embarkation fundamentals

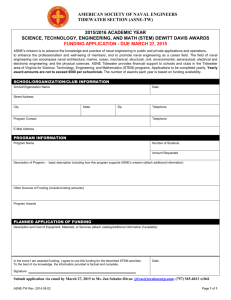

advertisement