Chapter I: The Sociological Imagination

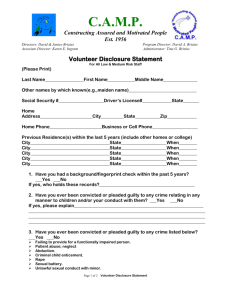

advertisement

Malón, Chapter 1, page 14 Chapter I: The Sociological Imagination Abuse Research In my first readings regarding the phenomenon of child sexual abuse, I encountered a phrase from one of the most recognized researchers into the matter, David Finkelhor, to which I shall make frequent reference throughout this book. The aforementioned author, participating in a congress on child maltreatment, stated that "research into sexual abuse is still in its infancy" (Finkelhor, 1993, p. 215). That phrase, in its simplicity, immediately peaked my interest, perhaps because it would acknowledge the possibility of bringing new understandings into the area which I was establishing for myself as an object of study. I would continue with my investigation, driven in part by the idea that we still have a great deal to learn about the sexual abuse of minors; but curiously, what had originally been the spur to my investigative efforts would end up transforming itself into a question central to my work, which would have to be at least partially addressed in order to proceed: What is there really left for us to learn about child sexual abuse? No matter how much one might read, the repeated impression one gets is that we already know everything, that the conclusions have been there, systematic and irrefutable. The contributions of ever more abundant researchers and professionals who have been rushing out to write about the matter would seem to be more in the nature of immutable truths than theoretical inquiries. In fact, doubts have been conspicuous by their absence, and if any should arise from time to time, they would be dealt with more as secondary aspects of the phenomenon than its central ones. The reality of sexual abuse has, therefore, showing itself to be clear and transparent; a simple one, both hard and terrible but always evident, well-known. The steps were elemental; the line of work, concrete. I was not encountering any doubts, and I was asking myself what I would be able to contribute to its study if there wasn't anything left to discuss, if there weren't any remaining Malón, Chapter 1, page 15 dilemmas to rethink or gaps to be filled in. We already know what abuse is and how to act when faced with it; we also more or less know why it occurs and what consequences it has; we know its extent and its statistical description down to the smallest detail. In that case, what's left for me? I was not be able to avoid the impression, perhaps erroneous, that there wasn't much left to establish; only to continue on this same course and, at most, summarize how to go about it. If, as Durkheim would say, "It is science, not religion, that has taught men that things are complex and difficult to understand" (1992, p. 25), my sense would be that what we have before us are priests, not scientists. And, continuing with Durkheim, this would coincide with his notion that: As far as social facts are concerned, we still have the modality of primitives. And nevertheless, if, in matters of sociology, so many present-day persons are still stuck in this feeble way of thinking, it is not because the life of societies seems obscure and mysterious to them; on the contrary, if they are so easily satisfied with these explanations, if they persist in these illusions which experience is incessantly contradicting, it is because social facts seem, to them, to be the clearest thing in the world; it is because they do not perceive their actual obscurity. (ibid, p. 25) There would then arise, in repeated form, the complex relationship between the scientific and the social, between research and professional practice. Raymon Aron, in his prologue to Weber's (1997) book The Politician and the Scientist, develops an interesting analysis of this relationship in terms of the scientists and politicians involved, in the broadest sense of the word, warning of the risk that science takes in letting itself fall into the snares and interests of the state. To Aron, science has the intrinsic capacity to break with the social mythologies by going inside social objects and disentangling their inherent complexity; just as Durkheim had asserted. Malón, Chapter 1, page 16 If we aren't careful Aron tells us in his prologue to Weber the concepts of science will be converted into characters from mythology, confounding our schemes of reality, neglecting the multiple meanings of complex phenomena that are designed terms like capitalism and socialism, and quickly substituting one for another. We are not, then, presently confronted with men and institutions, or with the imminent significance of their conduct or the structure of those things, but with a mysterious force that has kept watch over the meaning we have ascribed to the world but which has lost contact with the facts. (Aron, in Weber, 1997, p. 32) In this sense, it is useful to divide the proposals that child sexual abuse researchers have made regarding their current work from those relating to future research. The same author with whom I initiated this section, David Finkelhor, devoted one of his most notable works on child sexual abuse to expounding on a proposal as to precisely how social science ought to approach this problem. In the preface to the book, entitled Child Sexual Abuse: New Theory and Research (1984), he explains how that work attended to theoretical requirements and research in this field. The fact was, according to him, that at the time this was written, there was a perceptible gap in these areas, with the lion's share of works focusing on other aspects, such as the treatment or experiences of the survivors. I believe that Finkelhor is correct. There is a plethora of abuse research into the problem of one's victimization and the other's pursuit and punishment. It is essentially cross-sectional forensically and therapeutically oriented research. It is possible that this is due to the fact that sexual abuse, as its very name would indicate, leads directly to a kind of harm which, as we shall see, is seen as inevitable. It is an evil associated with the sexual by definition, which could not have been so except in a culture like ours. It is an obvious fact: the problem of child sexual abuse has Malón, Chapter 1, page 17 emerged within modernity's uneasiness with astonishing contentiousness in the space of little more than two decades. Discourses relating to the phenomenon have multiplied, generally in an ongoing tone of denunciation and alarm. Moreover the social implications are of such gravity, that there are, I believe, few other times when such a concept of evil would have been used by social scientists to explain a phenomenon of such broad dimensions, perhaps with the exception of masturbation into the 18th and 19th centuries (Malón, 2001). In the face of this deficit of sociological insights, which evidently affects how child sexual abuse is viewed, and which also was denounced by Plummer (1981) in what he refers to as the proximate subject of pedophilia, Finkelhor offers us other approaches. His objective, he says, was to present and suggest answers to some new questions, such as the following: How is it possible that there could be so much abuse, given the intense social taboo regarding it? Why do these acts seem so horrendous to us? Why do some children suffer it, whereas others do not? These, Finkelhor tells us, would be applied within a theoretical framework which seeks to approach the problem more from a sociological point of view than the customary psychological one. Secondly, referring to the field of inquiry, he suggests, especially, the need to carry out studies of a sociological nature, focused on the gathering of data, systematic observation, and statistical analysis that answer questions such as: What are the short- and long-term consequences of abuse? Or, what groups of children are at greater risk? He proposed these last two questions as fundamental, and we would do well to ask ourselves: What are the premises and intentions that correspond to all of these questions, so prioritized? Finkelhor dedicated an entire chapter to reflecting upon abuse as a social problem. A chapter in which he presented questions which turned out to be of interest to me, such as why the surge in social uneasiness over abuse and the consequent increase in accusations might have Malón, Chapter 1, page 18 occurred, the question of whether we are dealing with a new problem or one that already existed but was not condemned, or how past cultural transformations in matters of sexuality might have influenced the genesis of the aforementioned phenomenon. Unfortunately, though he had already previously explained that this was going to be the general tone of the book, he did this in a very superficial way, and did not go into that which is of most interest to me. I am referring to the consideration of this same phenomenon, child sexual abuse, as an object of sociological reflection, in a way that will allow us to respond in greater depth to the questions that keep cropping up as we approach it: Why is the sexual abuse of minors now a social problem? How and from where has this occurred? Why in such a dramatic way, and why at this point in history? What type of social problem do we really have here? What values, anxieties, and beliefs are in play? How has this unfolded socially? Where has it ended up, and within what frameworks and in what way has this occurred? In the final analysis we must ask ourselves what is child sexual abuse? What are we talking about when we talk about abuse, and how do we talk about it? In this book, I want to present a proposal for an approach which favors a comprehensive, distinct, and fresh perspective on the phenomenon of child sexual abuse and the way in which it has been configured and dealt with by modern western societies. It is my intention to defend the need for a different sociological approach to this issue, going beyond the vast majority of explanations provided and studies done up to this point, which give the impression of responding more to political and professional exigencies all of them very respectable and perhaps necessary than to theoretical questions of a different order. No matter how much they rely on large statistical studies and make reference to supposed social elements of the problem, I believe that in their approaches researchers have confined themselves by those very same things, for reasons which we Malón, Chapter 1, page 19 will discuss. Therefore, it is no wonder that one observes a monotonous repetition of ideas and discourses in research, articles, and books about the matter. To think that the only truly interesting social problem boils down to an adult who abuses a girl or a boy, and that our most pressing preoccupation as researchers has to be repudiating and abolishing these acts, means making the exigencies of the politician one's own, adopting his same pragmatic priorities and neglecting the real work of the theoretician. I believe, then, that it is possible to argue that, in research, with few exceptions, priority has been given to understanding child sexual abuse as an individual problem that needs to be investigated in order to be combated, on the basis of certain questionable and insufficiently grounded premises. I, for my part, shall propose the necessity of seeing them as a new social reality that we would do well to become acquainted with, precisely in order to understand our own society. The point of departure of the present work will be to defend the idea that truly understanding the problem of child sexual abuse as a social issue requires going beyond abuse as aggression, crime, or deviance in order to approach the study of everything that surrounds the phenomenon, before and after it, including of course scientific knowledge generated with respect to it. As Plummer (1981) noted, it is necessary for scientists to dispassionately dedicate themselves to listening to the discourses, to the stories of children, adults, and groups, and to coherently place those accounts into the broadest context of history and social structure. Saving victims and condemning aggressors may be very urgent to some, but I ask whether that is the sole purpose that should guide our research efforts. For my part I shall not proceed on this basis, no matter how much that may leave me open to criticism. I want to stress that it is not my intention to reject any type of research or perspective, because I firmly believe that all of them have something to contribute though I also believe that, Malón, Chapter 1, page 20 as of this point at least, some have more than others. But it is, in fact, my intention to work towards a course which seeks to comprehend "child sexual abuse" as a cultural reality to be understood, and not as a social problem to be solved, so that we can begin to sketch out the contours of this subject just as we perceive them in our investigation. By way of negation, in this study child sexual abuse is not simply as I have already suggested an experience, a crime, a problem, or an aggression; it may be some or all of these and much more. That complex phenomenon, which we have provisionally come to call "child sexual abuse," will be understood as a constellation of discourses, beliefs, and actions which form an active part of the social mechanisms established to regulate society and hence its individuals. In fact, I am going to suggest that it might be more useful for us to see it as a danger that may need to be prevented. Or better yet, as a new moral code from which to fashion both of these things. Sexual Abuse as Social Discourse Every culture has its own risks and problems. ... In order to understand bodily defilement, we should compare society's unrecognized dangers with known corporeal themes, in order to try to discover what form they take (Douglas, 1991. p. 141). A mother, facing the klieg lights of a string of Mexican television cameras, recommends to all mothers that they remain on the alert and protect their daughters from possible "sexual" approaches by their fathers, stepfathers, or other male family members; it may seem unbelievable, she says, but it happened to her and it is necessary to avoid it; for it is only through attentiveness and a perceptive eye that prevention is possible. Educational and protection authorities, through trained professionals and investigators, establish educational programs for boys and girls in order to teach them to protect themselves from sexual abuse that might well be committed by strangers, or, more typically, by those nearer to them. A prosecutor of crimes against minors from a large Malón, Chapter 1, page 21 Spanish city orders the seizure of suspect photos of a minor female from the show window of a photography store and instructs her parents, who had commissioned said photos and allowed them to be displayed in the establishment, perhaps without meaning to do anything wrong, about the risks to the minor that these types of activities entail; their daughter's body is sacred, and they have to protect it. A social worker, attached to the juvenile court of a city in Central America, advises a grandmother who is looking after her granddaughter the girl's mother is a prostitute and was not allowed to keep her that the girl not be seen in suggestive clothing and that there is a risk that her step-grandfather, suspected of having committed abuse in the past, intends to sexually abuse her; the girl is six years old. Following the allegation of a lewd act having been committed by one minor upon another at a youth center, that same Court becomes uneasy and questions those responsible for the center about the programs and mechanisms that that institution has put in place to prevent this sort of aggression; a court psychologist is quickly dispatched to give a talk to the center's staff about how to comport themselves in front of the children and youth in order to prevent any possible abuse. That same psychologist explains, during an appointment with a grandmother worried about her granddaughter, the dangers that lurk behind the suspicious figure of a stepfather. Explaining the existence of these activities as reflecting the logical responses of society and its institutions to the problem of child sexual abuse, with the basic and laudable objective of protecting actual or potential victims of these acts might appear reasonable; nevertheless in my opinion everything is not as reasonable as it would seem, nor does it presuppose a minimally valid explanation of the phenomenon. It is possible that on the level of public discourse or individual rationalizations this would be the reason put forth; as Douglas says, "The attribution of danger is a way of placing a subject beyond all discussion" (1991, p. 40). Nevertheless the sociological Malón, Chapter 1, page 22 imagination (Wright Mills, 1993) requires us to go further, in order to try to bring about a better understanding of that aim. What the five examples given here all of them real have in common is that they are a question of actions oriented towards the establishment and prevention of a certain risk and danger. They would be something in the nature of alarm calls, at the same time including practical instructions or "avoidances" to use the Freudian term (Freud, 1912/1962) employed to conjure up such dangers. But these actions go further than that claim, containing within them much more important meanings, since in a way they are but actions employed in order to create and re-create a social world through the emphasis of certain risks and the implementing of certain practices but not others employed in order to prevent them. Even more than it is a problem, "child sexual abuse" is a discourse, or part of a new universalized discourse, of "abuse." A modern social discourse, and therefore a moral one, which is emerging and implanting itself into all of society, into its institutions and individuals, relying moreover on a language of its own, on legal codes, a structure, an internal logic and in short on an all-encompassing perception which acts as a mental regime within which to interpret reality. The world, or a significant portion of it that of relations between the sexes is interpreted in terms of abuse. It is claimed that we do not have any other terms at our disposal, any other alternative. The new moral language of "abuse" has come to replace old terms like sin or honor. Before, we told ourselves, everything was sin; today everything is abuse. Moreover it is, as we shall see, a broad discourse, elastic, within which there can be room for diverse realities, desires, experiences, and objectives. Some adapt better; for others, which will have to be conveniently concealed, it is more difficult. And it is a question, ultimately, of a discourse of danger, a language in which danger, latent and dispersed throughout all parties, is employed anew as a system of social control, regulation, and power. This is precisely, I believe, the perspective which best enables us to Malón, Chapter 1, page 23 contribute to its study, and it is the analysis of social reality that will give us the framework within which to do it. I wish to approach and talk about child sexual abuse as a discourse characteristic of our society. And I wish to talk about it in terms of the images of moral contamination that it contains, focusing not only on its particular criminal implications, but also on its connection to our society's moral order. And I want to do it in this manner because I am reasonably well-acquainted with the hypothesis which says that the anxious way in which the phenomenon of the sexual dangers menacing childhood has been conceived loaded with intense emotions, dramatic dimensions, and disastrous personal and collective consequences corresponds more to ideological and moral controversies than to rational and reasonable practices. So-called child sexual abuse, referring to practically any "sexual" interaction involving a minor, especially when it is with an adult, is the central focus of disorder threatening the very foundations of our culture. Its discovery and the response which it has received would not appear to be comprehensible simply in terms of a proportional response to a crime. Its accentuation in recent decades should not be explained simply in terms of a rise in the social and professional awareness of a real problem, although some of this is necessary. What I seek is to justify the necessity and I hope the utility of approaching its study without even the slightest trace of surprise or astonishment at the phenomenon's magnitude and form. I will try to demonstrate the usefulness of analyzing the multi-faceted phenomenon of child sexual abuse as a socially-constructed object which forms a part of the whole social order, and at the same time constitutes it. For we are within a territory that may be delineated by the convergence of three concepts which the West has bound together tightly for many years now: childhood, sexuality, and danger. Malón, Chapter 1, page 24 It is my intention to better understand the position which all of that emerging discourse about the dangers associated with the union between sexuality and childhood occupies in our modern Western societies. In his book The Sociological Imagination, Wright Mills would say that "Social science deals with problems of biography, or history, and of their intersections within social structures...those three things biography, history, and society are the coordinate points of, the proper study of man" (Wright Mills, 1993, p. 157). I believe that that task is, in large part, yet to be done as far as the social problem of child sexual abuse is concerned. Reading Guide and Final Observations The remainder of this work is composed of four parts, well-differentiated into the same number of chapters, as well as a final epilogue. Taking selected readings as my point of departure, in Chapter II I undertake a detailed analysis of the social context in which the modern danger of sexual abuse arose in the United States of the 1970s and 1980s. In the aforementioned process, privileged positions were occupied by certain feminist discourses that proclaimed the notion of masculine desire as a source of danger, a right-wing moral politics imbued with fanatic and satanic tinges, backed by a broad social base in crisis due to recent transformations in areas like sexual morality, new political strategies in the area of the protection of minors and, finally, social panics which stirred up a general sense of horror and menace surrounding sexuality. In Chapter III, I analyze and question what, in my opinion, are the three traits characteristic of how this modern dread of the sexual abuse of minors is defined. These traits are its presentation as an indisputable truth whose questioning is supposedly anathema; the terrible and unprecedented extent to which the existence of the problem has been highlighted; and, finally, the traumatic gravity characterized as inevitably inherent in these experiences. Malón, Chapter 1, page 25 In Chapter IV, I critically review the increasingly combat oriented language that dominates the field. So-called zero tolerance for abuse appears to be a premise undiscussed by anyone but which, in my opinion, corresponds especially to ideological strategies whose negative consequences will not take long to make themselves evident. In this chapter I question the logic of this sweeping battle, some of its possible effects on professional practice, and the role granted to the justice system and penal codes in solving this problem. In a penultimate section I return to the origin of the work, expounding on my cultural interpretation of the way in which the subject of abused minors has become ever more present, thereby transforming itself into that generalized danger which is so well-suited to our epoch. I will try to look at how children's bodies and sexuality serve to articulate definite visions of society and its members, imposing social perspectives and sometimes producing uncontrollable consequences. Finally, in an epilogue, I present some fundamental questions regarding the effect that this entire discourse about sexual trauma and dangerousness could end up having on the configuration of sexuality in modernity and on our way of understanding and confronting the moral conflicts and dilemmas that we experience. One final consideration: It is possible that to some, it will appear that this book lacks the necessary sensitivity towards the suffering of victims, and even that this suffering is questioned, or at least relegated to secondary status. Certainly my criticism is oriented in good measure towards the excesses that have been able to bring about an exaggerated victimistic mindset that has been promoted in the area of the sexual abuse of minors. I therefore shall attempt to demonstrate that this is a product of the ideological and symbolic use that has been made of this issue and the dramatic vision of it which has been disseminated, without taking account of variations, or shades of gray. It is equally certain that the focus of my work is not sexual abuse as a problem that requires Malón, Chapter 1, page 26 denouncing and combating. We already have at our disposal an ample literature along these lines which has dedicated itself to that, and which in good measure is criticized in the present work. In fact, one of the consequences of my proposal is, I believe, to suggest that it would be interesting to investigate the topic via avenues other than the development of intervention programs and guidelines. Nevertheless and I shall not cease to feel obliged to explain myself, given the tone that the public debate on this matter has acquired all of this does not mean that as a researcher I am unmoved by the suffering that lay behind many of these experiences, which had already become apparent to me through the reading of books, in conversations with professionals, and in reviewing the documents that I prepared during the fieldwork undertaken for my doctoral thesis. Without forgetting or denying this suffering, what I am perhaps questioning here is in what form, through what strategies, and at the cost of which values, are we going to bring about the desired social transformation in order to avoid this pain. And for that matter, I am particularly interested in critiquing and questioning the way in which the sexual has been understood at the time that certain more serious experiences, as well as others which I dare say pose little risk of contradicting the principles of the modern abuse discourse, are interpreted. As a researcher I have acknowledged that my point of departure for this book was clear: to not automatically believe in the horror of abuse which is reflected in what has been said and written about it in specialized books, manuals given out, pamphlets, the media, novels, etc. Neither do I share the view that fear and over-dramatizing are useful either in transforming a society or in protecting its individuals, be they children or adults.