For the Microsoft Word version of this case study

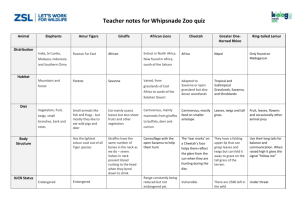

advertisement

Managing Savanna Ecosystems Savanna ecosystems cover about one-quarter of the world’s land surface and are found between the tropical rainforests and the subtropical, high-pressure belts that produce the world’s great deserts. The savanna regions have developed owing to a variety of factors, including climate, soils, geomorphology, fire and the overgrazing of animal herds. Savanna ecosystems in Swaziland in Southern Africa, like savannas elsewhere, depend on an inter-relationship between plants, animals and the physical environment. These areas are under increasing pressure from human activities and protecting them remains a concern and a challenge. Features of the African savanna Savanna grasslands develop where temperatures are high, precipitation is low and a seasonal drought is common. However, unreliable rainfall or water shortages are not the only reasons for the formation of a savanna. Other factors play a key role in the formation and maintenance of these ecosystems. Location Savanna grasslands occur in a broad band about 5–15° north and south of the equator, between the tropical rainforests and the hot deserts of the subtropics. Savannas occupy 65 per cent of Africa’s land area. Figure 1. Animals grazing by the water in Swaziland. Climate The savanna is characterised by a subtropical wet-dry climate. The wet season occurs in summer when heavy convectional (monsoonal) rain replenishes the parched vegetation and soil. Although rainfall can vary from as little as 500 mm to as much as 2,000 mm (enough to support a deciduous forest), all savanna areas have an annual drought, which can last from one to eight months. These droughts allow grasses to flourish. Temperatures remain high throughout the year, ranging between 23 °C and 28 °C. The hot temperatures, creating high evapotranspiration rates, and the seasonal nature of the rainfall cause a twofold division of the year into periods of water surplus and periods of water deficiency. This seasonal variation has a great effect on soil development. Soils Savanna soils are closely linked with climate and tend to reflect the local seasonal rainfall pattern. Soils in the savanna are commonly leached, ferralitic soils. These are similar to soils of the rainforest, but not as intensely weathered. Soil development shows a marked seasonal pattern. During the wet season, the excess of precipitation (P) over potential evapotranspiration (E) means that leaching of soluble minerals and small particles will take place down through the soil. These nutrients are deposited deep within the soil. By contrast, in the dry season E is less than P, and so silica and iron compounds are carried up through the soil and precipitated close to the surface. Geomorphology plays an important role in affecting soil type. Some areas, notably the base of slopes and river valleys, are enriched by clay, minerals and humus deposited there. However, plateaus, plains and the tops of slopes may be depleted of nutrients by erosion. The local variations in soil create different types of vegetation: this is known as edaphic control. For example, thick, clay-based soils frequently produce woodland, whereas on leached, sandy soils with poor water retention, grassland predominates. Savanna areas are frequently found on tectonically stable geological shields, which have been weathered and are lacking in nutrients. Hence, even their river valleys may not be as fertile as their temperate counterparts. Vegetation There are many types of vegetation in savannas, including grasses, trees and scrub. All, however, are xerophytic (adapted to drought) and pyrophytic (adapted to fire). Adaptations to drought include deep taproots to reach the water table, partial or total loss of leaves, and sunken stomata on the leaves to reduce moisture loss. Adaptations to fire include very thick barks and thick budding that can resist burning, with the bulk of the biomass being below ground level to aid rapid regeneration after a fire. The growth tissue in grasses is located at the base of the shoot, close to the soil surface. This is the opposite of shrubs where growth occurs from the tips. This means that burning, and even grazing, grass encourages growth. The warm, wet summers allow much photosynthesis and there is a large net primary productivity of 900 g/m2 per year. This varies from about 1,500 g/m2 per year where the region borders the rainforest, to only about 200 g/m 2 per year where the area becomes savanna scrub. In contrast, the biomass varies considerably (depending on whether it is largely grass or wood) with an average of 4,000 g/m 2. Typical species in Africa include the acacia, palm and baobab trees and elephant grass, which can grow to a height of over 5 m. Trees grow to a height of about 12 m and are characterised by flattened crowns and strong roots (Figure 2). Figure 2. Vegetation adaptations within a savanna grassland. The nutrient cycle also illustrates the relationship between climate, soils and vegetation. The store of nutrients in the biomass is less than that in the rainforest because of the shorter growing season. Similarly, the store in the litter is small because of fire. Many of the nutrients are stored in the soil so that they are not burnt and leached out of the system. The role of fire, whether natural or man-made, is important as it helps to maintain the savanna as a grass community (Figure 3). It mineralises the litter layer, kills off weeds, competitors and diseases, and prevents trees from colonising relatively wet areas. Figure 3. Fire in a savanna ecosystem. Animals The African savanna has the largest variety of herbivores, with more than 40 types of grazers, including giraffes, zebras (Figure 4), gazelles, elephants and wildebeests. Selective grazing allows for a categorisation depending on the height at which they eat. For example, the giraffe feeds from the top of the tree, the rhinoceros eats the lower twigs and the gazelle survives on the grass beneath the trees. These animals, as well as birds, will migrate to search for water and fresh pastures during the dry season. Carnivores, including lions, cheetahs and hyenas, are also supported in the savanna. Other fauna creatures include locusts, which can decimate large areas of grassland with devastating speed, and termites, which aerate the soil and break down up to 30 kg of cellulose per hectare each year. In some areas up to 600 termite hills per hectare can be found, which has a significant effect on the upper horizons of the soil. Figure 4. Zebras in the Swaziland. The Swaziland savanna ecosystem The savanna ecosystem is the most extensive in Southern Africa (comprising 34 per cent of the land area). There are four ecosystems recognised in Swaziland: Montane grasslands Savanna-woodland mosaic Forests Aquatic systems (including rivers, streams, wetlands, marshes) The woodland and grassland ecosystems cover 48 per cent and 46 per cent of Swaziland, respectively, while the forest and aquatic ecosystems cover the remaining 6 per cent. The specific type of savanna vegetation present at a site depends on geography, soils, and the impact of herbivores, humans and fire. Geographically, Swaziland can be divided into four main regions (Figure 5): The Highveld: This covers about 29 per cent of the country. It is a mountainous landscape that is essentially part of the Drakensberg Escarpment. The Middleveld: This undulating landscape covers about 26 per cent of Swaziland and is the most densely populated region. The Lowveld: This is the largest region, an area of low relief covering about 37 per cent of Swaziland. The Lubombo Mountains: These extend as a narrow belt along the eastern border of the country. It is the smallest of the regions, covering only 7–8 per cent of the country. It is basically an escarpment and plateau overlooking the Lowveld. Figure 5. The regions of Swaziland. Climate and vegetation With a subtropical climate, more than three-quarters of Swaziland’s rain falls during the summer rainy season (September–March). The mean annual rainfall ranges from less than 550 mm in the driest parts of the Lowveld to 1,500 mm in the wetter parts of the Highveld (Figure 6). The effect of relief on rainfall quantities is strong. The savanna ecosystem occurs over a range of altitudes, from 100 m to 900 m. The highest altitudes occur in the west (adjacent to the grassland ecosystem), dropping gradually to the lowest altitudes in east, but rising again further east in the Lubombo Mountains. At higher altitudes (500–900 m), the vegetation is characterised by tall grassveld with scattered trees and is generally located on steep slopes or rolling hills. At altitudes between 250–500 m, the savanna ecosystem is typically broadleaved woodland on steep to gentle slopes. At the lowest altitudes (100–300 m), the savanna ecosystem is located on basaltic plains and typically supports an Acacia woodland. For every 30 m increase in altitude, there is an increase of about 25 mm in mean annual rainfall. Mean air temperatures show a pattern similar to that of rainfall, with relief being the main controlling factor: air temperature decreases from a peak of 22 °C in the eastern Lowveld to 16 °C in the Highveld. Figure 6. The climate of Swaziland. Savanna vegetation is not immutable and may be altered rapidly by events such as fire. Both the frequency and intensity of fire are important factors. Fire intensity is affected by grazing – as grazing increases, grass cover (which is the primary source of fuel for fires in savanna ecosystems) decreases. This has the effect of reducing the intensity of fire. The elimination of high-intensity fires results in the increased survival of saplings and is termed ‘bush encroachment’. Using and managing the savanna ecosystem The value of Swaziland’s biodiversity has long been recognised by Swazis who make use of it on a daily basis for traditional medicine, food, building materials and traditional clothes. The savanna ecosystem provides Swaziland society with a wide range of goods and services. Figure 7. How the animals and plants of the savanna are used in Swaziland. How plants and animals from the savanna ecosystem are used in Swaziland Food/drink Fodder/grazing Medicine Timber Ornaments Soil/water conservation Handicrafts Clothes Cultural rituals Wildlife viewing Game farming Biological control Many services, such as fuel wood and medicine, are not consumed as goods but are used as part of servicing the wider community (such as pollination, erosion control and flood control). In the past 20 years, game farming has replaced cattle ranching in many parts of southern Africa. This has occurred purely for economic reasons, as game farming is much more profitable. Indigenous game, such as impala and kudu antelopes, are far more suited to surviving in Africa’s drier, marginal landscapes (such as Swaziland’s Lowveld) than cattle. These indigenous species are less susceptible to diseases, require far less water and do not impact negatively on the vegetation. An important direct, but non-consumptive, use of ecosystems is nature-based tourism or ecotourism. Swaziland is generally recognised as a country of great scenic beauty and between 1989 and 1995 over 250,000 tourists per annum have visited Swaziland. Tourists spend about £2 million per annum in the eight largest reserves. This is almost certainly an underestimation as fees are higher in the private reserves. Furthermore, this does not take into account the spin-off benefits of nature-tourism (e.g. money spent on handicrafts, restaurants, etc.), nor does it reflect the number of jobs that are created. Threats to the ecosystem On a regional scale, the savanna ecosystem has the best rate of conservation, with over 8 per cent of the area conserved in South Africa. Nationally, 5 per cent of the savanna ecosystem in Swaziland falls within formally protected areas, and a further 2 per cent is currently managed for wildlife conservation. However, one-quarter of this ecosystem has been converted to some other form of land use, predominantly for the cultivation of sugar cane. In the savanna ecosystem, there are 71 species of threatened plants in comparison to the 161 and 53 endangered species in the grassland and forest ecosystems, respectively. The savanna ecosystem, therefore, is highly diverse, but endemism is low and relatively few species (with the exception of large mammals such as antelopes and their predators) are threatened. There are just seven species of plants and three species of vertebrates that are endemic to the greater Lubombo mountain range. From a resource management perspective, however, 66 per cent of commonly used plant species occur in the savanna areas. On Swazi National Land (land held in trust by the King for the nation), biological resources are used extensively. Wildlife resources (especially antelopes and their mammalian predators) have been decimated in this ecosystem. With the exception of protected areas, and areas under commercial cultivation, the remainder of the savanna ecosystem is heavily utilised for livestock grazing. On Swazi National Land, grazing pressure can be enormous and there are no mechanisms in place to prevent overgrazing. Fauna and flora are utilised both for the preparation of natural medicine and for food. This has led to the destruction of wildlife, and is now contributing to the demise of medicinal plants. Another major threat to this ecosystem is the unsustainable harvesting of wood for timber and fuel. The effects of bush encroachment often include a loss of biodiversity. It has been shown that areas suffering from bush encroachment have a smaller diversity of birds. Alien plant invasion is a problem in parts of this ecosystem, especially along waterways. Finally, parts of the ecosystem have been lost as a result of dam construction. New dam sites are still being proposed in this ecosystem. The role of biodiversity in the national economy Agriculture is the backbone of the economy of Swaziland. Over 80 per cent of Swaziland is dedicated to agriculture. Agricultural production in Swaziland is either done commercially (mainly on title deed land) or on a subsistence basis (mainly on Swazi Nation Land). The main commercial crops grown in Swaziland are: sugar cane – grown by both large-scale companies as well as by medium/small-scale growers; cotton – rain fed (i.e. not irrigated); citrus – grapefruits, oranges and lemons; pineapples; tobacco and maize – both as a commercial and subsistence crop. The full economic value of Swaziland’s biodiversity has yet to be determined. A recent review of the non-timber forestry sub-sector in Swaziland concluded that the economic value of the annual consumption of four chosen product groups (foods and drinks, household items, medicinal plants and fuel wood) is estimated at between £129 million and £514 million. These goods can contribute up to 7 per cent of the GDP. These estimates were considered the absolute minimum value of non-timber forestry products. The Swaziland Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (BSAP) The BSAP process was initiated with the following intentions: To reinforce awareness of the importance of policy reform with particular reference to the conservation of biological diversity. To prepare the ground and identify needs for activities to be undertaken by further biodiversity conservation projects. To draw upon local perceptions about environmental management and to explore alternatives to resource based livelihoods. To integrate these local perceptions with relevant international conventions and undertakings. To stimulate and maintain involvement in the planning of participatory methods of conservation both in situ and ex situ. To help the government of Swaziland to formulate: 1. 2. the National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan; and the country report to the Conference of Parties of the Convention on Biological Diversity. The goals of Swaziland’s BSAP were to ensure: 1. 2. 3. A viable set of representative samples of Swaziland’s natural ecosystems are conserved through a network of protected areas. Biological resources of natural ecosystems outside of the protected areas network are used sustainably. The genetic base of Swaziland’s crops and livestock breeds is efficiently conserved. Figure 8. Lions grazing in a savanna ecosystem. Conservation of the savanna: Nature reserves and game parks There are a total of 17 conservation areas in Swaziland, six of which are legally protected areas. Three areas are controlled by the Swaziland National Trust Commission (Malolotja, Mlawula and Mantenga) and three are big game parks (Mlilwane, Hlane and Mkhaya). These six protected areas are 86 per cent of Swaziland’s conservation areas. The remaining 11 conservation areas have no legal status. This limits their security as conservation areas, as demonstrated by Ubombo Sugar’s plan to cultivate sugar cane on 1 km 2 of land in Mhlosinga Nature Reserve (onequarter of its area). Some of the conservation areas border on each other. For example, Hlane, Mlawula, Shewula, Mbuluzi and Simunye together form an area in excess of 420 km2. Mlilwane and Mantenga are also connected, while Malolotja adjoins Songimvelo Nature Reserve in South Africa to form a transnational conservation area of over 400 km2. With the exception of Mkhaya and Nisela, the remaining conservation areas are all less than 5 km 2, making them too small to support viable populations of most species. The spatial distribution of these conservation areas is not evenly spread across Swaziland. Most of the conservation areas are situated in the east and north of the country, with a shortage of conservation areas in the south and a distinct lack of conservation areas in the southwest. There are numerous obstacles currently preventing the conservation of all of Swaziland’s natural ecosystems: None of the four ecosystems of Swaziland reach the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources’ recommended 10 per cent protection, while three of them (grassland, forest and aquatic) have only 2 per cent within protected areas. No recent field-based surveys have been conducted of areas worthy of protection for their ecosystem. There are insufficient links (i.e. corridors) between ecosystems in different protected areas. Threatened species of fauna and flora require special intervention to prevent their extinction. Protected areas are threatened by alien plant invasion. The protected area network is managed by two separate (non-communicating) authorities. Funding for the management of protected areas is inadequate. Due to insufficient socio-economic incentives, neighbouring communities often do not support protected areas. Attempts to conserve the genetic base of Swaziland’s crops and livestock breeds are difficult because: Indigenous crops are threatened by the use of hybrids and high-yielding varieties. Populations of wild crop relatives are being eradicated through habitat loss. Indigenous livestock breeds are threatened through indiscriminate breeding with exotic breeds. There is a loss of genetic viability within livestock breeds through inbreeding, because of a lack of appropriate breeding policies and programmes. Inadequate research and information are available on indigenous crops and livestock. Figure 9. Table of commercially grown crops in Swaziland. Crop Area under commercial cultivation (km2) Sugar cane 401.31 Cotton 260 Citrus 220 Pineapple 9.18 Tobacco 4 Non-citrus fruit 1.26 Maize not available Beans 61.94 Jugo beans 30.97 Cow peas 27.89 Goundnuts 71.74 Conclusion Savannas can be harsh ecosystems, with drought and fire dictating what species can survive. They are very seasonal ecosystems that appear bountiful in the wet season and quite desolate in the dry season. They contain a large range of plants and animals, a factor that has attracted much human interest. Savannas are important for biodiversity, but they are under increasing pressure from growing populations. Whether they can be protected and preserved is debatable, especially in LEDC regions where the natural environment is seen as a source of free resources.