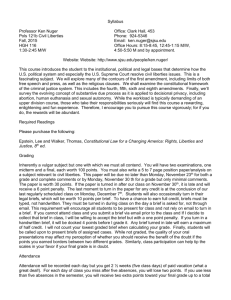

ConLaw1st_Feldman_F2009 – Outline

advertisement