Dillon`s rule holds that local governments are “creatures of the state

advertisement

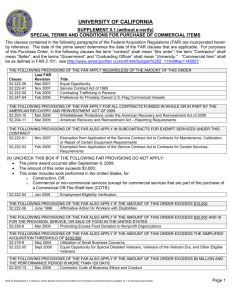

The Role of Direct Democracy Within Nested Municipal Institutions Barbara Coyle McCabe School of Public Affairs Arizona State University barbara.mccabe@asu.edu & Richard C. Feiock Askew School of Public Administration and Policy Florida State University www.fsu.edu/~spap/feiock rfeiock@coss.fsu.edu Paper presented at Midwest Political Science Association Annual Meeting, Chicago April 3-6 2003. Paul Lewis, Max Neiman, George Fredrickson and Robert Stein provided helpful comments on earlier versions. We gratefully acknowledge the generous support for this research project provided by a grant from the Lincoln Institute for Land Policy. Introduction Like constitutions, city charter provisions structure the incentives of political actors and determine the kinds of decisions that will (or will not) be rewarded (Myerson 1995). As a result, different formal governance arrangements are expected to lead to different policy outcomes. In this paper a contractual approach is applied to local political institutions (Maser 1998). Treating local institutions as a constitutional contract allows us identify the potential consequences for local government tax, spending and borrowing decisions that arise from provisions for direct democracy. Our conceptual framework bridges competing models prevalent in the local public finance literature. Empirical tests of several propositions regarding fiscal policy in large cities between 1980 and 1996 are derived from the framework. The analysis provides preliminary evidence to support these propositions. Nested Institutions The new institutionalism in economics and political science identifies hierarchies among types of rules, with the resulting levels of action categorized according to their affect (Ostrom 1990, 1994; Brennan and Buchanan 1980, 1985). Constitutional-level rules establish the overall rules of the game and lay out the basic system of governance. Substantive rules deal with a specific policy area such as the environment or taxation. Ostrom describes this hierarchy as “nested,” evoking the image of lower level, substantive rules imbedded in a framework of higher-level constitutional rules. Each of these levels of rules and actions is described below, with examples keyed to their use in this study. 1 Constitutional-level rules delineate the framework for legitimate action, including the procedures for formulating other rules and policy for aggregating choices (Brennan and Buchanan 1980, 1985; Ostrom 1990). Form of government provisions (such as separation of executive and legislative powers), electoral scheme (such as district or atlarge elections) and provisions for direct democracy (such as referendum requirements or the allowance of citizen ’s initiatives) are examples of constitutional level rules. Because institutions are nested, specific policy outcomes will depend, not only on the provisions of the substantive rules, but also on the opportunities and constraints created in the constitutional-level rules. Hansen (1983), for example, found provisions for citizen initiative to be the single factor that distinguished states in which legislatures had adopted tax and spending limitations from those that in which they had not. Hansen’s findings suggest that the likelihood of passing a state tax limit depended on the presence of a constitutional rule, not just on conditions in the environment such as the tax burden. Similarly, using data from opinion polls, Gerber (1996) found that states with referendum provisions adopted policies that were more in line with median voter preferences than states without such constitutional-level rules. In both cases, the mere presence of the rule--not necessarily its use--was sufficient to make the difference in policy choices. Cities differ in their choices of constitutional as well as substantive rules. Dillon’s rule holds that local governments are “creatures of the state” and can only undertake activities the state specifically authorizes. Nearly all states, however, have made provisions for municipal home rule. Home rule cities enact charters that establish 2 governance structures and rules of governance. Charters may also broaden municipal powers beyond those expressly granted by the state (Krane, Rigos and Hill 2001). City charters express constitutional-level rules that define the citizens’ rights to have their preferences included in the process of public decision making (Maser 1985, 1998; Miller 1985). State rules may provide options for forms of municipal government, but the selection of local governance institutions is primarily a local choice. Transaction Resource Theory Whether in agreements between individuals or in constitutions, parties to a contract agree to cooperate because the potential gains of cooperating are greater than the status quo. The potential alone is not enough. Potential parties to a contract face problems of coordination, when they can misconstrue the efficiency gains that can be realized by cooperating. The parties also face division problems regarding the allocation of costs and benefits. Finally, parties to a contract bear the risk of defection, when individuals opt out of the contract for their personal gains at the expense of collective benefits (Coleman, Heckathorn and Maser 1989). In simple, small-scale transactions, information can be gathered about whether coordination will create joint benefits. Division problems can be resolved through faceto-face negotiating, and defection can be detected through monitoring. As more issues and more parties become subject to the potential contract, the transaction costs of mitigating these risks rise, and uncertainty increases. Transaction resource theory posits that, in these more complex situations, individuals create governance organizations, provided with powers and constraints, to act as third party intervenors as a means of 3 securing the benefits of cooperation. Governance organizations can provide information services (regarding, for example, water quality) to clarify potential benefits from coordination. They can provide division services to distribute the gains from cooperation, or they can provide enforcement services to address the risk of defection (Maser 1998). Essentially, government becomes "a central party common to all contracts" (Heckathorn and Maser 1987, 164). These contracts are necessarily incomplete in that they cannot foresee specific future problems of cooperation, division or defection. Instead, they establish procedures for how these problems can be resolved. In this way, these relational contracts perform one of the most important functions of institutions: reducing uncertainty. When local government functions as a third party in a relational contract among citizens, constraints on governmental authority are necessary to resolve problems of coordination, division and defection. The constitutional provisions of municipal charters enhance cooperation among citizens in a community by defining the obligations, rewards, and penalties imposed on contracting parties. Provisions for direct democracy can be central to the relational contract among citizens because they impose constraints on government that function as a mechanism to overcome barriers to collectively beneficial actions among citizens and mitigate the three major risks to cooperation (Heckathorn and Maser 1987; Maser 1998). The risk of incoordination creates a demand for rules to promote stability and decisiveness in governance. The risk of inequitable divisions creates a demand for rules to promote responsiveness, defined here in terms of the preferences of the median voter. And the risk of defection gives rise to the demand for rules to promote efficiency.” (Maser 1998: 541). 4 The charter provides constitutional rules to reconcile coordination, division, and defection. Coordination problems arise if the parties can misconstrue the feasibility of cooperating and risk missing out on efficiency gains. Rules that promote stability in resolving controversies and enforcing the contract facilitate cooperation. Procedures that increase stability decrease the ability for parties to change the rules for each new cooperation problem or to undo prior agreements. The second barrier to cooperation, division problems, arises when preferences conflict. Division problems are especially difficult to anticipate because preferences are not fixed. Resolving division problems requires negotiation in order to arrive at a fair and equitable allocation of the benefits and costs of joint action (Heckathorn and Maser 1987). Here, local government becomes the arbitrating third party that is granted the authority to allocate cooperation gains or to narrow the division range. The final barrier to cooperation, defection, is most directly linked to efficiency. When government becomes the third party intervenor, defection problems occur when elected or appointed government officials engage in individually rational, opportunistic behavior at the expense of the citizenry. The notion of government as Leviathan is an extreme example of government that exploits the governed for its own purposes. Defection also includes a host of more mundane principle-agent problems such as officials' not holding firm to their campaign promises or bureaucrats withholding information that would facilitate an accurate assessment of their accomplishments. If elected officials credibly committed to a policy rule, the problem of moral hazard would be diminished. Opportunistic behavior results from freedom for ex post action (Dixit 5 1996). Opportunistic behavior also arises because contracts are either incomplete or contain loopholes that can be exploited to an individual's benefit (Milgrom and Roberts 1992). Defection problems can be eased by measures intended to promote efficiency that keep public policies in line with public preferences. Cities confront each of these coordination barriers in making fiscal choices. Decisions about the levels and types of revenues extracted from the population pose three separate coordination problems. What will work? What means are fair (or, at least, which individuals should pay)? And what assures the governors' compliance with the citizens' preferences? Constitutional-level rules, exogenous to each city’s annual fiscal decisions, delineate how decisions can be made. Rules for direct democracy grant city residents a voice in making these choices. Local Direct Democracy Direct democracy transfers legislative power directly to the people in an effort to ensure that public policy is not inconsistent with the popular will. Each mechanism for direct democracy offers different opportunities for direct citizen action. The initiative allows voters to propose a legislative measure or constitutional amendment by filing a petition bearing the required number of signatures. The referendum refers an existing or proposed law to a popular vote. The recall allows voters to remove an official from office by filing a petition demanding a vote on the officials continued tenure in office (Cronin, 1989). In delineating the contractual implications of local government institutions we borrow extensively from the work of Steven Maser (1995; 1998). Maser 6 uses provisions for direct democracy as examples of rules to address each of the three contracting problems discussed above. Provision of the initiative provides a constitutional safeguard to address the risk of “incoordination” (Maser, 1998, p. 541). Coordination failures occur when government rejects outcomes preferred by the median voter or accepts outcomes that the median voter dislikes. Certain rules enhance predictability and stability by restricting the set of possible outcomes. Separation of powers, checks and balances and supermajority requirements all address coordination risks and promote stability. Likewise ballot initiatives may reduce coordination problems for local polities and enhance policy stability by empowering the citizens to place a measure on the ballot when legislators have not acted. Initiatives have to be accepted or rejected on a majority vote, which limits the problem of issue cycling (Riker 1982) and heightens coordination. Furthermore, since the median voters’ preferences are most apt to win, those that draft the initiative measure are unlikely to deviate from their idea of the median voters preferences (Maser, 1998: 546). When this logic is applied to local government fiscal choices it suggests that initiatives should promote stability. Nevertheless, if the median voters preference for pubic goods is greater than the status quo, initiatives may result in higher levels of taxation, spending, and debt by encouraging voters to reveal preferences honestly. Similar to an assurance game, people who are willing to pay more for public goods are not bound to do so as a consequence of revealing their preference. Nonetheless, the 7 absolute value of the change in revenues or expenditures, rather than the direction of the change, is an indicator of fiscal stability. Different kinds of issues are typically resolved through different kinds of processes. Distributional issues are among those most often addressed through initiatives. Efficiency (i.e. “good government” issues) are more often settled through the legislative process (Matsusaka 1992). Policy outcomes that differ because of rules providing for initiatives (and other measures of direct democracy) may be expected to be found in cities’ decisions to tax and spend. If initiatives promote stability and reduce the likelihood of opportunistic behavior among elected officials, we would expect greater stability in spending in initiative than non-initiative cities. A referendum mitigates the risk of division failure by granting citizens the right to call a pubic vote after officials have acted. For example, elected officials, intent on reelection, may behave opportunistically by advocating spending on bricks and mortar projects supported by public debt that provide visible evidence of their actions in office to reward their supporters (Feiock and Clingermayer 1992). Referenda provisions may constrain such patterns of behavior. Uncertainty enables Leviathan to reap greater revenue yields, and external controls such as referendums curb uncertainty (Brennan and Buchanan 1980). To the extent that higher levels of local taxing, spending, and borrowing result from opportunistic behaviors of public decision makers and uncertainty, the presence of the referendum would be expected to result in less tax, spending, and debt. 8 Recall provisions mitigate the risk of defection by granting citizens the rights to strip elected officials of their authority to act. Defection provisions are intended to hold actors accountable in order to ward off inefficient, opportunistic behavior (Maser 1998: 544). Recall provisions cannot eliminate moral hazard, but they do provide a mechanism for addressing defection once it is discovered. If recall provisions promote efficient behavior, the revenue systems of cities with recall provisions should rely more fully on efficient, market-like revenue extraction devices than in cities without recall provisions. This prediction is consistent with Matususaka’s finding at the state level that states with provisions for direct democracy rely more on fees than taxes. Fees, like prices in the market, act as a direct signal of consumer preferences, and the ability to charge beneficiaries the costs of services has been described as a near guarantee of efficiency (Ostrom, Warren and Tiebout 1961) With taxes, decisions about rates and expenditures are made by elected and appointed officials. These officials suffer from limited information in attempting to be responsive to voters because they must estimate voters’ preferences for taxing and spending. Even without opportunistic behavior, revenue systems that rely more on taxes than fees are less efficient because the revenue devices are not automatic measures of actual consumer preferences. The fact that cities must provide public goods means that the revenue composition cannot be completely fee-based (Musgrave and Musgrave, 1976). But cities can depend on these revenue sources to differing degrees. We would expect, however, that cities with recall provisions draw a greater proportion of their revenues from fees and charges than other cities. 9 We anticipate that the simple presence of rules for direct democracy—even if they are infrequently used—mitigate elected officials’ opportunistic behavior that deviates from constituents’ preferences (Matsusaka 1995; Gerber 1996) Local Fiscal Behavior and Models of Government How might a contractual approach to local governance be applied to the empirical study of local fiscal choices? First, it may provide further evidence that within a democratic polity fundamental differences in constitutional rules lead to different substantive outcomes, a finding that may have great practical value in the search for efficient institutional choices. Second, the contractual approach may provide a conceptual link to help reconcile competing theories of fiscal choices that have guided empirical study. Two competing models have dominated the study of local government fiscal behavior: a median-voter/benevolent dictator model and a Leviathan/budget maximizing bureaucratic model (Shapiro and Sonstelie 1982). Both share the assumption that local officials are self-interested. Under the first model, however, local officials, intent on reelection, seek to maximize the community-wide benefits of fiscal policy choices by making decisions that are consistent with the preferences of the median voter. The median voter model assumes that local politics work to constrain local taxation and spending, because voters hold elected officials accountable for their fiscal choices. Officials whose tax and spending decisions are far from those of the median voter will be ousted from office, and replaced with officials whose decisions are closer to the median 10 voter preferences (Chicoine, Walzer and Deller 1989). Efficiencies are realized as potential residents choose among competing cities, selecting the one with the tax and service package that best meets their preferences (Tiebout 1956). Municipal power to zone land means that city officials can control the density and intensity of future development to assure that new development will add to, or at least not subtract from, the local tax base (Hamilton 1975). With Tiebout sorting, the property tax may serve as an efficient benefit tax, since the cities’ elected officials make decisions about both property taxes and land use (Fischel 2000). Where these assumptions are met tax and expenditure levels already reflect the preference of the median voter. The Leviathan model, on the other hand, describes a government driven to maximize its tax “take” by exploiting its citizens (Oates 1985). In this model, selfinterested officials are strategic actors that use the power of the purse for personal gain, suggesting that agency failure is the norm. Since the forces that compel politicians and bureaucrats to maximize revenues are intrinsic to politics, exogenous rules are needed to limit taxing and spending (Brennan and Buchanan 1980). The tax and expenditure limits (TELs) that states impose on cities are an example of such a rule. Empirical findings that TELs are effective in reducing revenues or expenditures have been cited as prima facia evidence of Leviathan government (McGuire 1999). The median voter and the Leviathan models speak to the importance of politics in decisions to tax or spend. Ironically, each ignores differences in political institutions among cities, and assumes that local governments behave monolithically, as either fiscally-restrained, median-voter-pleasers or as a tax-maximizing, citizen-exploiters. 11 Similarly, Tiebout’s (1956) model assumes local decision makers are apolitical, and that the tax and service packages they offer are intended to “attract enough residents to stay solvent” (Fischel 2000, p. 9). Perhaps because of the focus on residents shopping among communities, tests of the Tiebout model have tended to address the demand side, leaving the supply side of the model, which would tackle political distinctions among local governments, less fully developed (Fischel 2000). Despite recognizing distinctions in the nature of higher-level rules and in the factors of demand, the models ignore institutional variations in governance among cities. Local constitutional-level rules for direct democracy may function much like stateimposed rules—as an exogenous constraint to keep local tax and spending decisions closer to the preferences of the median voter by promoting stability and efficiency in fiscal choices. In addition, the constitutional choice of municipal government form would be expected to create incentives that differ in terms of the behaviors that are rewarded, and in terms of the incentives’ power to prompt opportunistic behavior. Building upon the work of Oliver Williamson (1981; 1999) Frant (1996) argues that council manager governments replace high-powered incentives with low powered incentives. High-powered incentives result from market or market-like transactions, and are powerful because the benefits from the transaction are directly realized by its parties. In markets, high-powered incentives lead to efficiencies in allocation. However, when politics substitute for markets as the medium for exchange, high-powered incentives may fail to promote production efficiencies that lead to cost reductions; instead they lead to political opportunism (Frant 1996). 12 Using Maser’s (1998) terminology, institutional provisions in local charters may address division problems. The proposition that council-manager government insulates governing from “private regarding” demands (see Banfield and Wilson 1963, Lineberry and Fowler 1967, and Morgan and Pellisero 1980) suggests that division problems were one of the key rationales for that form of government. The credible constraint of morally hazardous behavior is fundamental to the efficiency of public organizations (Miller 2000). We expect that the Leviathan model is more likely to be operative in cities operating under charters which provide for mayorcouncil government form and lack provisions for direct democracy. Local politicians in those cities are able to reap the political benefits of their decisions to tax and spend without the threat of direct citizen action. We expect fiscal policy choices to be more closely linked to median voter preferences where local charters provide for council manager government and provisions for direct democracy. We test these proposition by examining the revenue choices of large US cities from 1980-1996 in light of their provisions for direct democracy, form of government and demand for services. Approach We test a simple model to evaluate the effects of local institutions on cities’ revenue choices, using pooled cross sectional time series data. Observations are included for each year from 1981 to 1996 for a panel of U.S. cities with 1989 populations of at least 75,000 that are central cities of an MSA. The two dependent variables examined here are per capita own source revenues collected from citizens in the community and the proportion of own-source city revenues derived from fees and charges. As 13 constitutional-level rules, the model includes form of government and the three measures of direct democracy, initiative, referendum and recall. Per-capita personal income provides and indicator of the fiscal presences residents. Our analysis also controls for other characteristics of communities that can influence policy preferences including population, racial homogeneity, racial segregation in the city and metropolitan area, poverty population, and home ownership. Because our model suggests that provisions for direct democracy will influence government responsiveness to the average tax payer, we construct three variables that are interactions of initiative, referendum and recall with per capita personal income. Variables City financial and population data were drawn from published and on-line reports provided by the Bureau of the Census. These measures include city population, the proportion of the population that is non-Hispanic white, the proportion living in owneroccupied housing, and per capita personal income. Dissimilarity indices1 that measures of black white racial segregation were calculated from census tract data made available by the Lewis Mumford Center. 1. The following formula was used to generate segregation scores. 14 Data regarding the form of government and measures for direct democracy are taken from surveys conducted by the International City Manager Association (ICMA) in 1981, 1986, 1991, 1996 and 2001. The average response rate for the ICMA surveys was almost 80 percent, but some data for cities in the panel were missing in some years. Missing observations were filled in by relying on the general assumption that city constitutional-level institutions are not readily changed. If reported rules from the periods before and after the missing observation were identical, we coded the same form for the missing period. This assumes that cities did not adopt a constitutional rule, repeal it, then readopt it between the observations. This assumption may introduce some measurement error, but there is no reason to believe the error is systematic. As a result, it should not introduce bias. Results The pooled time series models of own-source, per capita revenue and fee dependence were estimated using ordinary least squares (OLS) with panel corrected standard errors (PCSE) (Beck and Katz, 1996). The data is transformed to produce serially independent errors and the Prais-Winsten transformation is employed (Gujarati, 1995). The OLS parameter estimates resulting from the estimation with PCSE are consistent, and the estimation process deals with panel-level heteroscedasticity and contemporaneous spatial autocorrelation (Achen 2000). In general, as Tables 1 and 2 demonstrate, our findings strongly suggest that institutional differences among cities lead to different fiscal choices. Perhaps most 15 importantly, these findings validate Masers’s (1998) contention that provisions for direct democracy serve different contractual functions. Specifically, cities with recall provisions which safeguards against defection problems (ie. Leviathan government) imposes lesser revenue burdens on their citizens and rely more on fees and charges instead or taxes. Table 1 estimates per capita municipal own source revenues. Provisions for initiative and referenda increase revenues but recall significantly reduces own-source revenues. Recall provisions reduced revenue by $508 per capita. Recall also has a significant and positive interactive effect with per-capita personal income. City revenue has a significant positive relationship with income, but where cities have a recall provision, this relationship is even stronger. Most of other variables in the model affect revenues as anticipated. Although the percent white increased revenues, council manager government, owner occupancy, and racial inequality in the metro area each reduce pre capita own-source revenue burdens as predicted. On the other hand, poverty and racial segregation in the city lead to higher own source revenues. (Table 1 about here.) The results shown in Table 2 demonstrate that cities with initiative or recall provisions are more likely to rely more heavily on the more efficient revenue sources of fees and charges than are cities without these constitutional measures, consistent with our expectations. Cities with initiative powers gain about 6 percent more of their own-source revenues from fees than other cities, while cities with recall provisions gather about 11 percent more. Referendum provisions and council manager government do not exhibit 16 statistically significant effects. The interaction of per capita income and the recall provision is again significant. Where cities charters include the recall, higher income leads to less reliance on fees. Black-white segregation in the city reduced reliance on fees and charges, while poverty rates and owner occupancy increased fee reliance. (Table 2 about here.) Discussion Over the past decade, a growing body of theoretical and empirical work has enhanced our understanding of the importance of institutions as nested systems. Our findings, although preliminary, suggest that the idea of nested institutions which establish contractual relations can enrich our understanding of cities’ policy choices. Perhaps most importantly, these findings validate Maser’s (1998) contention that provisions for direct democracy serve different contractual functions by demonstrating that city constitutionallevel rules that address stability, division and defection problems lead to different fiscal outcomes. The findings substantiate some of the nuances of rules’ effects in addressing problems of uncertainty and in creating incentives for opportunistic behavior. Constitutional level rules such as council-manager government or recall constrain political incentives that encourage opportunistic behavior and higher revenue levels. Other constitutional level rules, intended to make government more responsive to voter preferences, increase rather than curb revenues. These findings suggests that viewing cities as simply reformed or unreformed results in a substantial loss of information, which 17 leads us from the neatness of classification to the messiness of individual rules and their possibly interdependent effects. By reducing uncertainty, constitutional-level rules have been looked to as a means of decreasing uncertainty in order to restrain the growth of Leviathan. Our findings, however, suggest that, while the presence of rules exogenous to annual fiscal choices appear to affect Leviathan, they do not automatically contain it. A better understanding of the effects of different rules in shaping incentives under different conditions may make it possible to reconcile the median voter and Leviathan models of public finance. These initial analyses suggest that there is merit in further developing and testing a theory of nested institutions, but the model remains incomplete. Cities’ fiscal choices are conditioned not only by their own constitutional level rules but also by the powers and constraints imposed on them by their states. The nested institutions of cities are implanted within the nested institutions of their states. Most states authorize cities’ allowable sources of tax revenues and establish preferences for local policies (such as tax , borrowing or spending levels). By considering both the levels of government as well as levels of rules our future work will address how local institutional choices establish the way in which local policies will be made, the constituencies that will be served and the way in which state level preferences are implemented. 18 References Achen, Chris. 2000. “Why Lagged Dependent Variables Suppress the Effects of Other Explanatory Variables,” Paper presented at the APSA Political Methodology Annual Meeting, San Diego CA. Banfield, Edward and James Q. Wilson. 1963. City Politics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Beck, Nathaniel, and Jonathan Katz. 1996. “Nuisance vs. Substance: Specifying and Estimating Time-Series-Cross-Section Models.” Political Analysis 6: 1–34. Brennan, Geoffrey and Buchanan, James. 1985. The Reason of Rules. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Brennan, Geoffrey and Buchanan, James. 1980. The Power to Tax. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Chicoine, D.L. N. Walzer and S.C. Deller. 1989. “Representative Vs. Direct Democracy and Government Spending in a Median Voter Model.” Public Finance/Finances Publique. 44:2. 225-236. Coleman, Jules L. Douglas D. Heckathorn, and Steven M Maser. 1989. "A Bargaining Theory Approach to Default Provisions and Disclosure Rules in Contract Law." . The Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy, Vol. 12, #3, pp. 639-709, (Summer) 1989. Cronin, Thomas E.. 1989. Direct Democracy: The Politics of Initiative, Referendum, and Recall. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press. Dixit, Avinash K. 1996. The Making of Economic Policy. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. Feiock, Richard C. and James Clingermayer. 1992. "Development Policy Choice: Four Explanations for Economic Development Policies." American Review of Public Administration. 22: 49-65. Fischel, William A. 2000. "Municipal Corporations, Homeowners, and the Benefit View of the Property Tax." Paper prepared for the conference on Property Taxation and Local Government Finance sponsored by the Lincoln Institute for Land Policy, Paradise Valley, Arizona, January 16-18 2000. 19 Frant, Howard. 1996. “High-Powered and Low-Powered Incentives in the Public Sector.” Journal of Public Administration and Theory. 6: 365-381. Gerber, Elisabeth. 1996. “Legislative Response to the Threat of Popular Initiatives.” American Journal of Political Science. 40:99-128. Gujarati, Damodar N. 1995. Basic Econometrics. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill. Hamilton, Bruce. 1975. “Zoning and Property Taxation in a System of Local Governments.” Urban Studies 12: 205-211. Hansen, Susan. 1983. The Politics of Taxation. New York: Praeger. Heckathorn, Douglas D. and Steven M. Maser. 1987. “Bargaining and Constitutional Contracts.” American Journal of Political Science. 31: 142-168. Krane, Dale, Platon N. Rigos and Melvin B. Hill. 2001. Home Rule in America. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press. Lee, Eugene C.. 1981. “The American Experience, 1778-1978” in Austin Ranney, ed. The Referendum Device. Washington D.C.: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research. Lineberry, Robert L., and Edward Fowler. 1967. “Reformism and Public Policies in American Cities,” American Political Science Review 61: 701-16. MacManus, Susan A. 1978. Revenue Patterns in U.S. Cities and Suburbs: A Comparative Analysis. New York and London: Praeger Publishers. Maser, Steven. 1998. “Constitutions as Relational Contracts: Explaining Procedural Safeguards in Municipal Charters,” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 8: 527-564. Maser, Steven. M. 1985. “Demographic Factors Affecting Constitutional Decisions: The Case of Municipal Charters,” Public Choice 47: 121-62. Matsusaka, John. 1995. “Fiscal Effects of the Voter Initative:Evidence from the Last 30 Years.” Journal of Political Economy. 103:587-623. Matsusaka, John. 1992. "Economics of Direct Legislation." Quarterly Journal of Economics. 107: 541-571. McGuire, Therese J. 1999. “Proposition 13 and Its Offspring: For Good or Evil? National Tax Journal. 52: 129-138. 20 Miller, Gary. 2000. “Above Politics: Credible Commitment and Efficiency in the Design of Public Agencies,” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 10: 289-327. Miller, Gary 1985. “Progressive Reform and Induced Institutional Preferences,” Public Choice 47: 163-81. Morgan David R. and John Pelesserro. 1980. “Urban Policy: Does Structure Matter?” American Political Science Review 74: 999-1005. Milgrom, Paul and John Roberts. 1992. Economics of Organization and Management. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. Musgrave, Richard A. and Musgrave, Peggy B. 1976. Public Finance in Theory and Practice. 2nd edition. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company. Myerson, Roger B. 1995. Analysis of Democratic Institutions: Structure, Conduct and Performance. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 9: 77-89. Oates, Wallace E. 1985. “Searching for Leviathan: An Empirical Study” The American Economic Review. 75: 748-757. Ostrom, Elinor, et al. 1994. Rules, Games and Common Pool Resources. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Ostrom, Elinor. 1990. Governing the Commons. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Ostrom, Vincent; Tiebout, Charles M. and Warren, Robert. 1961. “The Organization of Government in Metropolitan Areas: A Theoretical Inquiry.” American Political Science Review. 55 831-842. Riker, William. 1982. Liberalism Against Populism. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman. Shapiro, Perry and Jon Sonstelie. 1982. “Did Proposition 13 Slay Leviathan?” The American Economic Review. 72: 2 184-190. Tiebout, Charles M. 1956. "A Pure Theory of Local Expenditures." Journal of Political Economy. 64. 416-424. Williamson, Oliver. 1981. “The Economic of Organization: A Transaction Cost Approach,” American Journal of Sociology 87: 549-77. 21 Williamson, Oliver. 1999. “Public and Private Bureaucracies: A Transaction Cost Economics Perspective,” Journal of Economics and Organizations15: 306-347. 22 Table 1 Own Source Revenues Per Capita Variable Coefficient Standard Error Constant 202.96 208.65 .97 Initiative 298.39** 125.64 2.38 Referendum 241.86* 136.35 1.77 Recall -507.36*** 117.82 -4.31 Mayor-Council Government -121.57*** 14.51 -8.54 Population -.00006 .00004 -1.52 Per Capita Personal Income .0503*** .0095 5.32 Income * Initiative -.0157 .0098 -1.59 Income * Referendum -.012 .008 -.1.56 Income * Recall .031*** .0078 3.95 White Population 1.477*** .478 3.09 Poverty Population 671.32*** 209.9 3.20 Homeowners -1058.56*** 90.88 -11.75 City Black/White Dissimilarity 8.582*** 1.038 8.27 Metro Black/White Dissimilarity -3.579*** .737 -4.86 N of cities 165 Observations 1465 Wald Chi2 7966.43 Prob > Chi2 .00 * ** *** significant at 90% confidence level significant at 95% confidence level significant at 99% confidence level 23 z-score Table 2 Reliance on Fees and Charges Variable Coefficient Standard Error z-score Constant -.026 .079 -.33 Initiative .60** .25 2.38 Referendum .019 .065 .30 Recall .115*** .036 3.23 Mayor-Council Government .004 .007 .60 Population -.4.48e-09 3.90e-09 -1.15 Per Capita Personal Income 7.82e-06*** 3.03e-06 2.58 Income * Initiative -1.36e-06 2.61e-06 -.52 Income * Referendum -1.85e-06 3.92e-06 -.47 Income * Recall -3.63e-06* 2.23e-06 -1.67 White Population -.0003 .0002 -1.23 Poverty Population .102*** .037 2.78 Homeowners .187*** .054 3.49 City Black/White Dissimilarity -.0008*** .0003 -2.94 Metro Black/White Dissimilarity .00009 .0003 .28 N of cities 165 Observations 1465 Wald Chi2 864.95 Prob > Chi2 .00 * ** *** significant at 90% confidence level significant at 95% confidence level significant at 99% confidence level 24