1 Bishops History Dept. Grade 10 Examination MEMO Time: Two

advertisement

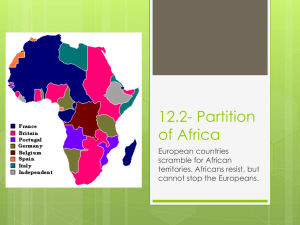

1 Bishops History Dept. Grade 10 Examination MEMO Time: Two hours 100 marks Wednesday, 4 June 2015 Examiner: Dr R. C. Warwick Instructions: 1. Section A (Source-based questions) is compulsory 2. Section B contains two essay questions; choose one of these. 3. Write neatly and plan your essays carefully within several separate paragraphs, including a short introduction and conclusion. 4. Good luck…. 2 SECTION A: Source A (1): The 2010 unveiling of Shaka’s statue at King Shaka International Airport in Durban; President Jacob Zuma and Zulu King Goodwill Zwelithini in front of the statue . 3 The same statue photographed further back – showing the cattle and Shaka Source A (2): 4 Source A (3): Explanation of the statue and later developments The Shaka statue was removed on 2 June 2010 because the Zulu Royal House (specifically the King) complained the statue made Shaka look more like a cattle herd boy than a king. The statue shows Shaka without a spear or shield and surrounded by cattle. The Inkatha Freedom Party, the main political opposition to the ANC government in Kwazulu-Natal (who strongly protect traditional Zulu culture but are also political opponents to the ANC) complained that the removal and design (and re-design) of the statue had incurred “wasteful expenditure” of tax-payers money. The Zulu King claimed the Zulu Royal House had not been properly consulted about the statue’s likeness. Construction of a new R3.2 million statue has apparently begun. The cattle statues’ depicted with the original Shaka statue still remain at the airport and the sculptor (Andries Botha) is demanding them returned, because his original work has been changed. R6.4 million has already been spent on the King Shaka Airport statue(s) sculpturing and removal, but according to news reports no new Shaka statue has yet been unveiled at the airport. In 2013 the (ANC) economic and tourism minister in the Kwazulu-Natal government announced that KwaZulu-Natal would have its own landmark superstructure - a towering statue of King Shaka holding an assegai - that will rival the Statue of Liberty, the Eiffel Tower and Christ the Redeemer in Rio de Janeiro. This statue will be in the region of 106 metres tall; but it is unclear what it would cost. Shaka’s life long pre-dated the invention of photography – there is no clarity at all as to Shaka’s actual likeness. (Summary of news developments on the Shaka statue as read off IOL.CO.ZA and NEWS24.COM) 5 Source B: Extract from Peter Becker’s 1964 book: Rule of Fear Whenever the Zulu army returned from an expedition it reported to Bulawayo (meaning Place of the Elephant -today an historical site in northern KwaZulu-Natal) to deliver the spoils of war and to await further instructions from Shaka……when the gathering was called to order….the tyrant rose and facing the throng immediately scrutinised the stabbing-spears, for by the number of spears held point-upward he was able to judge how many of his warriors had killed at least one of the enemy in battle. Returning to his throne Shaka called upon each of the Indunas (different regiment commanders) in turn to describe the battles recently fought and to bring both heroes and cowards before him. Shaka took pains to praise and reward all who had won distinction in battle, but he had cowards removed to the outskirts of Bulawayo, to Cowards Bush, to be impaled or clubbed to death.” * Peter Becker , Rule of Fear, Manchester, 1964, p.29. * Peter Becker was a white South African historian of African societies; fluent in Zulu and an expert in traditional Zulu customs and cultures. Becker was very close to and trusted by the Zulu King and Zulu politicians - strong links which remained thus all Becker’s life. Becker’s books were widely read by white South Africans interested in their country’s history and politics. During the 1960s Becker was considered without equal in his historical work on the Zulu people. But his descriptions were later challenged by new interpretations of the Mfecane. 6 Source C: Extract from Peter Becker’s book: Rule of Fear depicting the end of Shaka, murdered by his half-brother Dingane and associates. Dingane also went on to also establish himself (according to Becker) as a cruel tyrant. Dingane’s Zulu Army was defeated by the Afrikaner Voortrekkers at the battle of Blood River on 16 December 1838. Dingane was murdered in 1840 by his own Indunas (regimental commanders). A day or so later, on 22 September 1828, Dingane and Mhlangana (later joined by Mbopha), each arrived at Shaka’s kraal with a shortened stabbing spear concealed beneath a skin cloak…..The sun was setting as the three men waited. Although they could scarcely discern the tyrant’s shape….they could hear his voice….slating (abusing-shouting) that messengers had arrived late….At that moment Mbopha, an assegai (stabbing spear) in one hand and a knob-headed stick in the other….dashed into the open…Shaka rose to remonstrate with Mbopha, but then, as if struck by a thunderbolt, …jerked back on his stool and raised his voice in a piecing scream of agony as stabbing spears, thrust by Dingane and Mhlangana, plunged through his left-arm and deep in his back. Turning ponderously Shaka met the murdering gaze of his brothers with eyes screwed up in pain. “Children of my father”, he whined, “what is the matter”?.....with that Mbopha stepped forward and thrust an assegai into the King’s body. Frantic with pain Shaka struggled with difficulty on to an elbow and slowly fixed a haggard gaze on his assassins. “Mark my words,” he muttered huskily, “you will not rule for long. Soon this country will be overrun by white men”. And Shaka died.* * Becker used as source material for this account of Shaka’s murder, the Diary of Henry Francis Fynn – Fynn was an English settler and trader; one of the first white men to arrive in what is today Kwazulu-Natal; originally he was part of an expedition to set up an ivory trade with the Zulu and arrived in Durban Bay (today the lagoon which makes up the harbour) in May 1824. Fynn soon made contact with Shaka and learnt a great deal about Zulu customs and had contact with Shaka during several visits. Fynn’s trading expedition was by all accounts a success and later Natal became another British colony. 7 Source D: Shaka as a role model for 21st century businessmen Shaka’s name (has been) appropriated for commercial ends……by members of South Africa’s rising black middle classes. In 2000, lawyer and strategic consultant Phinda Madi published a motivational book for business people entitled Leadership Lessons from Shaka the Great. Amongst his injunctures (effectively his suggestions to business people to remedy any of their business difficulties): “To be a conqueror be apprenticed (be a learning assistant of) to a conqueror”; “Lead the charge from the front”; “Know the battlefield”; and, (with an eye to Shaka’s murder and downfall); “Never Believe your Public Relations personnel”. (Dingane and his brothers were Shaka’s close confidants – effectively advisors when Shaka was murdered). Source: http://www.sahumanities.org/ojs/index.php/SAH/article/viewFile/214/173 p.152 Source E: Shaka as one of the greatest men of all time “Shaka is universally acknowledged for creating and consolidating the Zulu as one of the most powerful and respected on the African continent and indeed on earth. His wisdom, leadership, strategic prowess, military genius and valour are legendary. In short it is difficult to imagine a handful of equals in history…..” Written by President Jacob Zuma in a forward to Phinda Madi’s book: Leadership Lessons from Shaka the Great. Source: http://www.sahumanities.org/ojs/index.php/SAH/article/viewFile/214/173 p.152 8 Questions: Section A. Source A (1, 2 and 3): (1) Studying the photos of Shaka’s statue, how do you think he has been depicted? Just a Zulu?....Zulu warrior/soldier? Herd Boy?...dignified depiction of a southern African pre-industrial black man of the 19th century?....patronizing* and kitsch#? Give reasons for your descriptions. /4/ * Treating something with apparent kindness but (the sculptor) betraying a superior attitude. # Bad taste – vulgar/offensive Marks according to a logical and consistent explanation fitting the description, as per a mark for a valid point…./4/ (2) King Goodwill Zwelithini attended the statue’s unveiling, then later criticized the statue and was instrumental in its removal. Give your own opinion as to how justified you think this decision was (and particularly the King’s role therein.) /4/ The boys need to think this through – perhaps Zwelithini felt disappointed the statue did not portray Shaka as a warrior and this “warrior” is central image of Zulu nationalism, which the King also represents. Clearly he changed his mind for a cultural depiction that was more aggressive because it suited his own constituency or even his own whims. It could also represent the political tension existent between the ANC government and the Zulu Royal House where the King feels the need to assert himself. Mark according to a reasoned, insightful argument, point by point. /4/ (3) The KwaZulu-Natal government have subsequently planned Source A (3) a huge Shaka statue but for a different site. Although nothing has yet transpired on this project, can you suggest a political reason why such an idea was put forward? /2/ The ANC run the provincial government and the organisation is increasingly Zulu-dominated with Zulu-speakers being the largest ethnic grouping in the country; announcing the creation and siting of such a huge Shaka statue is probably aimed at cornering remaining Zulu voters for the ANC. It is also an aggressive assertion of African nationalism which defines black politics in South Africa. Mark point by point trying to credit intelligent insight and logical thinking. /2/ (4) Do the Source A (1-3) serve as useful historical information – in other words, do they assist in enlightening us about Shaka’s life? Write a six line paragraph explaining your answer. /4/ Only very superficially do these sources tell us much about Shaka’s life; they portray a preindustrial era Zulu herdsman. But they say a great about how current traditional leaders and politicians would like to portray Shaka’s life - as a very powerful and aggressive figure of black leadership, and one which they want both Zulus and other SA cultures to know and respect (if not fear). There is clearly an attempt to place African Zulu culture and history symbolically on a level (African nationalists) assume other huge statues (Like the Statue of Liberty) accord Western culture – measured in grandiosity and the size of monuments (like the Voortrekker monument too). /4/ 9 Source B: (5) How is Shaka’s leadership portrayed in this extract: Stern; tyrannical; just; well balanced? Within a short (six line paragraph) chose one or more of these descriptions (or your own) to describe Shaka apparent attributes as a military leader. /4/ Perhaps in an African context of the day iShaka can be described as very strict but the awe and fear Shaka engendered was also tyrannical, certainly by pre-Mfecane African norms as we are led to understand. An insightful student will explain his answer with some contextual explanation including Peter Becker’s background and that his tyrannical portrayal of Shaka would have been realistic for his readers, and that the Zulu leaders back then no doubt wanted to emphasize to Becker that the Zulu King was one a formidable man. (Which might have meant something different to them as it does with the Zulu King and others today) Ascertain the intelligence behind the responses, awarding top marks only to those showing particular insight. /4/ (6) Peter Becker’s writings were based upon both written white missionary/settler sources (see footnote in source C) and the oral (history passed on by word of mouth from generation to generation) history he received via his close and trusted associations with the Zulu leadership of his time (1950s and 1960s). Discuss how verifiable (trustworthy, accurate, possible to prove) you believe such accounts can be. Write an eight line paragraph explaining your answer. /6/ Level 1: 1-2 marks; Level 2: 3-4 marks; Level 3: 5-6 marks. The white missionaries/settlers/traders wrote what they saw or were told about Shaka and obviously they wrote from their own perspectives and prejudices of the times. A good answer would note this but also that this does not completely invalidate these sources; Afro-centric historians and Zulu nationalists have also depended upon colonial sources. The boys should point out that because the Zulus of Shaka’s time were not literate and had no tangible means of recording experiences over time, there is remains a dependence upon colonial sources and to some extent archeological sources, leaving Zulu oral sources which are passed along and re-embellished to a point where reliability has to be questionable. A good answer will be able to sift some of the above points out well – leave “6” for an exceptional answer. Source C: (7) There seems little dispute that Shaka was murdered by his brother Dingane (even strongly Afrocentric historians accept this); Becker in fact concentrated more on describing Dingane’s history than he did Shaka’s. Could you suggest any reason why? /2/ No doubt because Dingane was also defeated in battle by the Afrikaner Voortrekkers and murdered by Zulus himself; Dingane has no victory mythology attached to him only the of a tyrant, murderer and loser. Shaka has all the other mythology and attributes of a leader connected to his person – and he never went to battle against whites. /2/ (8) Shaka’s dying words, according to Becker who may well have been using poetic licence (his own imagined descriptions) were prophetic (foretold the future), particularly as Becker was writing in 1964. Do you agree? /4/ 10 Yes, because the Zulu were to be defeated by both Afrikaners and the British; Natal became a British colony. Again Becker was writing for a white South African audience in the 1960s who would have been affirmed by Shaka’s supposed “prophecy”. Becker could not have foretold that Shaka would make such a big cultural and nationalistic return long after the 1960s. Some students might also argue Shaka was wrong as Zulu nationalism is again a very powerful force in the country today and build on that kind of argument. /4/ Source D: (9) Phinda Madi’s book is intended for a very different historical context than the Zulu Kingdom of the early 19th century. Do you see any link between 21st century business practices and the points Madi makes (underlined in the source…) Refer to historical points before commenting on a “business” point. /6/ Level 1: 1-2 marks; Level 2: 3-4 marks; Level 3: 5-6 marks. “To be a conqueror be apprenticed” Shaka did “work his way up the ranks – often by murder- but Madi makes a relevant point, as with (be a learning assistant of) to a conqueror”; “Lead the charge from the front”; “Know the battlefield” – this fits all the mythology about Shaka as the inspiration behind new weapons and battle tactics; and, (with an eye to Shaka’s murder and downfall); “Never Believe your Public Relations personnel” In the corporate people will try to “knife each other in the back” to achieve the top positions, although this might at first appear a comical part of Madi’s advice – it is probably the most accurate connection between Shaka’s life and the corporate business world. Some might say Madi was just being opportunistic and build a negative argument of his book thereon. Keep 6 marks for the exceptional, original arguments. (10) Why do you think Madi did not choose Dingane as his business model? /2/ Dingane never showed any “profit” – not a state builder or a successful general, his rule was tyrannical and he was defeated in battle by whites and he murdered Shaka. Zulu nationalists and the ANC government say very little about Dingane – many businessmen would not even have heard of him; he work not work as a good “brand” in corporate jargon. Source E: (11) Referring to this source and its author, give your opinion how justified you believe President Zuma is in making this statement about Shaka. Refer to all sources in making your assessment. /12/ 11 This should produce some interesting arguments given Zuma current very bad press; some guys might scorn Shaka being compared to Napoleon or one of the great world leaders; others might suggest Shaka is a great man in an African context and this need be understood; some might dismiss Zuma’s statement as Zulu-partisan and ignorant – based on their current perceptions of him. Some might be very defensive of Zuma and Shaka. There should in all essays be reference back to the sources and a well-reasoned, original argument in order to attain top marks. Level 1: 1-5 Unexceptional to mediocre use of sources, little or no real interpretation; weak to unimpressive understanding. Level 2: 6-7 Average use of sources; stock, predictable interpretation thereof; average understanding. Level 3: 8-9 Good use of sources; good interpretation thereof; intelligent understanding. Level 4: 10-12 Excellent use of sources; original interpretation thereof; sophisticated understanding. Total Section A: 50 marks Section B: Choose either Essay 1 or Essay 2 Essay 1: Historians long before the times of Peter Becker and his followers were aware of the Mfecane as a major historical process of upheaval within black African societies during the early nineteenth century. During the 1970s and 1980s, additional explanations for the Mfecane were produced by southern African historians. Write an essay discussing in detail the different explanations of the Mfecane and what lay behind their interpretations. Include in your essay at least one long paragraph explaining whether you think 12 the Mfecane should (or should not) be given a prominent place in South African schools history syllabi and why you reason as such. /50/ Historians are divided about the causes of the Mfecane; Marxist 1980s interpretations compete with older ideas of Shaka and the Zulu being the sole Mfecane initiator. Marxist interpretations identify Europeans at the Cape and Delagoa Bay as being catalysts of the Mfecane, not population and environmental factors. What is not disputed is that the Mfecane reshaped the political landscape of South Africa in terms of the tribal patterning of African societies. But although the Mfecane might have started earlier than the nineteenth century, historians are divided as to the extent of Europeans being the initiators. From around 1780, in the territory from Delagoa Bay to the Tugela, African chiefdoms began to grow in size and power; weaker communities were dominated or expelled; effects even touched the Pedi inland. This led chiefdoms further inland to strengthen their military capabilities; some chiefdoms caught up in this growing conflict fled, split or merged with others. After 1810, Dingiswayo of the Mthethwe surrounded himself with allies and forced those who refused to join him into tributary status – one of these was the Zulu whom after a chief’s death, Dingeswayo appointed Shaka as leader. Shaka worked his way into being King of the Zulu from this point amidst conflict amongst different chiefdoms. The disruption was widespread and also affected Tswana kingdoms. In the 1960s, Historians also argued that over-population due to the availability of secure food sources (particularly maize), or the effect of climate change such as drought and long-term environmental degradation may have caused competition for grazing land. Peter Becker wrote his early 1960s history of Shaka/Dingane/Zulus during a time of white South African rule and apartheid effectively represented the complete defeat of blacks in South Africa; so his history was meant for this audience who then were able to affirm themselves and reendorse perceptions of black savagery, tyrants, suspicious/hostile to whites and an inability to modernise or be equal citizens in a modern state. The Mfecane was closely connected to this view of Shaka as a tyrant. Shaka’s Zulus attacked others setting up a domino process which swept across southern Africa and this devastated the African population, creating an “empty land” for white occupation – these were the wars of Shaka. Therefore, according to such older theories including Imperial and Afrikaner nationalist, the Mfecane process scattered black Africans and opened up areas in Kwazulu-Natal and the north where British settlers and Afrikaner Voortrekkers moved in. There could be no charge of white appropriation of “empty land” because white settlers and Boers moved in where blacks had left. From late 1960s/early 1980s, this idea of the Mfecane was criticised. Afro-centric, Africanist and Liberal historians now wanted craft a more positive historical portrayal of African societies; one historian in particular, Omar-Cooper, spoke about it also being a time of creation and the emergence of African kingdoms – this asserted positive aspects. These historians wanted to show Africans had reacted rationally to new developments and that the Mfecane was a period of statebuilding by innovative chiefs, rather than slaughter and tyrant-led confusion (Shaka) seized upon by Apartheid apologists to justify the “myth of the empty land”. So there were great African statesmen like Shaka, Moshweshwe of the Basotho, Mzilikazi of the Matebele who were nation- 13 builders determined to protect their people from colonisation and Afrikaner Voortrekkers. Curiously Shaka made a popular “comeback” in South Africa during the 1980s with an SABC-TV series Shaka Zulu. Another group of historians from the 1980s, prompted by the Marxist-based writings of Julian Cobbing stated there had been no Mfecane rather it was an alibi to cover white occupation – a myth to justify colonial settlement and white rule. Cobbing’s Mfecane thesis was predominately based on the idea that the Mfecane as a process in itself was an event that just did not occur – not that there were no disruptions in African societies during the early 19th century, but that the term Mfecane misleads back to older (for Cobbing) discredited histories. For Cobbing and those following his arguments, the term Mfecane had been so misused by historians whose motives and attitudes he distrusted that in his opinion it should be disused altogether. The entry of new trade goods into southern Africa created black competition and the need to wield sufficient power to control access to this trade. European demands for ivory and gold may have been the reason for Nguni militarisation and reorganisation of their economies. Cobbing referred to negative effects upon African society from both Portuguese slave traders in Delagoa Bay over a long period and Dutch/British colonization as having disrupted/damaged the settled existence of southern African societies. Out of this Shaka and the Zulu were reacting in a defensive manner as were other African societies/newly formed nations/tribes in trying to bolster their people at a time when future coming changes could be catastrophic. Cobbing was suggesting that the older theories of white historians describing Shaka as a tyrant and the Zulu as aggressive and warlike needed to be completely refuted because so strongly imprinted in popular understanding that blacks were “savage”. For Cobbing the central catalyst of upsets in early 19th century African societies was principally European invasion/exploitation. Later in the 1980s, early 1990s there was a kind of Mfecane again with ANC and IFP Zulus at war with one another, resulting in by far the highest casualties by region and race during this period. How relevant is the study of the Mfecane to South African History and our contemporary society? There is little doubt the Mfecane left a strong tribal legacy which remains embedded in South African politics and society. That in the popular mind Shaka looms largest out of all leaders, black and white of that time. The Mfecane must have a place in SA history just for these factors alone, but historians need be cautious in how they employ the theorizing today, because the above theories too have to be seen against the context of the various historians and who they wrote for. The Mfecane is not the central story of the growth of modern South Africa, so it is contestable whether Shaka can be considered a central (great) figure of SA history. And finally, some guys might want to comment on contemporary Zulu nationalism – the King’s apparent outburst against foreign Africans; attempts by the ANC government to placate him; last year’s parliamentary scenes centred around Jacob Zuma and Nkandla. Is there a future for Zulu nationalism in a South Africa supposedly striving to be inclusive and non-racial? Or is Zulu nationalism/and/or African nationalism the future? Has Shaka just been revived more as a commercial entity and “brand” – like Shakaland and his statues are sort of bill boards for spreading this “brand”, wherever or however it is utilised? 14 Essay 2: The British Colonisation of southern Africa receives a bad review today from several political positions, yet it is impossible to envisage South Africa as we know it today without direct British involvement stretching over more than a century. The first part of the nineteenth century was a time of British Imperial conquering and modernisation; discuss how British Imperialism, governance and settlers, affected Afrikaners, Xhosa, and Khoisan/San negatively, while also commenting on positive British contributions. Include in your essay one long paragraph discussing whether on balance, British involvement in South African history was for the better or worse. /50/ The frontier theory - of it being “Open” or “Closed” was according to whether official and comprehensive colonial/settler control was established or not in the area under consideration: The Cape. Under the Dutch this was a huge area with a vast frontier they were attempting to ‘close’; exceedingly difficult particularly as it contained both arid country and well watered grasslands where colonists could easily be a law unto themselves and Khoisan and Xhosa could exist within their own cultural milieu (cultural settings). But for colonial officialdom there were extremely limited communications dependent upon pre-industrial modes of transport such as horses/oxwagons transport. The ‘Boers’ were the descendants of Dutch, German and French groupings of seventeenth/eighteenth century colonists whose lingo franca (common language) developed into a local variety of Dutch – much later identified as Afrikaans; they distinguishing themselves as ‘African’ – Christian, but not loyal to Holland let alone Britain. An example well used in Afrikaner nationalist historiography was the Slagtersnek Rebellion. The “Afrikaner” Trekboers were small scale farmers who had been moving (trekking) across the colony since early Dutch rule. GraaffReinet was the site of the first magistrate established outside of Cape Town during Dutch East Indies Company (VOC) rule – an attempt to ‘close’ the frontier by policing outlying colonists. After their defeat of the Dutch colonists in the western Cape at the 1806 battle of Blouberg the new British administrators/military/colonists who had arrived specifically to secure Cape Town for strategic reasons during the Napoleonic wars, tried to enforce a more efficient colonial administration over the entire colony than that very ineffective control achieved by the VOC. The Khoi tribes started already breaking down during earlier eighteenth century Dutch rule; mainly due to a smallpox epidemic in the western Cape, but also to enslavement for some and the scattering of the rest into the interior. But by the mid-nineteenth century, Khoi and Khoisan tribal structures were effectively finished. The remnant Khoisan peoples in time were physically and biologically integrated with some colonists and the numerous slaves brought by slave traders during the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries from Africa (Madagascar, Angola particularly) and Dutch Indonesia. These imported slaves had been sold to both Boer and British colonists in Cape Town and to farms within the western, northern and eastern Cape. 15 Some Khoi tribes had also integrated into the Xhosa chiefdoms. The San suffered a similar fate of cultural disintegration though for some it was delayed for their hunter lifestyle enabled these to live in the mountain ranges from where they were ultimately hunted out or enslaved by colonists, assisted by their Khoi slaves/servants. The San fled even deeper until the last surviving San groupings remained north of the Orange River. The new British administration and particularly early Governor Lord Charles Somerset attempted to exert additional control and ‘close’ of the colony’s frontier; the most difficult section of which was the eastern Cape (Eastern Frontier) where Boers and the vastly more numerous Xhosa had already long clashed over land – both groupings being cattle farmers. Unlike the Khoi, the Xhosa had numbers and physical robustness on their side. Although the Xhosa did not form any politically centralised grouping they existed within several large chiefdoms which sometimes combined in times of war but also clashed with one another and even on occasion, allied with colonist/settler forces. The placing by British officials of limitations upon the Boers backed by law, reinforced by regular British Army soldiers and far more courts was resented by many of the Boers, particularly those less successful in farming. The British determination to ‘close’ the frontier was feared by the Xhosa who during the early nineteenth century Frontier Wars came to realise that the British had significant military resources and when black/white fighting broke out, almost always combined with the Boers against the Xhosa. Several vain attempts were made by British administrators to separate black and white usage of grazing land by establishing “frontiers” or “borders” marked by rivers or “no man’s land” concepts. In the end these were a failure and the Xhosa chiefdoms were pushed further back towards the Kei River. Supposedly agreed boundaries were inevitably ignored during trading, hunting and particularly cattle raids or attempts to regain stock. The land disputes and lack of resolution therefore added to already existent suspicions and negative perceptions of respective cultures which existed between white and black and between the white communities too. The Boers viewed British administration of the frontier as unsympathetic to their lifestyles and needs – particularly British lack of legal grounding or sympathy for an explicit slavery culture. The Boers blamed the British authority and missionary work for the instability of the Eastern Frontier. But arriving British settlers also found themselves in the midst of the frontier wars; Grahamstown originally founded in 1812 as a British military outpost, later became a beleaguered garrison town where 1820 settlers who had failed with farming, moved to establish themselves in more secure trades. A glance across maps of the historical Eastern Cape indicates the extent to which British influence permeated through place names. But the impact was also commercial besides private and state education, law, culture and resolute administration with the resources of a then growing and vast empire. There are many theories for the Xhosa “Cattle-killing” of the early nineteenth century on why this occurred; most of which are closely related to Xhosa belief-systems of the time and their despair at the seemingly unending and unwinnable battles against the white colonists – more so now the British. But whatever the causes and complexities in explaining the “Cattle-killings”; the results for the Xhosa were catastrophic and hastened the political disintegration of their society. There were many further frontier wars until the complete defeat of the Xhosa by the end of the 19th century. 16 Mission stations were set up by amongst other church groupings, the London Missionary Society, which took particularly a more Christ-centred interpretation of Christianity rather than the heavily judgemental Old Testament teachings which the Boers understood through their Reformed Church theology. The mission stations were intended to try and both convert the Khoi and Xhosa and also supposedly teach them the understanding of a Christianity-approved work ethic. But missionaries like John Phillip and Johan Van der Kemp were also appalled at the very harsh slave owner/slave relations in the colony and were very unpopular with the Boers who viewed them as naïve and accused them of usurping “proper black-white relations”. By 1838 slaves were emancipated (freed) throughout the British Empire, although many remained servants under slave-like circumstances. But the most conservative and resentful of Boer society by now had rejected both this liberal approach and the British administration of the colony. Hence parties of Boers from this year “immigrating” north to move away from both British control and Xhosa attacks – the so-called “Great Trek” which became a core part of Afrikaner nationalist historical explanations following a ‘heroic’ theme of a ‘people’ moving to establish their own selfdetermination from oppressors and violent indigenous groupings. The Cape Colony early to mid- nineteenth century society was stratified along racial lines in terms of property and ownership. Nevertheless there were still many “mixed-marriages” with the husband usually white and some “coloured” families prospered to an extent. Increasingly towards the middle of the century many coloured and Malay communities believed in and valued British Imperial “citizenship” particularly amongst those in Cape Town. But race relations between master and servants could still be exceptionally harsh, a situation which by and large the law still supported. But the colony’s administration being British meant that it viewed the Cape colonial role through British interests first, not least concerns of paying for the frontier wars. One of Somerset policies was trying to create a ‘buffer zone’ between colonists and Xhosa using new British settlers – those of 1820; some 3000 strong, to farm in the Albany (Grahamstown) district. Note that the Cape at this stage was still a backwater colony; far more British and Irish settlers went to America and Australia; the former by 1820 was already the United States. The Cape was certainly nowhere near industrialised – this only really started in the late-nineteenth, early twentieth centuries along with the diamond/gold discoveries and associated European immigration. But these 1820 British settlers and the trickle of British immigrants which followed did bring some farming improvements – merino sheep for example, besides other important cultural contributions. Cape Town and Simon’s Town remained important strategic harbours; Port Elizabeth grew, but British settlement outside of the Eastern Cape’s brief concentrated influx of 1820 was still comparatively small compared to say the Canadian, Australian and even New Zealand colonies. Some of most important cultural features which the British brought to the Cape during the early part of the nineteenth century were the beginnings of formal education. SACS was the first formal state school – 1829; intended to get British and Dutch settlers sons to know each other along ‘British cultural lines’; some English businessmen like Charles Adderley became prominent in Cape Town; British settlers Thomas Pringle and John Fairbairn fought Governor Somerset through the colony’s law courts to insist on a free press for the colony. By the 1840s the Church of England felt there was enough of a British presence to send out Bishop Robert Gray to establish a separate 17 province of the Anglican Church in the Cape; as we know, Gray not only did that but also established several church schools including Bishops. Very importantly, the British brought the first framework of liberal democratic government on a qualified voting franchise to the Cape; by 1872 the first Cape Parliament existed on this non-racial qualified vote. The Eastern Cape frontier wars went on until the end of the nineteenth century and were exceedingly bitter on both sides; the ramifications of which live with us today. These were effectively wars over land which the colonists - British and Afrikaner; ultimately won comprehensively; “subduing” the Xhosa. The British by then were trying to govern the Cape along with the British settlers over the growing “Cape coloured” population, the still vastly numerous Xhosa and the many remaining Afrikaners, some of whom had become prosperous and an influential few even anglicised. British colonial administrators feared further regional instability would negatively impact upon the ape Colony. Their main concern was with the long-departed “Great Trek” Afrikaners now within the two Boer Republics in the north, the Orange Free State and Transvaal and their continuing land wars with their black African neighbours. The tribal groupings formed by the Mfecane resisted the new immigrants from the south as the Eastern Frontier conflict was “exported” north and east. Some of historian Niall Ferguson’s theories (his “Six Killer Applications”) fit fairly well into the Cape’s nineteenth century history. Most particularly that the British were more effective than the Dutch in “closing the frontier”: Establishing and enforcing European law on the colony; not least property rights and then ultimately linking these on a non-racial basis (although still predominantly European) for voting towards a legislature (parliament). The language of the law and its structure/culture would be both British and Dutch – Roman Dutch and English Common Law. But it meant that within the slowly modernising colony, black and ‘coloured’ subjects were now being subordinated to this new ‘western’ culture and its slowly growing capitalist economy. Later black elites during the early twentieth century would express their aspirations through the religious, political and language culture of the British Empire: The South African Native National Congress of 1912, forerunner to the present day ANC where those of Xhosa origin were to play a leading role: Mandela and Mbeki being the best known. Check for a reasoned paragraph accessing British involvement in the Cape Colony up to 1850. Total Section B: 50 marks 18 *********************************************