The Market Empire in the Age of Victoria

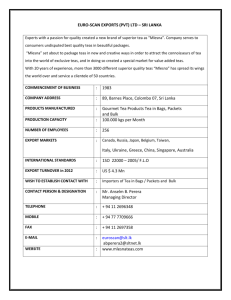

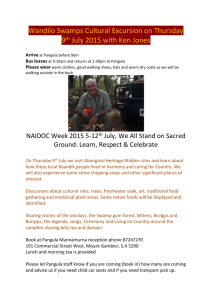

advertisement