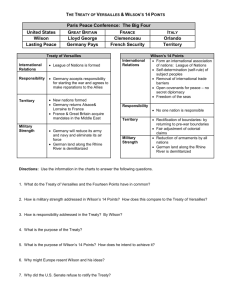

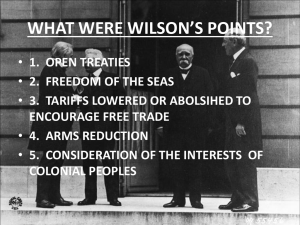

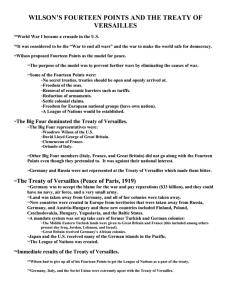

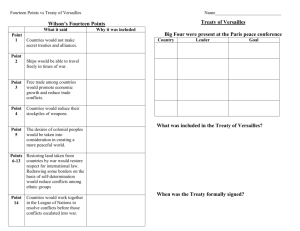

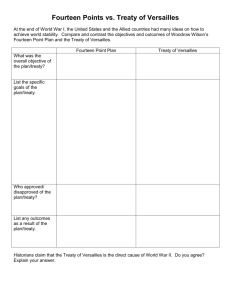

The Treaty of Versailles

advertisement