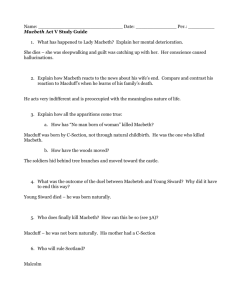

Title: Macbeth: What Does the Tyrant

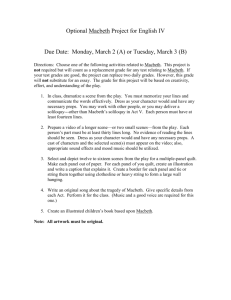

advertisement