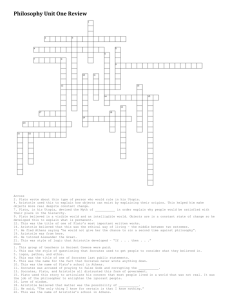

Greek Philosophy

advertisement

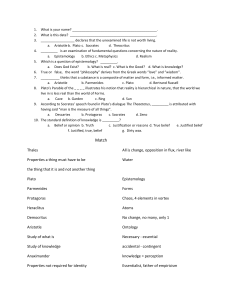

What is Philosophy? Quite literally, the term "philosophy" means, "love of wisdom." In a broad sense, philosophy is an activity people undertake when they seek to understand fundamental truths about themselves, the world in which they live, and their relationships to the world and to each other. As an academic discipline philosophy is much the same. Those who study philosophy are perpetually engaged in asking, answering, and arguing for their answers to life’s most basic questions. To make such a pursuit more systematic academic philosophy is traditionally divided into major areas of study: I. Metaphysics—at its core the study of metaphysics is the study of the nature of reality, of what exists in the world, what it is like, and how it is ordered. In metaphysics philosophers wrestle with such questions as: Is there a God? What is truth? What is a person? What makes a person the same through time? Is the world strictly composed of matter? Do people have minds? If so, how is the mind related to the body? Do people have free wills? What is it for one event to cause another? II. Epistemology—the study of knowledge. It is primarily concerned with what we can know about the world and how we can know it. Typical questions of concern in epistemology are: What is knowledge? Do we know anything at all? How do we know what we know? Can we be justified in claiming to know certain things? III. Ethics—the study of ethics often concerns what we ought to do and what it would be best to do. In struggling with this issue, larger questions about what is good and right arise. So, the ethicist attempts to answer such questions as: What is good? What makes actions or people good? What is right? What makes actions right? Is morality objective or subjective? How should I treat others? IV. Logic—another important aspect of the study of philosophy is the arguments or reasons given for people’s answers to these questions. To this end philosophers employ logic to study the nature and structure of arguments. Logicians ask such questions as: What constitutes "good" or "bad" reasoning? How do we determine whether a given piece of reasoning is good or bad? Greek Philosophy Ancient Greek philosophy is dominated by three very famous men: Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. All three of these lived in Athens for most of their lives, and they knew each other. Socrates was the first of the three “Philosopher Kings”. Plato was his student, and Aristotle was, in turn, his student. Socrates was killed in 399 BCE, and Plato began his work by writing down what Socrates had taught, and then continued by writing down his own ideas and opening a school. Aristotle, who was younger, came to study at Plato's school, and ended up starting his own school as well. Socrates Socrates was the first of the three great Athenian philosophers (alongside Plato and Aristotle). Socrates was born in Athens in 469 BC. He was not from a rich family. His father was probably a stone-carver, and Socrates also worked in stone, especially as a not-very-good sculptor. Socrates' mother was a midwife. When the Peloponnesian War began, Socrates fought bravely for Athens. We do not have any surviving pictures of Socrates that were made while he was alive, or by anyone who ever saw him, but he is supposed to have been ugly. But when Socrates was in his forties or so, he began to feel an urge to think about the world around him, and try to answer some difficult questions. He asked, "What is wisdom?" and "What is beauty?" and "What is the right thing to do?" He knew that these questions were hard to answer, and he thought it would be better to have a lot of people discuss the answers together, so that they might come up with more ideas. So he began to go around Athens asking people he met these questions, "What is wisdom?” "What is piety? " “What is truth?” Sometimes the people just said they were busy, but sometimes they would try to answer him. Then Socrates would try to teach them to think better by asking them more questions which showed them the problems in their logic. Often this made people angry. Socrates soon had a group of young men who listened to him and learned from him how to think. Plato was one of these young men. Socrates never charged them any money. But in 399 BCE, some Athenians became enraged with Socrates for what he was teaching the young men. They charged him in court with impiety (not respecting the gods) and corrupting the youth. People thought he was against democracy, and he probably was—he felt the smartest and most capable people should make decisions for all of society. While Athenians couldn't charge Socrates with being “against democracy,” they could charge him with vague, religious transgressions. Socrates underwent an enormous trial – both in size and in terms of gravity – in front of an Athenian jury. He was convicted of the charges before him and sentenced to death. As was often a method of execution, Socrates was forced to commit suicide by ingesting a cup of hemlock (a poisonous plant) to drink. Socrates never wrote down any of his ideas while he was alive; however, after his death, his student Plato began the feat of preserving Socrates teachings. Plato Plato is known today as one of the greatest philosophers of all time. He was born about 429 BCE, close to the time when Pericles died, and he died in 347 BC, just after the birth of Alexander the Great. Plato was born in Athens, to a very wealthy and aristocratic family. Many of his relatives were involved with Athenian politics, though Plato himself was not. When Plato was a young man, he went to listen to Socrates, and began to ponder how to think, and what sort of questions to think about. When Socrates was killed in 399 BCE, Plato was 30 years - still a young man with a great deal of promise. It was at this time that Plato began to write down the conversations and teachings of Socrates. Practically everything we know about Socrates comes from what Plato wrote down. After a while, though, Plato began to write down his own ideas about philosophy instead of just writing down Socrates' ideas. One of his earlier works is The Republic, which describes what Plato thought would be a better form of government than the government of Athens. Plato thought that most people were pretty stupid, and so they should not be voting about what to do. Instead, the best people should be chosen to be the Guardians of the rest. Plato also thought a lot about the natural world and how it works. He thought that everything had a sort of ideal form, like the idea of a chair, and then an actual chair was a sort of poor imitation of the ideal chair that exists only in your mind. But if chairs have ideal forms, then so do people. The ideal form of a man is his soul, according to Plato. The soul is made of three parts: our natural desires, our will, which lets us resist our natural desires, and our reason, which tells us when to resist our natural desires and when to obey them. For instance, when you are hungry, and you want to eat, that's a natural desire. If you are in the cafeteria at lunchtime, that's a good time to obey your natural desire and go ahead and eat. But if you are hungry in the middle of class, your reason will tell you to wait until lunch, and your will lets you control yourself. When these three parts of your soul are balanced, you will lead a virtuous life, says Plato, answering Socrates' question about what virtue is (arete in Greek). But if the three parts of your soul are out of whack, that leads to wickedness or imbalances in one’s live. If your natural desires are too strong, you will be unable to control your urges and be always acting on pure impulse – doing whatever it is you want without considering the consequences.=. If your will is too strong, it may keep you from listening to your natural desires, like people who use their will to stop eating entirely and become anorexic and starve themselves. And if your reason is not working right, it may tell you to control yourself at the wrong times. Plato's ideas on politics didn't get much attention in Athens, and soon after the death of Socrates he left for Sicily to be the tutor of a young prince there. He tried to bring the prince up to be a good Guardian for his people. But the prince didn't really pay any attention, and after twelve years, now in his mid-forties, Plato gave it up in despair and came back to Athens sadly. Back in Athens, Plato started a school for philosophers, called the Academy. The Academy was a big success, and Plato stayed there for the rest of his life, another forty years. One of Plato's students at the Academy was Aristotle. Plato spent a lot of the last part of his life writing another political piece called The Laws, which is much more pessimistic than The Republic, and talks more about how corrupt politicians are, and how they have to be watched every minute. Plato died at 82, in 347 BCE. His students at the Academy preserved and copied all of his writings, so that we have a pretty complete record of everything Plato wrote. Aristotle Aristotle's father was Nicomachus, a doctor who lived near Macedon, in the north of Greece. So unlike Socrates and Plato, Aristotle was not originally from Athens. He was not from a rich family like Plato, though his father was not poor either. When Aristotle was a young man, about 350 BCE, he went to study at Plato's Academy. Aristotle did very well at the Academy. But he never got to be among its leaders, and when Plato died, the leaders chose someone else instead of Aristotle to lead the Academy. Soon afterwards, Aristotle left Athens and went to Macedon to be the tutor of the young prince Alexander – later known as Alexander the Great. As far as we can tell, Alexander was not terribly interested in learning anything from Aristotle, but they did become friends. When Alexander grew up and became king, Aristotle went back to Athens and opened his own school there, the Lyceum, in competition with Plato's Academy. Both schools were successful for hundreds of years. Aristotle was more interested in science than Socrates or Plato, maybe because his father was a doctor. He wanted to use Socrates' logical methods to figure out how the real world worked; therefore Aristotle is really the father of today's scientific method. Aristotle was especially interested in biology, in classifying plants and animals in a way that would make sense. This is part of the Greek impulse to make order out of chaos: to take the chaotic, natural world and impose a man-made order on it. When Alexander was traveling across Western Asia, he had his messengers bring strange plants back to Aristotle for his studies. Aristotle also made efforts to create order in peoples' governments. He created a classification system of monarchies, oligarchies, tyrannies, democracies and republics which we still use today. When Alexander died in 323 BCE, though, there were revolts against Macedonian rule in Athens. People accused Aristotle of being secretly on the side of the Macedonians (and maybe he was; he was certainly, like Plato, no democrat). He left town quickly, and spent the last years of his life back in the north where he had been born. Reading Quiz: Philosophy Name: ____________________________________________________________ Points: ______/10 1. What is philosophy? 2. What are the four traditionally identified branches of philosophy? 3. Who were the philosopher kings? 4. Why did Socrates enrage the people of Athens? 5. What happened to Socrates because he enraged the people of Athens? 6. Although Socrates did not write down any of his teachings or knowledge himself, we know a great deal about him. How do we know so much about Socrates despite not having any of his writings? 7. How did Plato feel about democracy (the Athenian form of government)? 8. What was the name of the school started by Plato? 9. Who did Aristotle tutor? 10. Identify on of the many scientific advancements that Aristotle made during his life.