Casablanca

advertisement

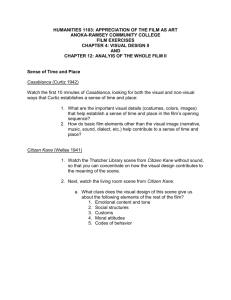

Harrison Potter HONR 101 Casablanca Essay 9/24/04 Casablanca came out in 1942 amongst little fanfare and with few expectations at the box office. As only one of the many films that its actors were working on at the time it didn’t particularly stand out in any respect; however, through a combination of good fortune, excellent casting, and a subtly captivating plot it has come to be one of the most popular, widely-renowned, and oft-quoted films in history. One of the reasons for the film’s excellence in every respect is that it was directed by the very capable and dedicated Michael Curtiz. Aided by a masterfully written script drafted by Julius J. Epstein, Philip G. Epstein, and Howard Koch, he managed to “show that Rick, Ilsa, and the others lived in a complex time and place” (Ebert). When taken in combination with Humphrey Bogart’s classic portrayal of the cynical, yet virtuous, betrayed lover, Ingrid Bergman’s role as the ambivalent lover torn between two men, and the unrivaled casting of the numerous minor roles, Casablanca managed to earn recognition even in its own time, winning the Best Picture Oscar, as well as the Best Screenplay Oscar and the Best Director Oscar for 1943. Add to that impressive resume eight Academy Award Nominations and there is little room left to doubt the film’s greatness (Berardinelli). All that is left to do is to analyze why it is so critically acclaimed. Set in the midst of the busy Moroccan city of Casablanca during World War Two, Casablanca begins by providing some historical background. Following the German invasion and occupation of France many Europeans were desperately looking for a way out of Europe so that they might avoid the coming devastation. One of the few routes to the relative safety of America was through Casablanca, Morocco to Lisbon, Portugal, where safe passage to America could be found. The journey to Casablanca from mainland Europe was treacherous in its own right, but, as the final step out of territory under German influence, obtaining the coveted right of passage from Casablanca to Lisbon was fraught with danger due to the desperation of the many refugees. Germany also used its influence as a rising military power to pressure the existing French government in Morocco into being wary when giving out letters off passage, further increasing the difficulty of escape. Amidst such a tense and delicate atmosphere former American Rick Blaine, played by Humphrey Bogart, establishes himself as the owner of the renowned “Café Americain.” One of his acquaintances, Guillermo Ugarte, played by Peter Lorre, murders a pair of German soldiers in order to steal two irrevocable letters of passage which would be invaluable to anyone hoping to escape the purgatory that is Casablanca. Knowing full well that if he is apprehended for his crimes he will be caught that very night, Ugarte entrusts Rick with the letters of passage for the evening. Soon afterwards the police arrest Ugarte, leaving Rick in permanent possession of the priceless letters of passage. Later on that evening the intended recipients of those letters arrive at Rick’s café. To Rick’s great surprise not only is Victor Laszlo, played by Paul Henreid, amongst them, but the second intended recipient is Ilsa Lund Laszlo, Rick’s old lover from his time in Paris who abandoned him, played by Ingrid Bergman. Summoned into her presence by Sam’s rendition of “As Time Goes By”, Rick quickly becomes overwhelmed with the emotions which come flooding forth from the darkest dungeons of his heart. This leads him to drown his sorrows with alcohol later on that evening while recalling his experiences in Paris with Ilsa in the form of a flashback; meanwhile, in the background, Sam, played by Dooley Wilson, plays their song once more. Following Rick’s romantic recollection of his relationship with Ilsa in Paris, which informs the viewers of the emotional history behind the plot, the Laszlos begin to seek the letters of passage which they need in order to escape and continue their lives, and Victor’s leadership of the resistance, abroad. They soon discover that Major Heinrich Strasser of Germany, played by Conrad Veidt, has forbidden Captain Louis Renault, a Frenchman played by Claude Rains, to allow Victor Laszlo to escape Casablanca. Ilsa refuses to leave without him, even when Signor Ferrari, played by Sydney Greenstreet, offers to provide her with a ticket, although even he cannot risk granting Victor safe passage to Lisbon. This leaves them both trapped in Casablanca, helpless at the hands of the powers that be. While searching for a way to escape Victor learns of a local resistance meeting. As a leader of the movement he is obligated to attend the meeting. While he is gone Ilsa takes it upon herself to attempt to force Rick to relinquish the letters of passage which they so desperately need. Even going so far as to draw a gun upon him, in the end she still loves Rick to much to kill him, even to fulfill such a pressing need. Instead she begs him to think for the both of them, leaving her own fate and the fate of Victor Laszlo and all those who depend upon him in Rick’s hands. Soon after Ilsa’s encounter with Rick, Victor is imprisoned for causing trouble at the Café Americain by leading everyone in singing “La Marseillaise”. Rick’s café is also shut down in the process and he is forced to address the pressing problem that Victor Laszlo’s continued presence poses. After much careful thought he manages to come up with a scheme that will not only grant the Laszlos their freedom, but also kill off the troublesome Major Heinrich Strasser. After convincing Renault to release Victor on the grounds that he will later trick him into accepting the letters of passage, thereby framing Victor for the murder of the German couriers, Rick forces Renault at gunpoint to sign the letters and let them go. In the process, however, Rick also gives Renault the chance to summon Strasser to the scene. When the Major arrives at the airport as the Laszlos are escaping Rick shoots him before he is able to call for reinforcements. Captain Renault then takes advantage of the opportunity to tell his men to “round up the usual suspects,” freeing himself to join Rick in aiding the underground resistance movement (Casablanca). Having sacrificed his love for Ilsa in order to contribute to the greater good of the resistance movement Rick is free to walk away with his companion, Captain Renault, into the night. French culture and history are also displayed throughout Casablanca. From the traditional courtly romance between Rick and Ilsa in Paris to the chivalrous way in which Rick sacrifices his one true love for the greater good of the world, French influences on the film cannot be ignored. Indeed, the whole film is set in French Morocco. At one point in the film Victor even leads the crowd of Frenchmen in Rick’s café in singing “La Marseillaise.” French nationalism, including the French underground resistance, is also represented in the film. The German invasion of Paris is also portrayed in the film as part of Rick’s flashback. Even in the midst of the film’s climactic ending the Vichy government’s role in France during the period and the resentment many felt towards it are symbolically represented when Renault discards the bottle of Vichy water to follow Rick. Such an epic tale of a betrayed love being renewed only to be willingly sacrificed by the lovers for a higher cause has rightfully burrowed itself into the hearts of millions of moviegoers the world round; accordingly, many movie reviews have been written on the film. Roger Ebert proceeds in his review to analyze what aspects of the film made it such a successful presentation of an endearing tale. The summation of his thorough analysis is that the plot is merely a “trifle to hang the emotions on” and that nothing during production indicated that a classic was being born; however, thanks to its wonderfully witty humor, impeccable casting, and the subtle emotion that permeates its entirety, Casablanca is a film that “gains resonance” through repeated viewings, the mark of a film of true quality (Ebert). Berardinelli similarly applauds the film, claiming that it is “America’s best-loved movie”; however, he focuses on slightly different aspects of the film’s genius. Berardinelli stresses that Casablanca has remained popular for so many years because its core values are timeless, pronouncing that “the themes of valor, sacrifice, and heroism still ring true.” Additionally, the characters are all so very complex that they seem to be all the more real for their subtleties. Claude Rains is also praised for “standing out in nearly every scene” as an excellent Captain Renault. Berardinelli’s final compliment is that Casablanca doesn’t give in to “commonly held perceptions of crowd-pleasing tactics” (Berardinelli). I fully agree with the praises with which the two reviews credit Casablanca. Rather than further elucidate all of the technical accolades that they delineate, I will simply include my own personal intuitive reaction to the film in general. I found the love triangle at the center of the story to be believable, though a little over the top at times. I was especially taken aback by Ilsa’s remark that Rick should think for the both of them. Modern society emphasizes the woman’s role as an equal in any healthy relationship, yet Ilsa seemed to be more enamored with the greatness of each of her lovers than she seemed to truly love them as a potentially lifelong companion. Each of the two men seemed to be the foundation upon which the relationship rested, one man a great leader, the other a great personality, and it seemed that should either man suddenly become a normal lover she would no longer love him. As the vast majority of relationships, particularly successful relationships, develop between ordinary people, I doubt that such hero worship can sustain a permanent bond between any two individuals. Rick’s choice at the conclusion of the film constituted a fair ending because although he did not want to give up Ilsa, he recognized that if she stayed with him she would eventually regret it; she would ultimately be happier with Victor. Another aspect of the movie that I thoroughly enjoyed was that almost every line that Rick spoke throughout the entire movie was memorable or witty. Ultimately I found no significant flaws with the movie’s believability emotionally, although it was hard to believe that for such a man as Victor there was no other way out of Casablanca than on a plane with letters of passage. This minor detail did not hinder the flow of the movie, however, and did not detract from its poignancy. Overall I give it a solid 2 thumbs up. Casablanca is undoubtedly a film for the ages. Effortlessly incorporating love, romance, virtue, sacrifice, war, hope, cynicism, and a witty humor unlike any other, it stands alone as a reminder of the artful delicacy and captivating emotion that stood as the foundation of cinematography before the advent of modern special effects. As it cannot resort to superfluous ostentation in order to conceal plot manipulation or banality, as do so many of the films of the 21st Century, it instead establishes as its foundation an incomparably poignant and intricate plot centered around characters who are both round and sympathetic, thereby capturing and maintaining the attention of the audience for its entire duration. Harrison Potter Works Cited Berardinelli, James. “Casablanca.” Top 100 All-Time. 1998. 26 Sept. 2004 <http://movie-reviews.colossus.net/movies/c/casablanca.html>. Casablanca. Dir. Michael Cutriz. Perf. Humphrey Bogart, Ingrid Bergman, Claude Rains, and Paul Henreid. Warner Brothers, 1942. Ebert, Roger. “Casablanca.” SunTimes.com. 1999. Chicago Sun-Times. 26 Sept. 2004 <http://www.suntimes.com/ebert/ebert_reviews/1999/01/blanca1001.html>.