away (pp. 86-87). Students could be asked to describe the tone of both poems, to discuss the author’s purpose in writing, and his attitude to his readers. What do these two poems imply about the prevailing view of war in Britain and the Allies? Of what parts of the book do they remind the students? Although Generals Die in Bed was written at least ten years after most of the war poetry, it would be helpful to compare the four texts quoted in the War as Grandeur section of the introduction using the following questions as a guide: o How is the soldier portrayed in each text? o What do the Tolstoy text and Rupert Brooke’s Peace have in common? Similarities of imagery, tone, ideas? Why cleanness? o How is death portrayed in The Soldier, as something momentous or not? What images of England are in the poem? What values does England embody for the speaker in the poem? What might be the author’s intention in writing the poem? o What picture does the first half of the poem Dulce et decorum est give of war, and how does it compare with the picture of war in the other texts? o Comment on some of the vivid imagery in the first half of the poem. o How has the experience of the man suffering from the gas affected the poet? o Why do you think the poet uses the word, ‘children’ in the poem? o What might be the author’s intention in writing the poem? Teachers might like to discuss with students how Dulce et decorum est presents the poet, as an active participant, as someone who registers the horror of war, and holds these dreadful images before our eyes, so we will register their horror as well. Could Harrison’s soldier be compared with Owen? VATE Inside Stories -Teachng Notes Generals Die in Bed 24 Section 8. Key Quotes Chapter and Page number Quotation Moment in the novel Chapter 1. P. 17. ‘I remember the taunting song “Oh my, I’m too young Just before he arrives at the station. Chapter 2. P. 26. ‘A blinding flash and an exploding howl a few feet in front of the trench. My bowels liquefy.’ ‘To our right they have started to shell the front lines. It is about half a mile away. We do not care. We are safe’ ‘I can find nothing to appease my terror.’ ‘We have long since learned that the word ‘rest’ is another military term meaning something altogether different.’ ‘We are alive with vermin and sit picking at ourselves like baboons.’ ‘We have heard every physical and emotional foible of Martha’s. It seems as though we are all married to her.’ ‘This is war; there is so much misery, heartaches, agony, and nothing can be done about it.’ ‘Somewhere it is summer, but here are the same trenches. The trees here are skeletons holding stubs of stark, shellamputated arms. No flowers grow in this waste land.’ As the smudge of grey appears in the east, the odours of the trenches rise in a miasmal mist on all sides of us. A thousand thundering orders! A thousand trivial rules, each with a penalty for infraction, has made will-less robots of us all. The first bombardment. Chapter 2. P. 27. Chapter 2. P. 27-28. Chapter 3. P. 34. Chapter 3. P. 36. Chapter 3. P. 37 Chapter 3 P. 43. Chapter 4 P. 45-46. Chapter 4 P. 46. Chapter 4 P. 47. to die.” VATE Inside Stories -Teachng Notes The first bombardment. The first bombardment. While on rest for the first time. While on rest the first time. While on rest the first time. In the estaminet, while on rest the first time. All along the front. All along the front. While crawling trenches. Generals Die in Bed in the 25 Chapter 4 P. 53. Chapter 5 P. 59. Chapter 5 P. 60. Chapter 5 P. 69. Chapter 5 P. 71. Chapter 6 P. 73. Chapter 6 P. 75. Chapter 6 P. 77. Chapter 6 p. 81. Broadbent takes the bread and cheese out of brown’s haversack and shares it with us. “Anyway” he explains, “he can’t eat anymore…..” We are lying near a field of blossoming beans. The air is filled with the heavy fragrance. We take deep, long inhalations. Our bodies are cooling and the foul trench odours cease stirring, We speak respectfully of Brown now. He is dead. He is not the awkward stupid boy we knew. He is a symbol. Who can describe the few moments of peace and security in a soldier’s life? The animal pleasure in feeling the sun on a naked body. The cool, caressing, lapping water. The feeling of security, of deep, inward happiness. Our day is spoiled for us by this lonely dead soldier, carried to us from the front By the sparkling, sunlit water of the Somme. Out on rest we behaved like human beings; here we are merely soldiers. We know what soldiering means. It means saving your own skin and getting a bellyful as often as possible……..that and nothing else. There is no time for rest. We stagger around like drunken, forsaken men. Life has become an insane dream. The crashing of the shells comes closer and closer. Our ears are attuned to the nuances of a bombardment. Who can live through the terror-laden minutes of drumfire and not feel his reason slipping, his manhood dissolving? VATE Inside Stories -Teachng Notes Not long after Brown is shot by a sniper. After they have marching for hours. been While smelling the beans. The little river. The little river. Back in the line. Back in the line. Back in the line. Back in the line. Generals Die in Bed 26 Chapter 6 P. 81. Chapter 6 P. 82. Chapter 6 P. 92. Chapter 6 P. 95. Chapter 6 P. 98. Chapter 6 P. 103. Chapter 7 P. 112. Chapter 7 P. 113. Chapter 8 P. 125. Chapter 8 P. 133-134. Chapter 9 P. 143. Chapter 9 P. 148. Chapter 11 P. 174. Chapter 11 P. 184. Back at home they are praying, too - praying for victory – and that means that we must lie here and rot and tremble forever….. It’s beer we want. To hell with the glory. They are boys of about seventeen. Their uniforms are too big for them and their thin necks poke out of enormous collars. How can I say to this boy that something took us both, his brother and me, and dumped us into a lonely shrieking hole at night. I am proud of myself. I have been tested and found not wanting. It is better I say to myself, not to seek for answers. It is better to live like an unreasoning animal. God no. Generals die in bed. In the seams and crotches of the fresh underclothing we see lurking pale lice as large as rice grains. They have no business to forget. They should be made to remember. “But the best thing about the war to my way of thinking is that it has brought out the most heroic qualities in the common people, positively Noble qualities…” He goes on and on. We are to advance behind a sheet of seething flame. I am filled with a frenzied hatred for these men. There is not a single soul in sight other than he marching troops. An American battalion comes up. This is their first trip into the line. They talk loudly and light cigarettes. They call to each other as though no enemy lay in hiding a few hundred yards off. VATE Inside Stories -Teachng Notes Back in the line. Back in the line. During the attack, after the bayonet incident. The capture of the German prisoners. Having turned prisoners. Reflecting experiences. over the on his Soldiers talking parade. The quarterly bath. after At the theatre. Meeting the Anglican curate at the Abbey. Just before the attack. The counter-attack. Entering Arras. At the front after Arras. Generals Die in Bed 27 Chapter 12 P. 189. Chapter 12 P. 191. Chapter 12 p. 191. Chapter 12 P. 203. The food becomes poor. We are being hardened. ….an enemy like the German – no, I will not call him German – an enemy like the Hun does not merit humane treatment in war. “…….I’m not saying for you not to take prisoners. That’s against international rules. All that I’m saying is that if you take any we’ll have to feed them out of our rations…..” The pool of blood grows as though it were fed by a subterranean spring. It fills the narrow, conical bottom of the hole. VATE Inside Stories -Teachng Notes Before the last attack. Colonel addressing the troops about the Llandover Castle incident. Colonel addressing the troops about the Llandover Castle incident. Broadbent’s fatal wound. Generals Die in Bed 28 Section 9. Essay topics Part 1. 1. In Generals Die in Bed how well do the Canadian soldiers deal with the challenges of war? 2. 'In Generals Die in Bed, the young soldier’s imagination distinguishes him from the other characters': Discuss. 3. 'The soldier is the only character who is not defeated by war': Do you agree? 4. 'The soldier’s experience in war convinces him that the only enemies are the generals': Discuss. 5. 'In Generals Die in Bed’ the destructiveness of war overwhelms all who experience it': Do you agree? Part 2. 6. 'Generals Die in Bed presents the horrifying experience of war in the trenches of World War 1': Discuss. 7. 'Generals Die in Bed shows men struggling to remain human under the most degrading of conditions: Discuss. 8. 'Generals Die in Bed shows how war makes compassion irrelevant': Do you agree? 9. 'Generals Die in Bed shows how war alienates soldiers from each other and the civilian population': Discuss 10. 'Generals Die in Bed shows the immensity, the pointlessness, and the waste of modern organised warfare': Discuss. VATE Inside Stories -Teachng Notes Generals Die in Bed 29 Section 10. References and resources Texts Harrison, Charles Yale. Generals Die in Bed, Penguin 2002. Fussell, Paul. The Great War and modern memory, OUP 1977. Tolstoy, L.N. War and Peace, tr. R. Edmonds, Penguin 1982. (Video) Hemingway, Ernest. A Farewell to Arms, Penguin 1935. Graves, Robert. Goodbye to all that, Penguin 1960. Remarque, Erich Maria. All Quiet on the Western Front, Ballantine, 1982. (Video) Websites Book Cover: www.lib.byu.edu/~english/ww1/critical/html BBC History: www.bbc.co.uk/history/war/wwone/index/shtml Posters: www.library.georgetown.edu-dept-speccoll-amposter.htm VATE Inside Stories -Teachng Notes Generals Die in Bed 30