review of the professor james houghton paper on slavery

advertisement

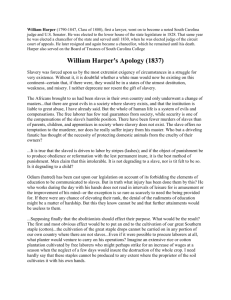

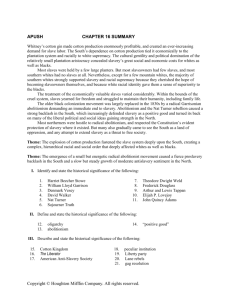

Slavery A paper delivered by Professor James Houghton of George Washington University, Washington DC and The Smithsonian Institution at Liverpool John Moores University, on Thursday 23 March 2000. Reviewed By Clare Horrocks, Edge Hill College Looking at the misunderstandings and mythology surrounding discourses of slavery, this paper was delivered to American Studies students following a course entitled ‘Black Atlantic’. However, as with many of the projects undertaken by the American Studies Centre, there were also a number of other visitors who were not students at the university. It was a friendly and informal afternoon enjoyed by all. Contextualised within the eighteenth and nineteenth century, it was a paper which sought to explore how the legacy of slavery can be seen to provide a foundation for many of the concepts surrounding race in modern society. Professor Houghton undermined the myths that slavery only existed from the 1840s until its cessation in 1865, drawing out a history of oppression, richly supplemented by OHPs of charts and maps, tables and statistics which corroborated the continual oppression of black American slaves. Yet despite this extended history of slavery in America’s history, Americans today, he argues, are loath to directly refer to the term ‘slavery’. From direct experience, conveyed through a number of anecdotes, he exemplified how this tendency continues to persist today. Taking Thomas Jefferson as an example of how idyllic myths are formed, he proposed to the students that there was a vital contradiction in the representation of a man who wrote the Declaration of Independence, advocating “life, liberty and pursuit of happiness”, when he was in actual fact a slave owner himself. Jefferson was raised at Monticello, Virginia, where there is now a booming tourist industry with plantation tours and actors dressed in colonial costume. There is a history behind the family home which is shared by both the Jeffersons and the numerous slaves who worked there, yet tour guides fail to acknowledge their existence, even when directly questioned. There is a discourse of slavery which is hidden, Professor Houghton argues, behind the embarrassment of a nation which is still trying to accept that it is this history of oppression which lies behind many of the problems of race today. What was particularly interesting was his discussion of the divide between North and South and the distribution of industries which facilitated the slave/master relationship. Many people associate the slave trade with sugar and cotton plantations, but this was not the only industry in which slaves were employed. In the eighteenth century many Northern states like Virginia were involved with slaves and there was certainly no cotton or sugar in these regions! Their trade was tobacco, grown around the Chesapeake Bay and the colony of Maryland. Down in the Carolinas slaves were used in the production and growth of rice. It is only as we shift into the nineteenth century that we see a shift in trade and subsequently the occupations of the slaves. With growth came a shift in geographical location down into the Deep South, into a climate which facilitated the growth of cotton. By 1850 cotton constituted 57.5% of all US exports, as opposed to only 7.1% in 1800. Despite the decline in the slave trade in the Northern states after 1808, many of the buildings and institutions which still exist today, have been founded on the money derived from the slave trade, a legacy of their involvement; buildings such as Brown University, Rhode Island. To conclude, Professor Houghton reinforced how when one starts to talk about slavery, we reveal a whole group of inconsistencies in its depiction. Yet slavery’s legacy is still very much with us, playing a part in our living history, reminding us that we must take account of the human impact it had, and still has, on many Americans. Plantations re-enacting and role playing the segregation and oppression forget that they are reawakening memories which stimulate emotions of anger, hostility and sadness. We must not forget the history of this race of people, learn not to be afraid to stand up and acknowledge discourses of slavery, for it is their legacy which continues to provide the foundation for today’s concept of race. **** A stimulating paper which prompted many questions from both students and staff alike, may we extend our thanks to Professor Houghton and his partner Dr Lois Houghton and wish them a safe journey back to Washington.