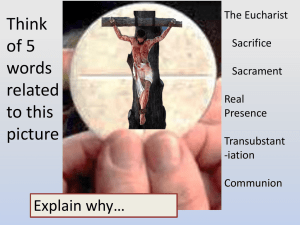

Sacrifice of the Mass: Do Catholics Re-crucify Christ

advertisement