WORD - Gravener

advertisement

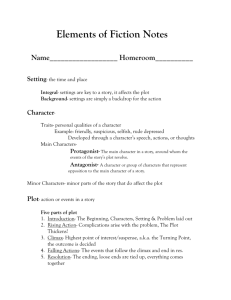

The Formal Elements of Fiction In the same way that a painter uses shape, color, perspective, and other aspects of visual art to create a painting, a fiction writer uses character, setting, plot, point of view, theme, and various kinds of symbolism and language to create artistic effect in fiction. These aspects of fiction are known as the formal elements. An understanding of the formal elements will enhance the reader’s appreciation of any piece of fiction, as well as his or her ability to share perceptions with others. For example, the concept of setting helps a reader of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “Young Goodman Brown” to recognize and discuss the significance of the “deep dusk of the forest” and the “uncertain light” encountered by Brown as he begins his dreamlike encounter with the devil. While the list of formal elements encourages us to divide a story into parts, in the story itself these elements blend to create a whole. At some level, or perhaps in the first reading of a piece, readers should read without applying these divisions in order to experience the story's unique effect. Nevertheless, knowledge of the formal elements is necessary for most critical discussions of fiction. These elements provide a basic vocabulary and set of critical tools that can be used in conjunction with many other critical approaches. DEFINITION OF PLOT Plot refers to the series of events that give a story its meaning and effect. In most stories, these events arise out of conflict experienced by the main character. The conflict may come from something external, like a dragon or an overbearing mother, or it may stem from an internal issue, such as jealousy, loss of identity, or overconfidence. As the character makes choices and tries to resolve the problem, the story's action is shaped and plot is generated. In some stories, the author structures the entire plot chronologically, with the first event followed by the second, third, and so on, like beads on a string. However, many other stories are told with flashback techniques in which plot events from earlier times interrupt the story's "current" events. All stories are unique, and in one sense there are as many plots as there are stories. In one general view of plot, however—and one that describes many works of fiction—the story begins with rising action as the character experiences conflict through a series of plot complications that entangle him or her more deeply in the problem. This conflict reaches a climax, after which the conflict is resolved, and the falling action leads quickly to the story's end. Things have generally changed at the end of a story, either in the character or the situation; drama subsides, and a new status quo is achieved. It is often instructive to apply this three-part structure even to stories that don't seem to fit the pattern neatly. conflict: The basic tension, predicament, or challenge that propels a story's plot complications: Plot events that plunge the protagonist further into conflict rising action: The part of a plot in which the drama intensifies, rising toward the climax climax: The plot's most dramatic and revealing moment, usually the turning point of the story 1 falling action: The part of the plot after the climax, when the drama subsides and the conflict is resolved PLOT EXERCISE Most plots develop because a character is in a situation involving conflict. The conflict might be a personal dilemma, a pressing desire, a threatening enemy, a burdensome duty, or the loss of something important. In most stories, a series of character choices leads ultimately to a resolution of the problem. Often the resolution comes about because the external situation is different (what was desired is acquired, the dragon is slain, and so on). Just as often, and especially in contemporary stories, something has changed internally in the character after the story’s resolution. He or she has gained an insight, adopted a new philosophy, or come to terms with a negative emotion. Instructions: For this exercise, select one character and one situation from each table. For example, your match might be this: “A recently divorced mother of three who suddenly needs to go to Ireland.” Choose one character: Choose one situation: thirty-year-old female airplane mechanic working college student taking too many credits retired architect living in Mexico an artist about to have his or her first gallery exhibit recently divorced mother of three aging hippie selling flowers at a busy intersection mayor of a small suburb twenty-year-old professional skateboarder learns about having a terminal illness wins the lottery suddenly wants to catch a fish for the first time begins to experience religious doubt needs to go to Ireland encounters an old enemy encounters an old romantic acquaintance is visited by three different annoying relatives at once Think of a basic plot outline using the character and situation you have selected. Based on this situation, what would happen first? What next? If possible, indicate what kind of climax or resolution might occur in this plot. Describe and discuss this basic plot outline, indicating why it is appropriate for the character and situation selected. 2 DEFINITION OF CHARACTER In fiction, character refers to a textual representation of a human being (or occasionally another creature). Most fiction writers agree that character development is the key element in a story's creation, and in most pieces of fiction a close identification with the characters is crucial to understanding the story. The story's protagonist is the central agent in generating its plot, and this individual can embody the story's theme. Characters can be either round or flat, depending on their level of development and the extent to which they change. Mrs. Mallard, in Kate Chopin’s “The Story of an Hour,” though developed in relatively few words, is a round character because she shows complex feelings toward her husband, and her character develops when she envisions the freedom of being widowed. Authors achieve characterization with a variety of techniques: by using the narrative voice to describe the character, by showing the actions of the character and of those reacting to her, by revealing the thoughts or dialogue of the character, or by showing the thoughts and dialogue of others in relation to the character. protagonist: A story’s main character (see also antagonist) antagonist: The character or force in conflict with the protagonist round character: A complex, fully developed character, often prone to change flat character: A one-dimensional character, typically not central to the story characterization: The process by which an author presents and develops a fictional character CHARACTER EXERCISE When a character is created in fiction, the various details provided by the author combine to create a believable representation of a person. Flat characters are typically developed in rough outline only, with such basic attributes as gender, age, and occupation or family role indicated but not much else. On the other hand, round characters are developed more fully. For instance, we may learn about their clothing preferences, skills, hopes or fears, favorite work of art or song, and relationships. Through narrative background, dialogue, transcriptions of characters’ thoughts, and characters’ actions, the author hopes to convey, in a round character, a believable “living” person. Instructions: Select one character trait from each of the columns below to create a basic character outline. A. B. fifteen years old male construction worker twenty years old twenty-five years old female pilot head of household thirty-five years old fifty years old seventy years old C. D. loner, estranged from family artist snowboarder computer programmer president of a large corporation 3 gentle, respectful, nurturing thoughtful, quiet attentive, intelligent, detached caustic, mean, scornful of others self-absorbed, vain Based on the character you've created, imagine and describe a potential conflict or story situation in which this character might be found. Explain how this character might resolve the conflict. Make your character more round by adding four or five additional details that seem to fit with this character. Select details that will coalesce with the conflict/situation expressed in the preceding question. Consider such aspects as personal habits, fears, desires, significant experiences, worst and best memories, relationships, strengths, weaknesses, and finances. Go back to the columns and change one basic aspect. Would the new character still fit in the same situation suggested for the second question? Would he or she still fit the details expressed in this question? Explain why or why not, based on character traits. DEFINITION OF SETTING Setting, quite simply, is the story’s time and place. While setting includes simple attributes such as climate or wall décor, it can also include complex dimensions such as the historical moment the story occupies or its social context. Because particular places and times have their own personality or emotional essence (such as the stark feel of a desert or the grim, wary resolve in the United States after the September 11th attacks), setting is also one of the primary ways that a fiction writer establishes mood. Typically, short stories occur in limited locations and time frames, such as the two rooms involved in Kate Chopin’s "The Story of an Hour," whereas novels may involve many different settings in widely varying landscapes. Even in short stories, however, readers should become sensitive to subtle shifts in setting. For example, when the grieving Mrs. Mallard retires alone to her room, with "new spring life" visible out the window, this detail about the setting helps reveal a turn in the plot. Setting is often developed with narrative description, but it may also be shown with action, dialogue, or a character’s thoughts. social context: The significant cultural issues affecting a story’s setting or authorship mood: The underlying feeling or atmosphere produced by a story SETTING EXERCISE Characters in a story all have to interact in one way or another with its setting. Setting can often help reveal character traits, and it is one of the primary ways an author establishes the story’s mood. In some stories, the setting can strongly affect the plot, functioning almost like another character. An example of this is Jack London’s “To Build a Fire,” in which the frozen Yukon functions as an antagonist. More commonly, though, the setting is always there as a foundation for the story—illuminating character aspects, influencing actions, and helping to set the mood. Instructions: For this exercise, select one place and one descriptive detail of setting from each column. A. A sports stadium A desert valley A city street A hotel suite A used car lot An emergency room A train B. On Halloween During a heat wave After the U.S. has miraculously won the World Cup in soccer After the September 11th attacks In the year 2050 During a power outage On the day of a wedding 4 Using the selected combination as a starting point, write a brief description of this setting, including additional details to help develop it. What mood is created by the setting you described? Explain how the setting's details help to establish its mood. DEFINITION OF POINT OF VIEW Point of view in fiction refers to the source and scope of the narrative voice. In the first-person point of view, usually identifiable by the use of the pronoun "I," a character in the story does the narration. A first-person narrator may be a major character and is often its protagonist. For example, the point of view in Jamaica Kincaid's "Girl" becomes evident when the protagonist responds, "I don't sing benna at all on Sundays, and never in Sunday school." A first-person narrator may also be a minor character, someone within the story but not centrally involved, as in William Faulkner's "A Rose for Emily," which is told by a member of the town who is not active in the plot but has observed the events. The author's choice of point of view has a significant effect on the story's voice and on the type of information given to the reader. In first-person narration, for example, what can be shown is limited to the character's observation and thoughts, and any skewed perceptions in the narrator will be passed on to the reader. Third-person point of view occurs when the narrator does not take part in the story. "I don't sing benna at all on Sundays" might become, in the third person, "She never sings benna on Sundays." There are three types of third-person point of view. In third-person omniscient, the narrative voice can render information from anywhere, including the thoughts and feelings of any of the characters. This all-knowing perspective allows the narrator to roam freely in the story's setting and even beyond. In third-person limited, sometimes called third-person sympathetic, the narrative voice can relate what is in the minds of only a select few characters (often only one, the point-of-view character). In third-person objective, the narrator renders explicit, observable details and does not have access to the internal thoughts of characters or background information about the setting or situation. A character's thoughts, for example, are inferred only by what is expressed openly, in actions or in words. This point of view is also known as third-person dramatic because it is generally the way drama is developed. While the second-person point of view exists, it is not used very often because making the reader part of the story can be awkward: "You walk to the end of the road and pause before heading towards the river." narrative voice: The voice of the narrator telling the story point-of-view character: The character focused on most closely by the narrator; in first-person point of view, the narrator himself POINT OF VIEW EXERCISE Instructions: Consider the following versions of part of a well-known fairy tale. Compare and contrast the two versions and answer the question that follows. Next, read the next fairy tale and write your own version of the tale in first-person, from the point of view of any of the characters. How does your version change your understanding of the characters? 5 Third-person omniscient: Goldilocks was a proud and defiant little girl who’d been told many times by her mother to stay out of the woods, but she paid little attention to others, especially her elders, giving lots of attention instead to herself and her own desires. One day, just to show that she could, she wandered deep into the center of the forest, farther from home than ever before. In a clearing she noticed a small cottage, smoke issuing from the chimney. She thought it was quite an ugly little cottage, but she also thought it might be a place where she could get a little something to eat and drink. The front door swung open when she touched it. “Hello,” she said. “Is anyone home?“ No one answered, but she stepped inside anyway. Immediately the smell of fresh-cooked porridge drew her toward the kitchen, where she saw three steaming bowls sitting on the counter. First person: Make your bed, she says. Read your lessons. Fold your clothes. Stay out of the woods. Blah blah blah. Ha! I'm in the woods now, dear mother, and going deeper. As if anything out here would dare to harm a girl like me. I've followed the weaving trail through the trees farther than ever before, and what can she do about it? I'm deep in the woods now, and there's a cottage in a clearing, a muddy-looking wooden thing so small I almost miss it. What a hovel! Who could stand to live there? I want to get inside and see. Besides, I'm thirsty, and a little bit hungry after the long walk, and these country folk do so love to share. They don't use locks out here, of course, and as soon as I touch the door it swings wide open for me. I say hello, but no one answers. Even if they catch me here, who would care? A proper little girl like me can't harm a thing. I step inside. They must have known I was coming, because someone’s made a tasty-smelling porridge. When I see the brown bowls steaming on the plain wooden counter, I feel so hungry I could eat all three. Compare and contrast these two perspectives in terms of their style, content, character development, and overall effect on the reader. Why do you think most traditional fairy tales are expressed in the third person? Little Red-Cap Once upon a time there was a dear little girl who was loved by every one who looked at her, but most of all by her grandmother, and there was nothing that she would not have given to the child. Once she gave her a little cap of red velvet, which suited her so well that she would never wear anything else; so she was always called "Little Red-Cap." One day her mother said to her, "Come, Little Red-Cap, here is a piece of cake and a bottle of wine; take them to your grandmother, she is ill and weak, and they will do her good. Set out before it gets hot, and when you are going, walk nicely and quietly and do not run off the path, or you may fall and break the bottle, and then your grandmother will get nothing; and when you go into her room, don't forget to say, 'Good-morning,' and don't peep into every corner before you do it." "I will take great care," said Little Red-Cap to her mother, and gave her hand on it. The grandmother lived out in the wood, half a league from the village, and just as Little Red-Cap entered the wood, a wolf met her. Red-Cap did not know what a wicked creature he was, and was not at all afraid of him. "Good-day, Little Red-Cap," said he. "Thank you kindly, wolf." "Whither away so early, Little Red-Cap?" "To my grandmother's." "What have you got in your apron?" "Cake and wine; yesterday was baking-day, so poor sick grandmother is to have something good, to make her stronger." "Where does your grandmother live, Little Red-Cap?" "A good quarter of a league farther on in the wood; her house stands under the three large oak-trees, the nut-trees are just below; you surely must know it," replied Little Red-Cap. 6 The wolf thought to himself, "What a tender young creature! what a nice plump mouthful -- she will be better to eat than the old woman. I must act craftily, so as to catch both." So he walked for a short time by the side of Little Red-Cap, and then he said, "See Little Red-Cap, how pretty the flowers are about here -- why do you not look round? I believe, too, that you do not hear how sweetly the little birds are singing; you walk gravely along as if you were going to school, while everything else out here in the wood is merry." Little Red-Cap raised her eyes, and when she saw the sunbeams dancing here and there through the trees, and pretty flowers growing everywhere, she thought, "Suppose I take grandmother a fresh nosegay; that would please her too. It is so early in the day that I shall still get there in good time;" and so she ran from the path into the wood to look for flowers. And whenever she had picked one, she fancied that she saw a still prettier one farther on, and ran after it, and so got deeper and deeper into the wood. Meanwhile the wolf ran straight to the grandmother's house and knocked at the door. "Who is there?" "Little Red-Cap," replied the wolf. "She is bringing cake and wine; open the door." "Lift the latch," called out the grandmother, "I am too weak, and cannot get up." The wolf lifted the latch, the door flew open, and without saying a word he went straight to the grandmother's bed, and devoured her. Then he put on her clothes, dressed himself in her cap, laid himself in bed and drew the curtains. Little Red-Cap, however, had been running about picking flowers, and when she had gathered so many that she could carry no more, she remembered her grandmother, and set out on the way to her. She was surprised to find the cottage-door standing open, and when she went into the room, she had such a strange feeling that she said to herself, "Oh dear! how uneasy I feel to-day, and at other times I like being with grandmother so much." She called out, "Good morning," but received no answer; so she went to the bed and drew back the curtains. There lay her grandmother with her cap pulled far over her face, and looking very strange. "Oh! grandmother," she said, "what big ears you have!" "The better to hear you with, my child," was the reply. "But, grandmother, what big eyes you have!" she said. "The better to see you with, my dear." "But, grandmother, what large hands you have!" "The better to hug you with." "Oh! but, grandmother, what a terrible big mouth you have!" "The better to eat you with!" And scarcely had the wolf said this, than with one bound he was out of bed and swallowed up Red-Cap. When the wolf had appeased his appetite, he lay down again in the bed, fell asleep and began to snore very loud. The huntsman was just passing the house, and thought to himself, "How the old woman is snoring! I must just see if she wants anything." So he went into the room, and when he came to the bed, he saw that the wolf was lying in it. "Do I find thee here, thou old sinner!" said he. "I have long sought thee!" Then just as he was going to fire at him, it occurred to him that the wolf might have devoured the grandmother, and that she might still be saved, so he did not fire, but took a pair of scissors, and began to cut open the stomach of the sleeping wolf. When he had made two snips, he saw the little Red-Cap shining, and then he made two snips more, and the little girl sprang out, crying, "Ah, how frightened I have been! How dark it was inside the wolf;" and after that the aged grandmother came out alive also, but scarcely able to breathe. Red-Cap, however, quickly fetched great stones with which they filled the wolf's body, and when he awoke, he wanted to run away, but the stones were so heavy that he fell down at once, and fell dead. Then all three were delighted. The huntsman drew off the wolf's skin and went home with it; the grandmother ate the cake and drank the wine which Red-Cap had brought, and revived, but Red-Cap thought to herself, "As long as I live, I will never by myself leave the path, to run into the wood, when my mother has forbidden me to do so." DEFINITION OF STYLE, TONE, AND LANGUAGE Style in fiction refers to the language conventions used to construct the story. A fiction writer can manipulate diction, sentence structure, phrasing, dialogue, and other aspects of language to create style. Thus a story's style could be described as richly detailed, flowing, and barely controlled, as in the case of Jamaica Kincaid's "Girl," or sparing and minimalist, as in the early 7 work of Raymond Carver, to reflect the simple sentence structures and low range of vocabulary. Predominant styles change through time; therefore the time period in which fiction was written often influences its style. For example, Nathaniel Hawthorne's "Young Goodman Brown," written in the nineteenth century, uses diction and sentence structure that might seem somewhat crisp and formal to contemporary readers: "With this excellent resolve for the future, Goodman Brown felt himself justified in making more haste on his present evil purpose." The communicative effect created by the author's style can be referred to as the story's voice. To identify a story's voice, ask yourself, "What kind of person does the narrator sound like?" A story's voice may be serious and straightforward, rambunctiously comic, or dramatically tense. In "Girl," the voice of the mother, as narrated to us in the daughter's first-person point of view, is harsh and judgmental, exposing an urgent and weathered concern for the daughter's development as she becomes a woman. A story's style and voice contribute to its tone. Tone refers to the attitude that the story creates toward its subject matter. For example, a story may convey an earnest and sincere tone toward its characters and events, signaling to the reader that the material is to be taken in a serious, dramatic way. On the other hand, an attitude of humor or sarcasm may be created through subtle language and content manipulation. In the last line of Chopin's "The Story of an Hour," for example, an ironic spin emerges when we learn that "the doctors said she died of heart disease, of joy that kills." diction: The author's choice of words STYLE, TONE, AND LANGUAGE EXERCISE The English language offers a vast array of choices in sentence structure, phrasing, vocabulary, verb tense, and voice. Fiction writers use this variety to their advantage in crafting a thought, description, or action. Different language choices can create a huge range of styles and tones for any given expression. These different styles and tones give the story its unique meaning. In most cases, a story’s way of being told is at least as significant as its content. Let’s take, for example, the somewhat common experience of getting a parking ticket. Here are several ways the parking ticket experience might be expressed by the recipient. The policeman gave me a parking ticket. Some bored cop tagged me with another ticket. Someone had slipped the ticket under my windshield wiper like a blade slipped under a rib. A citation for violation of parking regulations had been affixed to my car. I got another &*%@# ticket! Another week goes by, another parking ticket stuck to the car—what else is new? 8 These various expressions create different emotional and conceptual stances relative to the ticketing experience. In other words, the language style of each expression adds its unique spin to the basic information. Instructions: For the following expression, use the columns below to substitute each numbered word or phrase to alter the wording and create a new, unique expression. The myriad (1) forms (2) of discourse (3) encountered (4) in contemporary society (5) require a matrix (6) of relational strategies (7). 1. many several varied 2. types kinds manifestations 3. communication speaking styles speech 6. mix variety large repertoire 7. methods of interaction communication techniques speaking styles 4. found evident that exist 5. modern life society today's world Experiment with the choices until you create an expression that seems stylistically different from the original. Compare and contrast the styles of the original sentence and your altered version by analyzing how the specific wording affects the styles. DEFINITION OF THEME Theme is the meaning or concept we are left with after reading a piece of fiction. Theme is an answer to the question, "What did you learn from this?" In some cases a story's theme is a prominent element and somewhat unmistakable. It would be difficult to read Kate Chopin's "The Story of an Hour" without understanding that the institution of nineteenth-century marriage robbed Mrs. Mallard of her freedom and identity. In some pieces of fiction, however, the theme is more elusive. What thought do we come away with after reading Jamaica Kincaid's "Girl"? That mothers can try too hard? That oppression leads to oppression? That a parent's repeated dire predictions have a way of becoming truth? Too much focus on pinning down a story's theme can obscure the accompanying emotional context or the story's intentional ambiguity (especially for contemporary fiction). In most cases, though, theme is still an important element of story construction (even in its absence), providing the basis for many valuable discussions. 9 THEME EXERCISE The Hare and the Tortoise One day the speedy hare was bragging among his fellow animals. “I have never been beaten in a race,” he said. “When I use my amazing speed, the race is over almost instantly. Would any of you like to take me on?” “I’ll challenge you,” said the tortoise. “You against me?” said the hare, laughing. He turned to the other animals. “Hurry. Set us up a course. This will be quick work for me. I’ll teach this plodder a lesson in speed.” The animals set up a course, and the race began. The fast hare sped so far ahead that he looked back and couldn’t even see the tortoise. To show his contempt, he decided to lie down and rest, and he soon fell asleep. Meanwhile, the tortoise kept going at a slow, steady pace. He finally crawled past the sleeping hare, and took the lead. In fact, the tortoise was just inches short of the finish line when the hare woke up and saw what had happened. The stunned hare sped to the finish line, but he couldn’t catch up, and the tortoise won. “Slow and steady wins the race,” said the smiling tortoise. In this well-known fable of Aesop, the final lesson emanating from the smiling tortoise is somewhat evident. This “moral to the story” is a good way to begin understanding the concept of theme. Although the theme in a short story or novel is almost never stated this explicitly, most works of fiction do teach us lessons. A story is typically a series of events in which a character resolves an important problem or conflict, often in a life-changing way, and typically such breakthroughs can reveal important guidelines about life. We might learn, for example, that it is important to take risks, or that wealth doesn’t bring happiness, or that a little bit of hope and persistence can change a bad situation. Not all events teach lessons, but the ones that do often make good stories. Instructions: Now read this modification of Aesop’s fable written by American writer Ambrose Bierce (1862–1914). The Hare and the Tortoise A Hare, having ridiculed the slow movements of a Tortoise, was challenged by the latter to run a race, a Fox to go to the goal and be the judge. They got off well together, the Hare at the top of her speed, the Tortoise, who had no other intention than making his antagonist exert herself, going very leisurely. After sauntering along for some time he discovered the Hare by the wayside, apparently asleep, and seeing a chance to win pushed on as fast as he could, arriving at the goal hours afterward, suffering from extreme fatigue and claiming the victory. “Not so,” said the Fox; “the Hare was here long ago, and went back to cheer you on your way.” 10 What theme does this modified version of the fable provide? How does it differ from the theme of the original? Is the theme as explicit and clear as it is in the original version of the tale? Why or why not? DEFINITION OF SYMBOLISM, ALLEGORY, AND IMAGE An image is a sensory impression used to create meaning in a story. For example, near the beginning of "Young Goodman Brown," we see Faith, Brown's wife, "thrust her own pretty head into the street, letting the wind play with the pink ribbons of her cap." While visual imagery such as this is typically the most prominent in a story, good fiction also includes imagery based on the other senses: sound, smell, touch, and taste. If an image in a story is used repeatedly and begins to carry multiple layers of meaning, it may be significant enough to call a symbol. Symbols are often objects, like a toy windmill or a rose, or they may be parts of a landscape, like a river. While a normal image is generally used once, to complete a scene or passage, a symbol is often referred to repeatedly and carries meanings essential to the story. Some symbols are universal, like water for cleansing, but others are more culturally based. In some African societies, for example, a black cat is seen as good luck. Fiction writers use preexisting cultural associations as well as meanings drawn from the context of the story to create multiple levels of meaning. Faith's pink ribbons in "Young Goodman Brown" carry cultural connotations of innocence and purity, but the fact that the wind plays with the ribbons in one key image also brings to mind temptation, alluring chaos, the struggle with natural forces. Red is also a significant color in the story's final temptation scene, with its basin of "water, reddened by the lurid light? Or was it blood?" Faith's pink ribbons carry, of course, a tinge of red. An allegory is a work of fiction in which the symbols, characters, and events come to represent, in a somewhat point-by-point fashion, a different metaphysical, political, or social situation. In Western culture, allegories have often been used for instructive purposes around Christian themes. For example, in John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress, a protagonist named Christian goes on a journey in which he encounters complicating characters and situations such as Mr. Worldly Wiseman, Vanity Fair, and the Slough of Despair, thus depicting the struggles of a Christian trying to stay pure. In some ways Nathaniel Hawthorne's "Young Goodman Brown" is structured as an allegory, as is evident in the character Faith, the Devil offering his snakelike staff, the temptation scene, and so on. Hawthorne skillfully manipulates the conventions of allegory, however, to resist a fixed meaning and create an ending that is open to interpretation. visual imagery: Imagery of sight aural imagery: Imagery of sound (e.g., the soft hiss of skis) olfactory imagery: Imagery of smell (e.g., the smell of spilled beer) tactile imagery: Imagery of touch (e.g., bare feet on a hot sidewalk) gustatory imagery: Imagery of taste (e.g., the bland taste of starchy bananas) 11 SYMBOLISM, ALLEGORY, AND IMAGE EXERCISE William Faulkner spoke of the “eternal verities,” lasting principles found consistently in human experience, such as love, hope, hate, fear, and compassion. Through the ages, these fundamental aspects of humanity have drawn the attention of writers and other artists. Such principles are often rendered symbolically because they are important yet abstract. Hope cannot be touched or quantified, but a toy windmill symbolizing hope can be experienced tangibly. Symbolism offers a way for writers to capture these important intangibles that inform and shape our lives. Instructions: From the boxes below, select one of the abstract terms. Then think of at least three symbols that a writer might use to capture the principle in a story. Write the symbols in the box. Love Treachery Hope Compassion Regret Hate Faith Desire Symbols often carry multiple meanings in a story. For example, a simple lamp, if worked into the story’s setting and plot appropriately, might signify knowledge, personal warmth, and hope all at once. The lamp might also function literally as a lamp—perhaps as something bought at a yard sale. This multiple layering of meaning is what gives many symbols their artistic power. Select one item from the boxes below and indicate at least three different meanings or functions that it might carry in a story. A pair of worn shoes A hotrod A kite A tube of red lipstick A pet rabbit A fountain 12 A piano A rose