Beowulf - essay 1.doc - WorldEnglishLiterature

advertisement

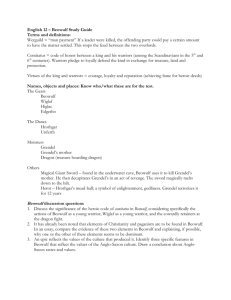

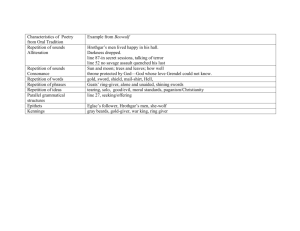

Rabb Andrews 1 Tamatha Anne Rabb Andrews (A87807) SP-7711 Lectura Dirigida I (British Literature) Prof. Alvaro Salas Ch. September 10, 2009 Beowulf: The Delusion of Evil in a Patriarchal Society “And the Lord said unto him, Therefore whosoever slayeth Cain, vengeance shall be taken on him sevenfold. And the Lord set a mark upon Cain, lest any finding him should kill him” — Genesis 4:15. According to the Old Testament, Cain, a tiller of the land, was the brother of Abel, a shepherd to his sheep, who in the heat of jealousy slew his own brother after God favored Abel’s sacrificial lamb over Cain’s crops. With this one act, the first murder had transpired on the face of Mother Earth itself —the mother to us all. The conflict between these two brothers reflects the ancient tensions between those who believe in the Triad of Divinity in a matriarchal society based on the Triple Goddess —“the Goddess in Her phases of Maiden, Mother, and Crone” (Morrison 4)— as opposed to the threefoldness of the patriarchal one God. As such, feminist mythic critics deal with what drives the social system of a culture and the underlying “norms and patterns” (Meyers 20) by analyzing a literary work through close analysis of its archetypal symbols and motifs. Such cultural symbols are manifested throughout an old Scandinavian story — Beowulf— which addresses the universally perceived issue of evil (Cain) in a patriarchal muted society. This epic poem was used as a tool by the English Christian monks who wished to convert the “pagans” —which simply means people who live in the country based on its Latin root word Pagani— to Christianity and a patriarchal order. A smear campaign thus commenced against non-Christians. As a means to extend the growth of the Church, monks put pen to paper and transcribed oral poems of old which were then grafted with Christian elements. These elements in Beowulf took the form of portraying the matriarchal Triple Goddesses as monsters —the Maiden as Grendel, the Mother as Grendel’s mother, and the Crone as the dragon— in order for the common people to forsake the Old Religion. The first of these “monsters” depicted in the poem takes the form of a “fiend from hell” (97)1 called Grendel by Hrothgar and his thanes. The characterization and imagery exploited by the author illustrates his desire to associate Grendel with evil. The foremost delineation of this character comes in the form of juxtaposing the creature with Cain: “He bore the curse of the seed of Cain/ Whereby God punished the grievous guilt/ Of Abel’s murder” (103-105). The description continues in noting that Grendel is a decedent of Cain whose ancestors have been defeated time and time again by the Lord Almighty: Of his blood was begotten an evil brood, Marauding monsters and menacing trolls, Goblins and giants who battled with God A long time. Grimly He gave them reward! (108-111) The patriarchal depiction of Grendel expands further with the use of a variety of kennings to portray this personage as evil to the very core of its being: “shepherd of sins” (708), “foe of God” (746), and “hell-thane” (748) as it was the wish of the Church to deface the matriarchal deities in order to eliminate a rival religion. The author’s employment of other descriptive words 1 All quotations in this paper, unless otherwise cited, are from the epic poem Beowulf. Rabb Andrews 2 furthers this smear campaign at a word choice level such as the use of “demon” (99, 158, 670, and 699), “hell-thane” (748), and “fiend from hell” (97). The pattern of depicting Grendel as evil goes one step further by consistently associating “the savage monster” (692) with death, destruction, and darkness as the author describes the following scene: Not longer was it than one night later The fiend returning renewed attack With heart firm-fixed in the hateful war, Feeling no rue for the grievous wrong. (133-136) “The fiend” (667) who haunts “the hall in the hateful dark” (166) is portrayed as having no remorse, whatsoever, for the slaying of thirty men the night before which was motivated by a lust for evil, according to the patriarchal telling of this tale, and Grendel’s inability to endure the song of the bard singing about the story of Creation in lines 85-95. The contents of the scop’s song of God’s creation of the world contrasts with Grendel and his world which can be associated with destruction through the lens of “the One.” Grendel’s lair may also be associated with death, darkness, and destruction as images of the “fiend from hell[’s]” (97) mere is juxtaposed with the image of hell: The antlered hart hard driven by hounds, Invading that forest in flight from afar Will turn at bay and die on the brink Ere ever he’ll plunge in that haunted pool. (1254-1257) At a misogynic, archetypal level, Grendel’s characterized evil would place the Maiden into the category of the femme fatale as this “monster” (720) is constantly being linked with “fear, danger, darkness, emasculation [up until he met Beowulf in battle illustrated in line 766 to line 768], and death” (Guerin 187). But by shifting the “lens” to view Grendel —the giant— in a matriarchal representation through the use of symbology, one may be awakened to the muted truth so long buried by Christianity. According to Cirlot, the giant is characterized as a guardian in folklore and “defender of the common people against the overlord [who uphold the individual’s as well as the tribe’s] liberties and rights” (Cirlot 118). As such, the Maiden is portrayed using the “the positive aspects of the Earth Mother” (Guerin 187) as she watches over the fertility of crops as well as the tribe, but Christian tradition muted the Old Religion’s characterization of the giant by associating this being with night, subterranean life, and Satan, according to Tresidder. The second “monster” portrayed as evil in the Scandinavian story of Beowulf concerns Grendel’s mother. The author again associates this “monster” (1161) with the Old Testament curse of Cain: From ancient ages when Cain had killed His only brother, his father’s son. Banished and branded with marks of murder Cain fled far from the joys of men, Haunting the barrens, begetting a brood Of grisly monsters; and Grendel was one, (1153-1158) By relating this personage with the first murder, the Christian clergy were able to guarantee an aversion to the Triple Goddess as it was deemed a heinous act among Anglo-Saxon noblemen to kill one’s kindred as Wergild, man-payment, was not a satisfactory recompense to the relatives of a slain kinsman. Death by kindred by kindred, then, could not be appeased. Word choice and several kennings were also used to portray Grendel’s mother as an evildoer in a Rabb Andrews 3 patriarchal society: “hag” (1150, 1183, 1384, 1426), “demon” (1219), “fiend” (1504), “sea-troll” (1386, 1403), “she-wolf” (1392), and “sea-wolf” (1484). By gazing at this epic poem through a clear “lens” one may observe over the course of history that the “gods of an old religion become the devils of a new” (Buckland 4). This poem represents the struggle which began with the birth of the man-made Christian religion which continuously debased itself with the use of a campaign slander in order to obtain followers. “Missionaries were particularly prone to label all primitive tribes upon whom they stumbled as devil-worshipers, just because the tribe worshiped a god or gods other than the Christian one” (Buckland 4). The depiction of Grendel’s mother as having the same diabolic aspects as her son in the case of the poet’s images of death, destruction, and darkness further debases the Old Religion while supporting the new patriarchal order. The reader first becomes aware of her dark, fatal nature when analyzing the following lines from the poem: “She stole to the hall where the Danes were sleeping, / And horror fell on the host of earls/ When the dam of Grendel burst in the door” (1171-1173). “The hag” (1183) at this point has been provoked by the demise of her son through the agency of Beowulf. As such, her attack on Heorot holds a twofold purpose: on the one hand, to obtain revenge for the life of Grendel and on the other, to reclaim “the blood-stained claw” (1194) of her son. With the act of seizing and beheading Hrothgar’s “closest of counsellors” (1213), she achieves her first aim, and the taking of the battle-“token” (787) from “the gabled hall” (789) the second. Grendel’s and his mother’s lair are again associated with death, darkness, and destruction as illustrated through the poetic imagery: “Sudden they came on a dismal covert/ Of trees that hung over hoary stone, / Over churning water and blood-stained wave” (1300-1302) which once more contrasts with the image of Creation sung by the bard toward the beginning of this tale: A skillful bard sang the ancient story Of man’s creation; how the Maker wrought The shining earth with its circling waters; In splendor established the sun and moon As lights to illumine the land of men; Fairly adorning the fields of earth (88-93). Then at a patriarchal, archetypal level, “the mother of Grendel, a monstrous hag” (1150) can be placed in the category of the terrible Mother as she is consistently being depicted as a hag or witch not to mention being characterized as a lamia and a dealer of death. Once again by shifting the “lens” to a matriarchal perspective of the Mother’s personage of the goddess, one may unearth her true self as the embodiment of fertility. As such, women are the bearers and nursers of the young since time began. “The Goddess was her representative as the Great Provider and Comforter; Mother Nature or Mother Earth” (Buckland 2). The third and final “monster” used to attenuate the Triad Goddess as an evil being in a Christian patriarchal society is namely the symbolic dragon or “worm” (2153). This creature was not directly tied to the sins of Cain but to a much older sin in the Garden of Eden, “who persuaded Eve to eat of the tree of knowledge of good and evil and thus brought about the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the garden and the advent of death” (Ferrer 186). Through this perspective, the dragon is perceived as the personage that foreshadowed the arrival of evil and more specifically death itself on earth. “In the Christian scheme the serpent of Eden became ‘the great dragon’” (Ferber 186) which was later directly attached to the devil in the New Testament. “Christianity was the primary influence behind the evolution of the dragon into a generalized symbol of adversarial evil” (Tresidder 157). The poet took this to heart with his Rabb Andrews 4 uncanny ability in word play in portraying an evil, dark, destructive antagonist in the world of men as seen in the following kennings and descriptive phrases: “fire-drake” (2082, 2160), “waster of peoples” (2144), “hoard-warden” (2168, 2411), “hostile flier” (2180), “deadly worm” (2265), “monstrous warden” (2277), “dire destroyer” (2372), “flying serpent” (2386), “monstrous dragon” (2392, 2542), “great worm” (2423), “flame-breathing dragon” (2425), “hideous foe” (2524), and “evil beast” (2553). Once more, a pattern was used to characterize the “monster” (2154) as a representation of death and destruction with an evil intent on the world of man: Then the baleful stranger belched fire and flame, Burned the bright dwellings— the glow of the blaze Filled hearts with horror. The hostile flier Was minded to leave there nothing alive. (2178-2181) The evilness of “The guard of the mound[’s]” (2169) action was roused after a thief plunders a jeweled cup from among the treasures he was sleeping upon for hundredths of years. Again, the poet depicts the “monster” as having no remorse for the fiery hells it rained upon the world of man. As with the tale of Grendel and his mother, creation is once more contrasted with the destructive actions of a monster. Whereas at the beginning of Beowulf when the scope sang of God’s creation of the world, the poet now sings of the screams and shrieks of pain due to the battle for the survival of Creation which has been repeated for the third time in this poem, but under the “lens” of a patriarchal Christian order, God will rein in the end as seen in line 111. Finally, at an archetypal viewpoint, the dragon, or Crone under the Triple Goddess, is seen as the symbolic serpent which encompasses “evil,” “corruption,” and “destruction” according to Guerin. Then again, as always, one should awaken when analyzing a work of literature to see an inverse characteristic being depicted. Thus, according to Cirlot, women were equated with dragons symbolically as a “mother-image” (Cirlot 88). These beings were also “turned into an allegory of prophesy and wisdom” (Cirlot 87). Through this matriarchal perspective, the Crone or dragon may be seen in its positive aspects of “energy,” “pure force,” and “wisdom” ---above all--- by Guerin. As seen with each of the “monsters” recounted in this tale, Christianity had inverted the tales of old to bring about the new religion based on a patriarchal society. That being said, one may take a different interpretation of the serpent in the Garden of Eden as having the creature “trying to bring true wisdom and divinity to Adam and Eve, who were trapped in the fallen world by a wicked creator god” (Ferber 186). Beowulf reveals the hypocrisy of Christianity, and the lengths it took to convert the “pagans” of old to a new system of beliefs by creating images of evil overlaid on the once beloved goddesses of the Old Religion. The poem unveils an age when the stories of the Original Sin and the curse of Cain shaped the belief system we have today. Since the dawn of putting tales to paper, the hegemonic group dominated the will of society. With its use of smear campaigns over the centuries against any religion that did not belief in the three-folded God, we are now in an age of evil that enfolds and encroaches upon us daily. How heavyhearted to know that once upon a time there was a peaceful religion where “people were good, happy, often morally and ethically” better off “than the vast majority of Christians” (Buckland 4) . . . but we just had to be converted. Rabb Andrews 5 Works Cited Buckland, Raymond. Buckland’s Complete Book of Witchcraft. Minnesota: Llewellyn Publications, 1996. Cirlot, J.E. A Dictionary of Symbols 2nd Edition. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1971. Ferber, Michael. A Dictionary of Literary Symbols 2nd Edition. UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007. Guerin, Wilfred. A Handbook of Critical Approaches to Literature 5th Edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. Morrison, Dorothy. The Craft 5th Edition. Minnesota: Llewellyn Publications, 2003. Pacheco, Kari. The Perceptive Process: An Introductory Guide to Literary Criticism. Costa Rica: Editorial Universidad de Costa Rica, 2003. Tresidder, Jack. The Complete Dictionary of Symbols. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2004.