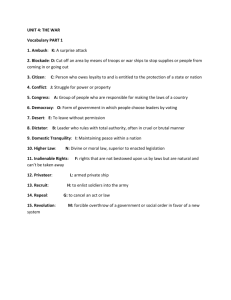

International Report on Question B : Ambush Marketing to smart to

advertisement