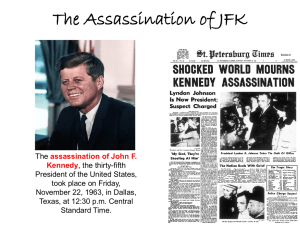

Warren Report: Table of Contents

advertisement