Abandonment

advertisement

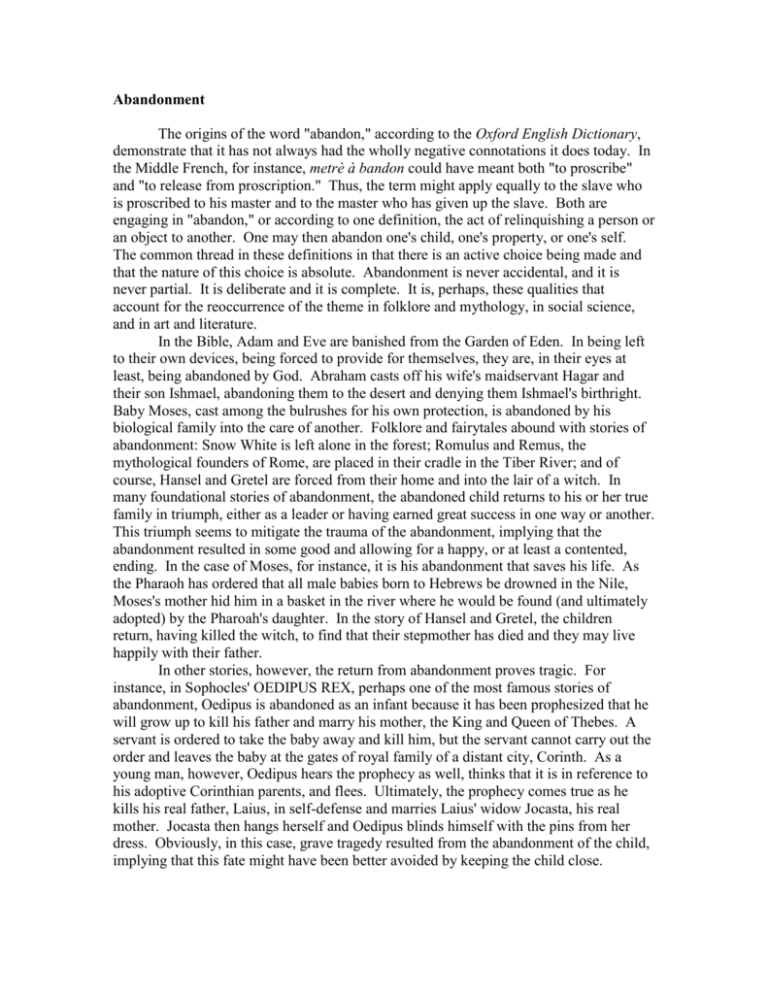

Abandonment The origins of the word "abandon," according to the Oxford English Dictionary, demonstrate that it has not always had the wholly negative connotations it does today. In the Middle French, for instance, metrè à bandon could have meant both "to proscribe" and "to release from proscription." Thus, the term might apply equally to the slave who is proscribed to his master and to the master who has given up the slave. Both are engaging in "abandon," or according to one definition, the act of relinquishing a person or an object to another. One may then abandon one's child, one's property, or one's self. The common thread in these definitions in that there is an active choice being made and that the nature of this choice is absolute. Abandonment is never accidental, and it is never partial. It is deliberate and it is complete. It is, perhaps, these qualities that account for the reoccurrence of the theme in folklore and mythology, in social science, and in art and literature. In the Bible, Adam and Eve are banished from the Garden of Eden. In being left to their own devices, being forced to provide for themselves, they are, in their eyes at least, being abandoned by God. Abraham casts off his wife's maidservant Hagar and their son Ishmael, abandoning them to the desert and denying them Ishmael's birthright. Baby Moses, cast among the bulrushes for his own protection, is abandoned by his biological family into the care of another. Folklore and fairytales abound with stories of abandonment: Snow White is left alone in the forest; Romulus and Remus, the mythological founders of Rome, are placed in their cradle in the Tiber River; and of course, Hansel and Gretel are forced from their home and into the lair of a witch. In many foundational stories of abandonment, the abandoned child returns to his or her true family in triumph, either as a leader or having earned great success in one way or another. This triumph seems to mitigate the trauma of the abandonment, implying that the abandonment resulted in some good and allowing for a happy, or at least a contented, ending. In the case of Moses, for instance, it is his abandonment that saves his life. As the Pharaoh has ordered that all male babies born to Hebrews be drowned in the Nile, Moses's mother hid him in a basket in the river where he would be found (and ultimately adopted) by the Pharoah's daughter. In the story of Hansel and Gretel, the children return, having killed the witch, to find that their stepmother has died and they may live happily with their father. In other stories, however, the return from abandonment proves tragic. For instance, in Sophocles' OEDIPUS REX, perhaps one of the most famous stories of abandonment, Oedipus is abandoned as an infant because it has been prophesized that he will grow up to kill his father and marry his mother, the King and Queen of Thebes. A servant is ordered to take the baby away and kill him, but the servant cannot carry out the order and leaves the baby at the gates of royal family of a distant city, Corinth. As a young man, however, Oedipus hears the prophecy as well, thinks that it is in reference to his adoptive Corinthian parents, and flees. Ultimately, the prophecy comes true as he kills his real father, Laius, in self-defense and marries Laius' widow Jocasta, his real mother. Jocasta then hangs herself and Oedipus blinds himself with the pins from her dress. Obviously, in this case, grave tragedy resulted from the abandonment of the child, implying that this fate might have been better avoided by keeping the child close. Perhaps abandonment appears so frequently in art and literature because, as some philosophers and psychologists believe, the fear of abandonment begins at birth. Sigmund Freud, the Austrian psychiatrist thought of as the father of modern psychological thought, believed that when we are born, and thus physically separated from our mothers, this trauma becomes a central force in our lives. We must, according to Freud, spend a great deal of our lives coming to terms with this separation, which we internalize as an abandonment (Freud pg. #). Later psychologists would delve deeper than Freud into the fear of and effect of abandonment upon our young psyches. In his highly influential three volume work Attachment, Separation, and Loss (1973), British psychologist John Bowlby discusses his decades long studies of children and their attachments to their caregivers, specifically their mothers. Bowlby notes that infants seek to find their mother when she leaves the room as soon as they are able to crawl. Additionally, the child will follow any familiar adult in lieu of the mother if she is unavailable (200-202). Infants demonstrate distress upon impending departure of the mother as soon as they are old enough to sense the signs that she is leaving, around six to nine months of age (204). For Bowlby, the infant is exhibiting the innate fear of abandonment, which produces anxiety. Psychologist Yi Fu Tuan calls fear of abandonment a "central childhood fear" and points to the frequent use of the motif in fairytales as a method of playing on that fear and keeping control of children (Salerno 98). If this abandonment does happen and it is prolonged, the anxiety becomes a part of the infant's, later the child's, later the adult's personality. He claims that adult anxiety disorders can be attributed to specific child-rearing practices; in particular, he says, frequent and regular separations, or even frequent and regular threats of abandonment bear huge consequences later in life (Salerno 97). Modern philosophers have also considered the fear of abandonment as a central component to modern consciousness. Soren Kierkegaard, 19th Century Danish philosopher, defines modern angst or anxiety as a feeling of looming danger where the source of the threat is unknown. G. W. F. Hegel, a German philosopher of the same era, claimed that the true mark of becoming human is not to desire, but to want to be the object of someone else's desire. Combining these theories then, and remembering as well Bowlby's infants, can lead to the theory that humans innately fear being abandoned and that as we grow older, we are consumed by a feeling that we will lose our most prized object: another human being. In other words, we live as adults with a constant fear of being abandoned, and if we were indeed abandoned as children, either actually or metaphorically, this fear can be the source of debilitating anxiety. 20th-century philosophers have taken these ideas and demonstrated how the detached, impersonal modern world exacerbates the natural fear of abandonment. The Industrial Revolution, the nineteenth-century shift from rural, manual labor to automated, technologically advanced work in the Western world, took control of the future out of the hands of the family and placed it in the hands of a stranger. Philosophers such as Theodor Adorno have theorized that this led to the breakdown of the family, as the father-figure, who perhaps felt abandoned himself, abandoned his own family in search of strong, authoritarian figures outside the family. French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, the primary figure in the school of philosophical thought known as Existentialism, rejected the very idea that the world is ordered and that human beings can make sense of it. Thus, he argued, we realize that we are alone, abandoned in the world. In literature, we see this crises of abandonment in the works of many different writers. In Mary Shelley's FRAKENSTEIN, for instance, Victor Frankenstein, the doctor who creates the famous monster, wants only to intellectualize, to think, never to emote or to feel. He leaves his loved ones lonely and alone in search of individual, intellectual glory. The monster he creates is in turned abandoned by Victor and spends the rest of the novel in search of a connection, resulting in tragic consequences. In Louise Erdrich's LOVE MEDICINE, abandonment is explored on an individual level, as there are several characters who are left alone and helpless, but also on a community level, as the Indian tribes of North American were abandoned by the U.S. Government that had promised to protect and provide for them. This novel demonstrates well why the theme of abandonment is so common in literature. On a personal level, all human beings feel a fear of abandonment stemming from our childhood separations from our parents. Additionally, however, in the modern world, whole communities might live in a general state of abandonment based on the impersonal, disconnected nature of modernity. See Also: CEREMONY, THE GOD OF SMALL THINGS, HUMBOLT'S GIFT, I KNOW WHY THE CAGED BIRD SINGS, THE JOY LUCK CLUB, MEMBER OF THE WEDDING, WHITE TEETH Bibliography: Bowlby, John. Attachment and Loss. New York: Basic Books, 1973. Salerno, Roger A. Landscapes of Abandonment: Capitalism, Modernity, and Estrangement. Albany: SUNY Press, 2003. Jennifer McClinton-Temple