Public Women, Private Men

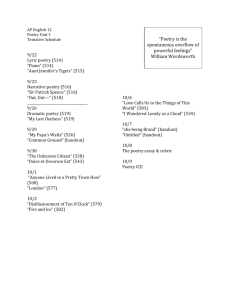

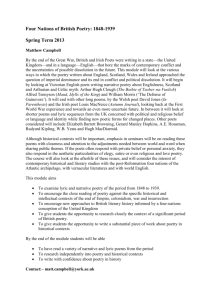

advertisement