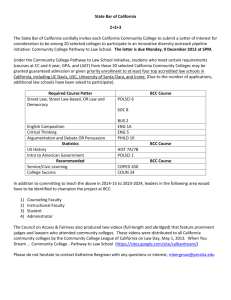

US/Mexico Border Crossing Cards (BCCs)

advertisement