“Antigone” Close Reading

advertisement

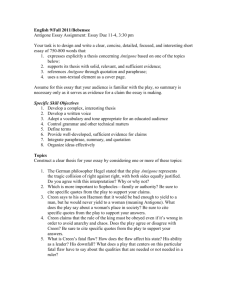

“Antigone” Study Guide Greek Theater Greek tragedies and comedies were always performed in outdoor theaters. Early Greek theaters were probably little more than open areas in city centers or next to hillsides where the audience, standing or sitting, could watch and listen to the chorus singing about the exploits of a god or hero. From the late 6th century BC to the 4th and 3rd centuries BC there was a gradual evolution towards more elaborate theater structures, but the basic layout of the Greek theater remained the same. The major components of Greek theater are labeled on the diagram above. Orchestra: The orchestra (literally, "dancing space") was normally circular. It was a level space where the chorus would dance, sing, and interact with the actors who were on the stage near the skene (see explanation below).The earliest orchestras were simply made of hard earth, but in the Classical period some orchestras began to be paved with marble and other materials. In the center of the orchestra there was often a thymele, or altar to Dionysus. The orchestra of the theater of Dionysus in Athens was about 60 feet in diameter. Theatron: The theatron (literally, "viewing-place") is where the spectators sat. The theatron was usually part of hillside overlooking the orchestra, and often wrapped around a large portion of the orchestra (see the diagram above). It held as many as 16,000 citizens. Spectators in the fifth century BC probably sat on cushions or boards, but by the fourth century the theatron of many Greek theaters had marble seats. Some say that only male, free Greeks were allowed to attend the plays, while others assert that women and slaves were allowed to 1 sit in certain reserved sections of the theater. State officials, priests, and dignitaries sat in the front row. Skene: The skene (literally, "tent") was the building directly behind the stage. During the 5th century, the stage of the theater of Dionysus in Athens was probably raised only two or three steps above the level of the orchestra and was perhaps 25 feet wide and 10 feet deep. The skene was directly in back of the stage and was usually decorated as a palace, temple, or other building, depending on the needs of the play. It had at least one set of doors, and actors could make entrances and exits through them. There was also access to the roof of the skene from behind, so that actors playing gods and other characters could appear on the roof, if needed. Parodos: The parodoi (literally, "passageways") are the paths by which the chorus and some actors (such as those representing messengers or people returning from abroad) made their entrances and exits. The audience also used them to enter and exit the theater before and after the performance. Staging an ancient Greek play Attending a tragedy or comedy in 5th century BC Athens was in many ways a different experience than attending a play in the United States in the 20th century. To name a few differences, Greek plays were performed in an outdoor theater, used masks, and were almost always performed by a chorus and three actors (no matter how many speaking characters there were in the play, only three actors were used; the actors would go back stage after playing one character, switch masks and costumes, and reappear as another character). Greek tragedies were at first wholly lyrical. Greek plays were performed as part of religious festivals in honor of the god Dionysus, and unless later revived, were performed only once. Plays were funded by the polis, and always presented in competition with other plays, and were voted either the first, second, or third (last) place. Playwrights Three Greek tragedians are still celebrated today as some of the most successful playwrights in history and are each noted for specific contributions to Greek Theater. During the festival each of these playwrights typically had one day to present his works with prizes distributed at the end of the festival. Aeschylus (525 B.C. - 426 B.C.) introduced a second actor which made possible dialogue independent of the chorus. He wrote his plays in trilogies, three based on a single story or theme. These three tragedies, along with a satyr play (a type of comic relief) were performed on a given day of the festival. 2 Sophocles (496 B.C. - 406 B.C.) wrote 123 dramas; seven still exist. He won fame in his early 20’s at his first competition when he defeated Aeschylus. He was the first playwright to add a third actor and increased the size of the chorus to fifteen. He also introduced the use of painted scenery. Antigone belonged to the Oedipus cycle. Antigone was introduced in 441 B.C., Oedipus Rex in 430 B.C., and Oedipus at Colonus in 401 B.C. (after Sophocles’ death). Thus, Sophocles did not follow the tradition of Aeschylus’ in presenting interrelated themes as contest entries. After his death, he was honored as a hero. Euripides (480 B.C. - 406 B.C.) is referred to as the most tragic of the three great playwrights. He sought to humanize characters and make conflict more realistic. He reduced the role of the chorus by detaching it from the main action. He employed the device of opening drama with a speech reviewing events and was known for his overuse of ending his plays with intervention from heaven Structure of the Plays The basic structure of a Greek tragedy is fairly simple. After a prologue spoken by one or more characters, the chorus enters, singing and dancing. Scenes then alternate between spoken sections (dialogue between characters, and between characters and chorus) and sung sections (during which the chorus danced). Here are the basic parts of a Greek Tragedy: a. Prologue: Spoken by one or two characters before the chorus appears. The prologue usually gives the mythological background necessary for understanding the events of the play. b. Parodos: This is the song sung by the chorus as it first enters the orchestra and dances. c. First Episode (Scene in Antigone): This is the first of many "episodes", when the characters and chorus talk. d. First Stasimon (Ode in Antigone): At the end of each episode, the other characters usually leave the stage and the chorus dances and sings a stasimon, or choral ode. The ode usually reflects on the things said and done in the episodes, and puts it into some kind of larger mythological framework. For the rest of the play, there is alternation between episodes and stasima, until the final scene, called the... e. Exodos: At the end of play, the chorus exits singing a processional song which usually offers words of wisdom related to the actions and outcome of the play. 3 Greek plays generally followed what Aristotle called the three unities. Unity of action demanded a single action with no subplots or irrelevancies; unity of time limited the action to a 24 hour period, and unity of place decreed one unchanging scene. Classical Greek Drama Read pages 1064-1065 and answer the following questions: 1. What is a classical drama? 2. Who were the actors in Greek dramas? 3. What did the actors wear? 4. Describe the chorus: 5. Who is the choragus? 6. What did the chorus mainly communicate? 7. Define tragedy: 8. Define tragic hero: 9. What usually causes a tragic hero’s downfall? 4 5 6 Greek Drama Literary Terms (Aristotle’s Poetics) 1. peripeteia: reversal of fortune 2. strophe: chanted as the chorus moves from right to left across the stage 3. anagnorisis: recognition or discovery on the part of the hero; change from ignorance to knowledge 4. antistrophe: chanted as the chorus moves back across the stage from left to right. 5. nemesis: fate that cannot be escaped 6. hamartia: the “crime” or “sin” committed in ignorance of some material fact or even for the sake of a greater good. This is not the same as the tragic flaw. 7. hubris: arrogance or overweening pride which causes the hero’s transgression against the gods. 8. parados: the first ode in a Greek tragedy, chanted by the chorus as it enters the orchestra 9. tragic hero: a high-born character whose downfall is brought about by a weakness or error in judgment 10. Choragus: leader of the chorus 11. tragedy: an imitation of a serious action which will arouse pity and fear in the viewer 12. catharsis: purgation of emotions of pity and fear which leaves the viewer both relieved and elated. 7 Prologue 1. Compare the syntax of Antigone and Ismene in lines 1-10. What do Antigone’s quick sentences reveal about her character? What does Ismene’s longer paragraph reveal about her character? 2. After describing the details of Creon’s decree, Antigone presents the alternatives to Ismene. (Line 25) What word with strong connotations does Antigone use? __________________ What tone is conveyed through Antigone’s word choice? 3. Antigone asserts, “Creon is not strong enough to stand in my way” (line 35). What does this statement reveal about her character? 4. What event does Ismene allude to in lines 36 –42? 5. In lines 45-52 what arguments does Ismene provide against Antigone’s plan? ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ 6. What does Ismene’s choice of words, “meddle” reveal about her views of her own role and ability to fight against Creon? 7. Which literary technique is used in Antigone’s statement that her “crime is holy”? 8. At line 60, Antigone provides her reasoning for burying Polyneices. What is it? 8 9. In the next passage, what does Ismene reveal about her thoughts about the law? 10. Antigone and Ismene’s contrast to one another causes them to be ______________. 11. Compare Antigone’s tone to Ismene’s in the last passages of the scene. Parados 1. What type of figurative language is used to describe “long blade of the sun…”? _____________________What is the purpose of such a comparison? 2. As indicated in the quote, “Open, unlidded eye of golden day!” what type of figurative language is used to describe the sun? 3. What effect has the bright morning light had on the attacking enemy of Thebes? 4. Polyneices is compared to what type of animal? What image is conveyed by the comparison? 5. The Theban guard, fending off Polyneices’ attack, is compared to what? 6. The Choragus’ use of word like “bray, “bragging,” and “swaggering” reveal what attitude toward the attacking troops? 7. The Choragus implies that the Thebans’ cause is more just than that of the attacking troops through which quotes? 9 8. Which god is referred to as the “god/That bends the battle-line and breaks it”? 9. The repetition of the “b” sound in the same passage uses which sound device? How does its use enhance the sound of combat, as described by the Choragus? 10. What is the tone of lines 39-43? Which words and passages convey the tone? 11. The chorus’ belief that Thebes will, “take leave of war” reflects what expectation? 12. Contrast the tones of the Prologue and the Parados. Scene 1 1. What is the meaning of “auspicious,” as spoken by the Choragus’ speech? ________________________What tone is reflected through the choice of words? 2. What type of figurative language does Creon use to describe the welfare of Thebes? 3. Why do you think Creon gives a review of history? (Lines 10 – 20) 10 4. Creon’s principles are given in lines 20 – 35. He has contempt for ______________, no use for ______________________, and no dealings with __________________. 5. Creon’s assertion that “Friends made at the risk of wrecking our ship are no real friends at all” refers to whom? 6. What decision has Creon made regarding Eteocles’burial and Polyneices’ burial? 7. How are Creon’s tones different at the end and beginning of his address to the Chorus? 8. Based on the Choragus’ response, what can you infer he feels about Creon’s decision? 9. “Only a crazy man is in love with death” alludes to the upcoming actions of which character? 10. Creon’s response in lines 63-65 that “Money talks…” reflects his belief that all men are capable of what? 11. What does the Sentry’s rambling, bumbling speech provide after the somber and serious passages preceding it? 12. Although the Sentry does not know who buried Polyneices, nor does Creon, the audience does. What type of irony is reflected through this knowledge? 13. What effect does the Choragus’ implication that the gods have become involved have on Creon? Why? 14. Creon’s response to the Choragus’ doubt reveals his true feeling about the Theban elders. Which words reflect his true sentiments? 11 15. Creon believed that __________________________ had disobeyed his orders. Why? 16. Of whom did he suspect the same fault earlier in the scene? 17. Based on Sophocles’ development of Creon at this point in the drama, what seem to be his strengths and weaknesses? 18. What quality did the Sentry see in Creon, as revealed in the statement, “How dreadful it is when the right judges judge wrong”? 19. Did the Sentry plan or returning, as commanded by Creon? Why or why not? Ode 1 1. Summarize the main points of the Ode. 2. Who does the Chrous favor: the lawmaker or lawbreaker? 3. What opinion does the Chorus express regarding the importance of law in society? 4. If “law” refers to civil law, who is the anarchist? If “law” refers to the gods’ laws, who is the anarchist? 12 Scene 2 1. As the scene opens, the Sentry has reappeared. How has his attitude toward Creon changed from the previous scene? Why? 2. Who has the Sentry arrested as the culprit guilty of burying Polyneices? 3. In the passage used to describe the setting in which the Sentry discovered Antigone, which rhetorical strategies were used? (Lines 25 – 35) 4. To what does the Sentry compare Antigone upon finding her work undone? _______________What tone toward Antigone is conveyed through the comparison? 5. What do you notice about the action the Sentry describes in lines 25 – 45? (Where does it take place?) How does this relate to the stage and set of ancient Greece? 6. On what basis does Antigone justify the burial of Polyneices? 7. Antigone’s assertion that Creon’s edict “was strong/ But all you strength is weakness against itself” is best described by which literary technique? 8. Through Antigone’s words, Sophocles gives life to death, crime and anarchy. Find examples that personify each in lines 65 – 95. 9. The Chorus compares Antigone’s actions to those of which other character? 10. What is Creon inferring about Antigone through the comparisons to tough iron and wild horses? 11. Summarize Creon’s views on family versus duty as expressed in line 82 – 85. 13 12. According to Creon, whose crime is worse, Antigone’s or Ismene’s? 13. List two examples of figurative language that Antigone uses to express the elders’ fear of Creon? 14. Contrast Antigone and Creon’s view of honor and burial as revealed in lines 105 –115. 15. The Choragus compares Ismene’s sorrow to what? Creon compares her actions to what? 16. Find a quote that emphasizes Antigone’s rejection of Ismene’s belated involvement in the “crime”. 17. What is a martyr? How does Antigone fit the description of a martyr? 18. Antigone and Ismene are cast as foils. How do the words of Creon and Ismene is lines 148 – 151 reinforce this concept? 19. What fact about the relationship between Antigone and Haemon does Ismene reveal at line 155? 14 20. Ismene speaks to Creon’s son, Haemon, even though he is absent from the scene. Which literary term reflects this type of address? 21. Creon rejects responsibility for Antigone’s death, instead casting the blame on whom or what? Ode 2 1. Summarize the main ideas of Ode 2. 2. How does the sin of moral arrogance apply to both Antigone and Creon? Scene 3 1. Creon’s belief that Haemon must either hate or love him reflects what quality of his character? 2. As reflected in lines 8-10, what is Haemon’s attitude toward his father? 3. Creon’s choice of words, “subordinate,” reflects what attitude toward the father-son relationship? 4. Which other words in the passage convey similar ideas? 5. Creon gives Haemon advice on dealing with women, even though he shows little skill in doing the same. Which literary technique does this reflect? 15 6. What is Creon’s view of government, as stated at line 35? 7. How can his views be applied to Antigone’s situation? 8. As suggested in lines 40 – 50, of what two things does Creon seem to be afraid? 9. What are Haemon’s main ideas regarding public opinion? 10. What is Haemon’s tone toward his father in the speech beginning with “Reason is God’s crowning gift…”? 11. What types of comparisons does Haemon use in an attempt to sway his father’s mind? 12. Creon refuses to listen to Haemon’s reasoning based on his youth and emphasizes his disdain for Haemon’s lack of experience through what word? ____________ What connotations are associated with this word? What tone does it suggest? 16 13. According to Haemon, what is the role of the king; what is it according to Creon? 14. How does Haemon’s use of the word “desert” apply to Creon’s style of leadership? 15. Creon’s exclamation that “Every word you (Haemon) say is for her!” might reflect what character trait? 16. How does Creon interpret Haemon’s statement that “her (Antigone’s) death will cause another”? 17. How has Haemon’s attitude toward his father changed since the scene’s opening? 18. How does Creon plan to free the State from any culpability in Antigone’s death? Ode 3 1. Ode 3 begins as an address to whom or what? 2. Love is characterized as what type of force? 3. Which words emphasize this idea? Scene 4 17 1. What is occurring as the scene begins? 2. What is “that chamber/Where all find sleep at last” to which the Choragus refers? 3. What emotions do the Chorus express as Antigone is led to her death? 4. How do the tones of Antigone and the Chorus contrast in lines 5 –15? 5. Sophocles alludes to Niobe and Tantalus because, like Antigone, they have done what? 6. How is Antigone’s tone different in lines 25 – 35 than in earlier scenes? Specifically, what is her attitude toward her actions and her punishment? Which words emphasize the difference? 7. Antigone’s cry, “O, Oedipus, father and brother! /Your marriage strikes from the grave to murder mine,” even though Oedipus is absent from the scene is best termed an/an __________________________________? 8. Which rhetorical or literary technique is reflected in Antigone’s assertion that she has been “a stranger in my own land”? 9. What is the meaning of blasphemy, as used in line 44? (look it up!) What connotations are associated with the word? How does use of the word intensify Antigone’s speech in the passage? 18 10. What reminder does the Chorus issue as Antigone seeks pity for her fate? 11. Which sound device is reflected in Antigone’s realizations that she will find “Neither love nor lamentation; no song, but silence” in her death? 12. Antigone’s reminder to the elders that instead of death she should be starting a new life with Haemon reflects which literary technique? 13. Lines 66 – 70 introduce an element of foreboding. What does Antigone say that might be played out in future scenes? 14. How does the Choragus characterize Antigone’s final speeches? 15. Overall, what was the Chorus’ tone toward Antigone as revealed in Scene 4? 16. In Ode 4, the Chorus alludes to mythical characters that have dealt with fate. What lessons did Danae, Lycurgos, and the new wife of King Phineus learn about fate? 17. How does Antigone fit the idea that no mortal can escape Fate’s reach? 19