Two Views of Andrew Jackson`s Indian Removal Policy

advertisement

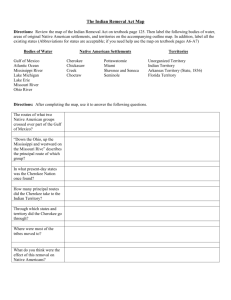

Two Views of Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Policy “Do the obligations of justice change with the color of the skin?” by Howard Zinn, rewritten from Chapter 7 of A People’s History of the United States After Andrew Jackson was elected President in 1828, the Indian Removal Bill came before Congress and was called, at the time, “the greatest question that ever came before Congress.” As soon as Jackson was elected President, Georgia…began to pass laws intended to put the Cherokee under state rule. However, federal treaties and federal laws gave Congress, not the states, authority over the tribes. The Indian Trade Act of 1802 said there could be no land cessions except by a federal treaty with a tribe and said federal law would operate in Indian territory. Andrew Jackson ignored this and supported state action. It was a neat illustration of the uses of the federal system by the president: depending on the situation Jackson could support state action (as he did with the state of Georgia against the Cherokee) or he could support federal action (he refused to recognize South Carolina’s right to reject, or “nullify” a federal tariff that same year). As Jackson took office in 1829, gold was discovered in Cherokee territory in Georgia. Thousands of whites invaded, destroyed Indian property, and illegally staked out land claims. Jackson would not protect the Cherokee…because (he said) he could not interfere with the state of Georgia’s authority in this matter. With 17,000 Cherokee’s surrounded by 900,000 whites in Georgia and surrounding states…the Cherokee had decided years ago that survival meant adaptation to the white man’s world. They became farmers, blacksmiths, carpenters, and owners of property. A census of 1826 showed 22,000 cattle, 7,600 horses, 172 wagons, 10 saw mills, 62 blacksmith shops, 8 cotton machines, and 18 schools. Their chief, Sequoyah, invented a written alphabet, which thousands learned. They printed a newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix, in both English and Sequoyah’s Cherokee. The Cherokee even started to copy the slave society around them: they owned more than a thousand slaves. They were beginning to resemble the civilization the white man spoke about, making what Van Every (historian and biographer) calls a “stupendous effort” to win the good will of Americans. They even welcomed missionaries and Christianity. None of this, however, made them more desirable than the land they lived on. As the Indian removal bill came before Congress, there were several proud defenders of the Indians. Senator Theodore Frelinghuysen of New Jersey, eloquently told the Senate: “We have crowded the tribes upon a few miserable acres on our Southern frontier; it is all that is left to them of their once boundless forest (was taken): and still, like the horse leech, our cries (for more land)-Give! Give!…Do the obligations of justice change with the color of the skin?” The North was in general against the removal bill. The South was for it. It passed the House 102 to 97. It also narrowly passed the Senate. It provided for helping the Indians to move…but if they did not, they were without protection from the federal government, without funds, and at the mercy of the state of Georgia. The Cherokee nation resisted and addressed a memorial to the nation, a public plea for justice. They reviewed their history: “We wish to remain on the land of our fathers. The laws of the United States guarantee our residence. Our only request is that these treaties may be fulfilled.” Then they went beyond history, beyond laws: “We ask to remember the great law of love-Do unto others as you would have others do unto you. We pray to those who ask us to leave, to remember that when your forefathers were driven from the Old World (Europe) over the great waters and onto the shores of the New World, that they remember how they were received by the Indians, who had power in their hands.” Jackson’s response to this was that many of the other tribes had already moved, and that speedy removal was in the best interest of everyone. The state of Georgia then passed a law that forbid whites from assisting the Cherokee. When a white missionary, Samuel Worcestor, was arrested by Georgia militia for helping the Cherokee, he was sentenced to four years of hard labor (after bravely refusing to take an oath of allegiance to the state of Georgia which would have freed him). This was appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States in 1832, and in Worcestor v. Georgia, Chief Justice John Marshall declared that the state of Georgia had no legal right to make laws over the Cherokee. Since federal law existed with the Cherokee, the Constitution was binding on the states. Andrew Jackson refused to enforce the court order and remarked, “John Marshall has made his decision…let him enforce it.” And so the Cherokee nation, with its newspaper banned, its government dissolved, their white missionaries jailed…did not resort to violence, despite ongoing attacks from Georgia whites. Weary of the struggle, by 1834 seven hundred of the Cherokee agreed to go west. Eighty-one died en route, including forty-five children. Those who lived arrived at their destination across the Mississippi during a cholera epidemic and half would die within a year. In 1836, less than 500 Cherokee (out of 17,000) signed a treaty agreeing to move. Eloquent objections came from white poets such as Ralph Waldo Emerson (“this decision will make us…stink to the world”), but removal proceeded. Congress approved the treaty, and even the Congressmen who defended the Cherokee lost hope. To convince any Cherokee still unsure about leaving, white plantation owners stepped up their attacks. In late 1838, the seventeen thousand Cherokee were rounded up and crowded into stockades (where the cattle had been held). On October 1, 1838, the first detachment set out in what was to be known as the “Trail of Tears.” As they moved westward, they began to die-of sickness, of drought, of the heat, of exposure to severe cold. There were 645 wagons, and people marching alongside. Survivors, years later, told of halting at the edge of the Mississippi in the middle of winter, the river running full of ice, “hundreds of sick and dying penned up in wagons or stretched upon the ground.” Estimates that during the confinement in stockades or on the march over four thousand Cherokee died. In December 1838, new President Van Buren (Andrew Jackson’s chosen successor) spoke to Congress: “It (is of) sincere pleasure to inform the Congress of the entire removal of the Cherokee Nation to their new homes west of the Mississippi. The measures authorized by Congress have had the happiest effects.” Under Jackson and Van Buren…ultimately seventy thousand Indians east of the Mississippi were forced Westward. “The Only Answer” by Robert Remini, rewritten based on his book, The Life of Andrew Jackson Andrew Jackson’s commitment to the principle of Indian removal resulted primarily from the concern for the safety and integrity of the entire American nation. It was not greed or racism that motivated him. He was not intent on genocide (the mass deaths in the “Trail of Tears”). He was not involved in a gigantic land grab for the sake of the people of Georgia…or anyone else…He had come to the unfortunate-but unavoidableconclusion that the only policy that benefited both people’s, red (Indian) and white, was removal. The extinction of the American Indian, in his mind, was inevitable unless removal was the official policy of the American government. To Andrew Jackson, the policy of removal was the only answer to the hostility that existed between the white and red races. And to the large extent, the policy was adopted to protect the Indians and their culture against inevitable extinction if they stayed where they were. The only way to prevent the disappearance of Native cultures was to give them their own land where they could preserve what remained of their culture. Given the conditions that existed in the United States in the 1830s, it is likely that Indian cultures would have either been completely assimilated and absorbed (which was already happening to the Cherokee), or violently exterminated. Jackson and the federal government did not have the power to protect Indian people in the states (like Georgia) that were opposed to federal government involvement in this issue. Furthermore, Jackson knew that the rapid growth of the United States required that old treaties with Native Americans be reconciled (re-evaluated). Indians could no longer be treated as separate nations; to do so meant having separate countries within the nation’s larger borders. It was simply inconsistent with the principles of government to continue doing so. Indians lived within the territory of the United States, and the only way to ensure their protection (and survival) was to make them subject to government laws. Questions to consider: 1. Do you think Zinn’s view of Jackson is fair? Analyze and explain. 2. Do you think Remini’s defense of Jackson is justified? Why or why not? 3. Evaluate each historian’s perspective. If you were a Congress member during this time period would you have voted to pass the Indian Removal Bill and move the Native American’s westward? Justify your decision with historical evidence and analysis.