COSATU SUBMISSION ON THE WALMART/MASSMART MERGER

advertisement

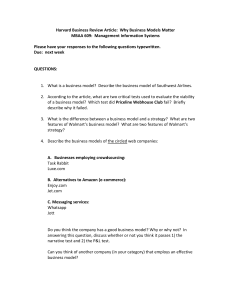

COSATU SUBMISSION ON THE WALMART/MASSMART MERGER PRESENTED TO THE PORTFOLIO COMMITTEE ON ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ON 20 JULY 2011 Contents 1 2 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 2 1.1 Our Approach to Consumer Prices and Further Regulation ................................................... 4 1.2 On Public Interest Generally ................................................................................................... 6 SPECIFIC COMMENTS ON THE TRIBUNAL’S ORDER ............................................................. 7 2.1 On the Relevant Market and the Impact on Competition ........................................................ 7 2.1.1 2.2 Public Interest Demands ....................................................................................................... 10 2.2.1 2.3 Vertical Integration .......................................................................................................... 8 On Retrenchments, Labour Matters and Collective Bargaining .................................... 10 On Procurement .................................................................................................................... 11 1 INTRODUCTION When the Competition Tribunal published its reasons for its approval of the merger of Walmart and Massmart it made the following (and now much publicised) statement: “Our job in merger control is not to make the world a better place, only to prevent it becoming worse as a result of a specific transaction”. In a country that is burdened with high rates of structural unemployment and poverty and which is now considered to be the most unequal in the world, the first part of that statement reflects a lack of sensitivity to the adverse consequences that inappropriate interpretation of competition laws may have for entrenching these patterns. We must disagree with this narrow interpretation of the Tribunal’s jurisdiction that this refers to. And we must disagree even more strenuously with its decision to approve the merger. Considering Walmart’s deplorable record globally on labour rights and repressive attitude to trade unionism, indiscriminate use of suppliers who violate environmental, health and safety standards, and general disregard for compliance with competition rules to the detriment of other industry players, jobs and livelihoods, we can only 2 argue that our corner of the world is in far worse a position as a consequence of the Tribunal’s decision. We remain convinced that Walmart’s takeover is not in the best interests of this country and will continue to oppose the deal. Under the Competition Act, the Competition Tribunal must consider the competition and public interest effects of a proposed merger, and not just the narrow interests of the firms who intend to merge. In its ruling on the Walmart/Massmart merger, we believe it ignored the wider interests of the workers in both Massmart and other retailers, South African manufacturers and the developmental interests of the country as a whole. Further we would argue that even if the decision were to be measured against addressing narrowly-defined competition-aligned objectives it would fall far short of meeting the standards in the Competition Act. Given Walmart’s size and notorious business practices around the world, the Tribunal should have weighed the supposed value of Walmart’s investment in South Africa against its foreseeable adverse impact on jobs and conditions, in both the retail sector and in manufacturing and other sectors that feed into the supply chain to Massmart such as agriculture, agro-processing, chemicals, clothing and textiles Accordingly COSATU welcomes the opportunity to participate in the public hearings on the implications of the Competition Tribunal’s decision. We commend the Portfolio Committee for providing the space for stakeholders in the public sphere to table their concerns on this issue. However, considering the complexity of competition law and its processes it is likely that broader civil society has yet to fully take stock of the associated adverse consequences. Accordingly we would call on the Committee to consider further processes that would enable broader and popular participation. It should be noted that SACCAWU has already filed a notice of its intention to appeal the Tribunal’s order to the Competition Appeal Court. In addition COSATU has filed a section 77 notice with NEDLAC (the National Economic Development and Labour Council) to embark on protest action, and hereby signal that we will strongly maintain 3 our resistance to the implementation of this merger decision for as long as it is necessary. At the outset we wish to state categorically we believe that the Tribunal erred in its decision, as we will expand in this submission. However, we will first comment on certain related substantive considerations that frame our approach as well as our expectations from this and future processes on competition law. This decision has highlighted the broader problem with our competition legal framework. 1.1 Our Approach to Consumer Prices and Further Regulation We have consistently raised our concerns about excessive consumer prices especially in relation to basic foods and services and the hardship it creates for the poor. We have also criticised collusive behaviour amongst corporates that engage in price fixing. One of the most notorious examples relates to the bread price-fixing scandal that led to Tiger Brands, Foodcorp and Sasko being respectively fined R98.8 million, R45 million and R195 million by the Competition Commission in. Tiger Brands again in 2008 “agreed” to pay a R53.5 million fine in response to charges for anti-competitive conduct in relation to its then health care subsidiary, Adcock Ingram Critical Care. In 2008 the Competition Commission completed an inquiry into banking charges and found them to be too high. All of these only begin to illustrate the magnitude and complexity of the challenges we face. Our opposition to the approval of the Walmart-Massmart Merger, which appears to be heavily premised on the issue of lower consumer prices, must not therefore be construed as indifference to the necessity to ensure fair, transparent and affordable consumer prices. However, the Walmart decision illustrates slavish faith in the flawed principle that we must be dependent on free market principles to deliver fair pricing without enquiring into the social costs and who must bear them. More generally we note that punitive actions taken by the Competition authorities as noted above, have not translated into broader general relief for consumers. More 4 recently investigations have come to be dependent on corporate leniency arrangements whereby a company that was part of a cartel is offered immunity for assisting with an investigation. Contrast this with the absence of protection for those in the supply or value chain who are well positioned to blow the whistle but are afraid of victimisation.1 This illustrates the need for more active and meaningful intervention, including through more stringent legislation. We note with concern that the Competition Amendment Act of 2009 has yet to be brought into operation, although it would have addressed some (but not all) concerns by enabling the Competition Commission to conduct market inquiries and ascribing personal criminal liability for directors who engage in anti-competitive conduct. We are calling on the Committee to enquire into why the Act has not been brought into operation. Further we note that the State President in his 2011 “State of the Nation Address” indicated that there would be the likelihood of legislative reforms “to strengthen the Competition Act to open the market to new participants”. We believe that before this undertaken there is a need for an intensive discussion with stakeholders, including through NEDLAC, on the type of investment and foreign direct investment that we should be encouraging. Any amendments should take this into account. 1 In the bread price fixing scandal, the whistle was blown by a small independent bread distributor who claimed that afterwards one of the bread producers refused to continue providing him with stock. 5 1.2 On Public Interest Generally The approval of this merger has highlighted the fact that the Competition Act does require that certain public interest considerations be taken into account when considering a potential merger. The Tribunal is of the view that the public interest concerns raised by our affiliates (SACCAWU, SACTWU, NUMSA and FAWU) are adequately addressed through the imposition of certain minimal conditions. Here the Tribunal stressed its limited jurisdiction in relation to public interest considerations. While we argue that it nevertheless construed its jurisdiction and the public interest considerations themselves too narrowly in this case, we would agree that the list of public interest considerations in the Competition Act is too short and should be broadened to include the following: Any health and safety standards or concerns that may be associated with operations of the merged business entity, as well as each merger applicant’s history or track record History of compliance with labour standards and collective agreements Any environmental standards or concerns that may be associated with operations of the merged business entity, as well as each merger applicant’s history or track record Food security Security of supply and the development of local industrial and manufacturing capacity The factors above have been proposed after careful consideration of illustrative evidence in relation to Walmart and retailers abusing their dominant position in the market to drive down producer prices and impose various other operational, technical and product specifications, which have at times produced a range of serious adverse consequences for suppliers, workers, consumers and even the general public. Where companies merge they should be expected to conduct themselves responsibly. Competition authorities need to assess whether such mergers increase market power to such an extent that the consequences of abuse extend beyond merely contradicting competition law objectives. 6 Downward pricing pressure by retailers on the supply chain has been known in turn to place downward pressure on wage bargaining and other employment conditions in sectors other than retail continue to reap the benefits of their ever increasing margins. However, Walmart has been known to be over-whelmingly more effective than any other retailer in exerting complete control and dominance over suppliers’ operations and the value as a whole. Practically this has different implications for different sectors and products. However, those engaged in the production of perishable products, especially agrifood, are considerable more vulnerable owing to the limited time available for them to off load their products. Often suppliers trying to increase margins by cutting down on costs associated with environmental, health and safety standards. 2 SPECIFIC COMMENTS ON THE TRIBUNAL’S ORDER As we noted earlier it is our view that that the Tribunal erred in its decision, and appears to have not applied its mind to key substantive arguments raised by COSATU affiliates in the proceedings. 2.1 On the Relevant Market and the Impact on Competition Paragraph 26 of the Tribunal’s “Reasons for Decisions” states: “It is common cause that this merger raises no competition concerns”. (emphasis added) The general legal meaning and usage of the phrase “common cause” would convey the message that an issue is accepted as true and is uncontested by all parties. However, this is completely incorrect as affiliate documentation had identified extensive concerns that the merger would lead to uncompetitive outcomes both in 7 relation to the retail sector and its supply chain. Disregarding this fact the Tribunal document goes on to state further: “Walmart does not compete with Massmart in South Africa”…. In light of the above we find that the transaction would not substantially prevent or lessen competition in any of the markets that Massmart operates”. On this superficial basis the Tribunal then completely dispensed with the requirement in terms of Section 12A(1) of the Competition Act to determine whether the merger would substantially prevent or lessen competition. Section 12A(2) lists a number of factors that must be taken into consideration when making this determination such as the “level and trends of concentration, and history of collusion in the market” and “the nature and extent of vertical integration in the market”. None of these are even mentioned in the Tribunal’s reasons for its decision. Whereas the Tribunal noted that the retail sector is already highly concentrated. The question that arises is then is to what extent will an entity, that is the largest global retailer and largest retail grocer in the USA, just contribute to even further concentration in the retail sector. Note in 1999 Carrefour and Promodès, two French groups, merged to become the biggest retail group in Europe and second in the world after Walmart. This is largely considered to be in response to Walmart’s acquisition of ASDA, the No. 3 retailer in the UK.2 It is relevant there are already indications that Pick n Pay and Tesco (UK retailer) are in the process of discussing a potential merger. 2.1.1 Vertical Integration Further both globally and locally there has been increased consolidation and integration vertically in the supply chain, as suppliers face increasing downward 2 See Enrico Colla and Marc Dupuis Research and managerial issues on global retail competition: Carrefour/Walmart in the International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, Volume 30, 200, p 104. 8 pressure on their prices from retailers who wield excessive bargaining power. However, suppliers are dependent on retailers for access to markets for sale of their goods. Thus increased concentration in the supply chain especially in the agri-food sector has been the result in response to this challenge. Farmers have tended to be the biggest losers with them receiving progressively less of the proportionate share of revenue associated with consumer spending.3 In the USA this can be illustrated by considering the distribution of the share of the consumer dollar spent on beef. In 1990 it was distributed as follows: $, 59 for the farmer, $.08 for the packer and packinghouse worker, and $,33 for the retailer. By 2009 this had significantly altered to $,42, $,09 and $,49 respectively. 4 It should be noted that the Food Pricing Monitoring Committee (FPMC)released a report in 2003, which in confirming very similar trends locally noted the: “Substantial evidence of oligopolistic behaviour and monopolistic competition in the food sector. Increasing concentration in the food value chain is a global trend, …The competition is fierce, and based on economies of scale, small margins but high volumes, and fast turnover. This structure makes it very difficult for smaller players to enter the market, either as retailers, or as food processors and distributors. In response to this the FPMC made the following recommendation: “An important intervention by the State would be to increase participation and competition in the market by reducing barriers to entry for smaller suppliers, manufacturers and retailers. Innovative programmes under the Black Economic Empowerment programme (BEE), such as preferential procurement systems, can be used effectively to promote increased participation. Government will, however, have to look at programmes to assist such new entrants with startup capital”. The Tribunal’s order appears to make little effort to address the above. Contrary to the emphasis above on promoting smaller suppliers, manufacturers and retailers and 3 International Federation of Agricultural Producetrs, Industrial Concentration in the Agri-food Sector, May 2002, p.3. 4 UFCW (United Food and Commercial Workers) Ending Walmart’s Rural Stranglehold 2010, p3. 9 BEE, the Tribunal states that the displacement of small businesses in this case would be “inevitable consequence of the competitive process”5. This ignores the fact that the promotion of HDIs and small businesses would promote both public interest objectives and address concentration in the retail sector. Instead the tribunal opted for a result that profoundly undermines competitiveness and increases the barriers for small businesses. 2.2 Public Interest Demands 2.2.1 On Retrenchments, Labour Matters and Collective Bargaining We remain completely opposed to this merger notwithstanding the decision of the Tribunal. We note that SACCAWU, whilst maintaining this opposition, tabled alternative demands to be considered in the event that the merger was approved. Many of these sought to mitigate to adverse implications for labour rights and collective bargaining. However, the response of the Tribunal was to impose in very minimalist form those conditions that the merging companies offered to undertake. These include: The imposition of a two year moratorium on “merger-specific” retrenchments, although SACCAWU had asked for three years. Considering that little emphasis was given to the fact that 503 workers were retrenched in June 2010 a mere three months before the intention to merge was announced but long after confidential merger discussions had been initiated between the two parties, it is likely that the interpretation of what is ‘merger-specific” would be construed very narrowly. “Preference” would be given to the reemployment of the 503 employees referred to above. This falls significantly short of the demand for reinstatement and the reference to “preference” would not necessarily prevent the organisation from merely going through the motions. 5 See Tribunal statement on the conditional approval of the merger between Wal-mart Stores Inc. and Massmart Holdings Limited – 31 May 2011, p2. 10 SACCAWU’s current status as the largest representative union is to be recognised for three years and existing labour agreements would be honoured. This would produce minimal impact taking into account Massmart’s own adverse record, which include refusing to bargain centrally, the provision of low wage and poor working conditions with little job security. 2.3 On Procurement The Tribunal has refused to accede to the call for the imposition of mandatory minimum quotas for procurement of local content, which would have afforded local industries some protection against the flooding of our market of cheap imported goods. Many of our manufacturing sectors are already under severe pressure with the range and volume of imported and subsidised goods that are cheaper than locally produced ones. Walmart with its unmatched global buying power and ability to source cheap goods poses an unprecedented risk to local industry. Invariably this would pressure other retailers to respond in kind by increasing reliance on imports at the expense of local job creation. The Tribunal was of the view that a quota on the procurement of local content would constitute discriminatory treatment as other retailers would not have to comply with such a requirement. However, this ignores the principle that equal treatment can create discriminatory effects if all were not equal to start with. Walmart is not only the largest global retailer but it is also bigger than the next four global retailers combined, and has an annual revenue in excess of $400 billion. We note that the merged entity has pledged to establish a programme aimed at the development of local South African suppliers, including SMMEs, which will be funded to the amount of R100 million. In principle we believe that appropriate investments into our economy must be encouraged. However, we believe that serious questions need to be asked about the nature of this investment. It is clear that this programme is intended to have an exclusive relationship with Walmart globally and the local merged company. In other words these are not intended to be independent suppliers in the value chain. Their existence and survival will likely depend on 11 Walmart, which has produced disastrous results elsewhere including in respect of health and safety. The nature of the programme suggests a co-ordinated initiative to effect a vertically integrated structure within supply chain that has received the blessing of the Tribunal, but which would have done better to enquire into the potential anti-competitiveness this would create. 12