European Higher Education Seeks a Common Currency

advertisement

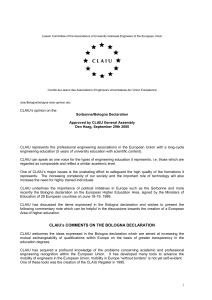

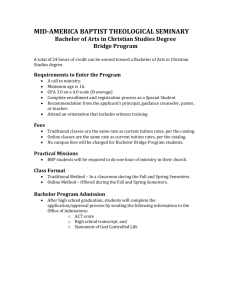

European Higher Education Seeks a Common Currency But some professors oppose a plan to standardize degrees and course credits By BURTON BOLLAG http://chronicle.com Section: International Volume 50, Issue 5, Page A52 Vienna A quiet revolution is shaking the foundations of European higher education. Countries are abandoning their national degree systems -- mostly adopted in the 19th century and largely incompatible -- and introducing new ones based on a single model: a three-year bachelor's degree and a two-year master's. Nations are also introducing a standard credit system to make it easier for course work completed at one university to be recognized by another. The transformation is known as the Bologna process, after the city in which officials of 29 countries met in 1999 and signed a declaration pledging to create a common European Higher Education Area by 2010. The process of reform, which is being pushed by governments and university presidents throughout Europe, is arduous, and some students and faculty members have resisted the change. The signed declaration has helped create political leverage for administrators to shorten the lengthy initial degree programs -- which often require six or more years of study -- that some professors have favored. Supporters say the process is the key to modernizing old-fashioned university systems and allowing them to make a real contribution to the unification of Europe. Lesley Wilson, secretary general of the Brussels-based European University Association, says Europe may appear to be copying central elements of the American higher-education system. "Superficially, yes," she says. "But it's about Europe finding a system that's more flexible. You have to break up the structure of long degrees in which students don't have the possibility of stopping their studies before five or six years. You need a common degree structure to make it easier for students to continue their studies or find jobs in other European countries. And it's clear Europe needs to make itself more attractive to foreign students." Europe Divided The Bologna process comes on top of great strides already made to integrate Europe politically and economically. Passports are no longer required for travel between most of the 15 European Union countries. Last year a single currency, the euro, was introduced in 12 of them. Next spring the European Union will expand eastward by accepting 10 new members -mostly former communist states. A European constitution is being drafted. But even now, higher education remains a chaotic jumble of unrelated national systems, until recently jealously guarded and off limits to reformers' efforts. In Belgium, for example, students must first earn a two-year candidat degree before beginning another two-year stint required for their licence, roughly the equivalent of a bachelor's degree. Most British undergraduates pursue a three-year bachelor's degree; some go on to earn a one-year master's. Until Italy abruptly scrapped it two years ago, the first degree a student could earn, called the laurea, was roughly the equivalent of a master's degree in the United States. The laurea typically took seven or eight years to complete, and earned graduates the right to be called dottore, or doctor. The shortening of the initial degree program is often cited as one of the key benefits of the reforms. Although degree programs taking up to seven or eight years to complete did not pose a problem when only an elite minority pursued higher education, they are increasingly seen as impractical and unnecessarily expensive now that universities are enrolling greater numbers of students. With no way out until the end, these programs are typically plagued by high dropout rates. Thirty-three countries have now pledged to carry out the Bologna reforms, and almost all have adopted legislation phasing in the new degree structure in place of their traditional ones. If Albania and three former Yugoslav republics also sign up at a meeting of European education ministers in Berlin this week, as expected, almost every country in Eastern and Western Europe will have endorsed the reforms. Attracting Foreign Students Yet nations are eager to maintain control over their higher-education systems. What is being created, supporters stress, is not a standard European system, but compatibility among independent national systems. For example, the Bologna process stipulates only that the new bachelor's and master's degree programs combined must take five years of full-time study. A few countries have chosen to create a four-year bachelor's and one-year master's degree, but the "three plus two" model is clearly emerging as the norm. Having a common and easily understandable degree structure, academics say, will help make higher education in Europe more attractive to foreign students because it will be viewed as essentially a single system with a clear identity. Continental Europe, in particular, is hoping the new system will help it compete with Australia, Britain, and the United States for foreign students. Britain has signed on to the Bologna process, but already attracts thousands of foreign students. During the last few years, universities on the continent have watched forlornly as the growing number of young Asians going abroad to study have chosen institutions in those Englishspeaking countries. According to the most recent official figures, in 1999, for example, 302,000 people from Asia studied in the United States or Canada. Only 178,000 enrolled at universities in the European Union -- and a large number of them went to Britain, which doesn't have to go to the trouble of developing programs in English to attract foreign students. Backers say the purpose of the agreement goes deeper than simply devising a common degree structure. In place of Europe's traditionally rigid study programs, reformers are seeking "learner-centered education, where you can combine different subjects, accumulate credits, interrupt your studies, and come back at different times during your life," says Christian Tauch, an expert on the reforms with the German Rectors Conference, which represents the administrations of the country's many public universities. At the University of Vienna, for example, typically three-quarters of the classes in a degree program are mandatory, and students can choose from only a small number of electives for the rest. Until very recently, if a university wished to change a single course in a degree program, it needed authorization from the education ministry. Mixed Success Most countries have passed laws mandating the switch to the new degree system, with Austria, the Netherlands, and Norway among the countries rapidly phasing in the changes. But others are lagging behind. Germany, for example, is leaving it up to institutions to decide whether to retain traditional master's-level initial degrees or introduce the new ones. And even when university leaders order the changes, they sometimes discover that departments, which traditionally enjoy considerable autonomy in Europe, don't listen. "We've tried to persuade departments by pointing to the advantages" of the new degree structure, says Arthur Mettinger, vice rector of the University of Vienna. He believes that the shorter undergraduate program will appeal to students who prefer to move into the work force relatively quickly, while those who want to continue their studies will have a greater choice of master's programs. At the University of Vienna, as soon as a department introduces the new three-year bachelor's and two-year master's degree programs, all new students are automatically enrolled in the new system. As of this fall, one-quarter of Vienna's 70,000 students are studying for a bachelor's or master's degree instead of the magister, which takes six or seven years to earn. Yet some departments, Mr. Mettinger admits, are resisting the changes. He stresses that departments are being asked not just to split in two the traditional initial degree -- the magister, which generally takes six or seven years to complete -- but to develop new academic programs. The Bologna process should be used as "a lever to modernize content," he says. Moreover, according to the Bologna protocol, the new bachelor's degrees should be "relevant to the European labor market." In other words, they should qualify graduates for jobs. In its new bachelor's programs in biology, for example, the University of Salzburg has deemphasized zoological and botanical classification, and added new courses in molecular biology, which is central to genetic engineering and DNA fingerprinting. Doubts Abound But in Austria and many other countries, students and employers have doubts about the value of a shorter undergraduate degree. "We have no assurance that the bachelor's degree will lead either to a job or a master's program," says Werner Hromada, spokesman for the five student members of the University of Vienna's Senate. Ultimately, says Ulricke Felt, a professor of the social studies of science at Vienna, who has written extensively about higher education reform, the concerns are over the educational philosophy behind the changes. "People are asking," she says, "will you still have a broad education or just training for a job?" In a few countries, students have fiercely opposed abandoning the traditional degrees. Last year about 35 members of Switzerland's national student union invaded a meeting of highereducation officials to protest plans to introduce the Bologna reforms there. The students were particularly incensed by proposals to set tuition for master's programs higher than those for bachelor's degrees, a move which they say would create an obstacle to graduate study. The Bologna process "was always sold as a reform aimed at increasing mobility," says Thomas Frings, head of the country's national student union. "But it's a lie. The reforms are being used to reduce state spending in higher education." In a few cases, professors have led the resistance to change. In May 2002, faculty members at Greece's two dozen public universities went on strike several weeks before the end of the academic year, forcing a postponement of year-end exams, to demand better salaries and an end to the Bologna reforms. "Three years is not enough" for the initial degree, says Filarete Zafiropoulou, an assistant professor of mathematics and head of the faculty association at the University of Patras. "Of course, doing a master's degree in another country would be easier if all first degrees were equivalent. But this should not be done at the expense of students' academic training." Some educators are simply not convinced that the new degree structure represents an improvement over the old one. "The quality and contents [of the old and new programs] will be just the same," says Ivan Ostrovsky, vice rector of Comenius University in Bratislava, Slovakia's leading higher-education institution. Yet his institution is going along with the reforms anyway. "You can't be an island in Europe," explains Mr. Ostrovsky. He says he doesn't want Slovakia's young people to face barriers when they seek graduate study or jobs in the European Union, which Slovakia is joining in May. Crossing Borders Removing barriers is one of the chief benefits that backers say the reforms will bring. Over the last decade, the European Union has done much to promote student exchanges. Last year 120,000 students completed a semester or two of their studies in another European country through the EU's Erasmus program. But recognition of academic credit has to be painstakingly worked out between the home and foreign institution on a case-by-case basis. Introducing similar degree structures should make the task easier. The move should open up the possibility of large numbers of students pursuing a bachelor's degree in their own country, then choosing an institution in another European nation for their master's studies, giving them a much greater choice of graduate programs. A growing number of universities are developing master's programs in English, making foreign study more feasible for many. European countries are rapidly adopting other mechanisms for increasing academic mobility in recent years as well. The standard European Credit-Transfer System provides a common method for transferring credit for academic work completed in a foreign institution. And "diploma supplements," documents that accompany transcripts, provide institutions and prospective employers with more detailed information on foreign course work. Yet the changes often do not come easily. The new credit system assigns credits to courses based on the student workload, while the old system weighted every course equally. Karin Riegler, the official in charge of the Bologna reforms for the Austrian Rectors Conference, which represents the administrations of the institutions in Austria's mostly public university system, says full professors may see their lectures given fewer credits than seminars taught by less-senior colleagues. "For older faculty members who grew up in the traditional system," she says, "that may be hard to accept." The Bologna process also calls on countries to strengthen -- or, in some cases, establish -agencies to assess the quality of educational programs. And there are efforts to establish European mechanisms for quality assurance. The aim is to make institutions and employers more confident about recognizing degrees issued by institutions in other countries. Maintaining Momentum Ultimately, say supporters, young people will be able to move from an institution in one European country to further studies or take a job in another as easily as, say, moving from New Hampshire to Texas. The Bologna process is the biggest shake-up of European higher education in years -- and the first time in European history that such educational harmony has been attempted. Yet officials worry the momentum could be lost if the reforms don't win the support of faculty members. Mr. Mettinger, the Vienna vice rector, says his biggest challenge is to persuade the university's various departments to "fill the [new degree] framework meaningfully, and think about outcomes and the needs of the labor market and lifelong learning. We have to convince people," he says, "that going to the Bologna architecture is not [just] a formal step, but a change of paradigm."