45. Currency and the Populist Movement.doc

advertisement

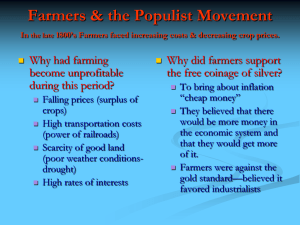

Currency and the Populist Movement After the United States permanently adopted a true national currency with the greenbacks generated to fund the Civil War, debates about our monetary system became so complex only a handful of congressmen understood what they were voting about. The tariff also remained a controversial issue. While Americans universally believed a tariff was necessary, both Republicans and Democrats in states above the Mason-Dixon Line supported a high protective tariff. Southern Democrats and liberal Republicans wanted those tariff rates lowered. A similar division occurred over the currency. These debates necessarily involved American farmers in protests about things they little understood. What they believed, however, made them angry. America’s most successful third-party movement, the Populist Movement, arose from their dissatisfaction as the world changed around them. Remember, a main goal after the Civil War was to establish the paper money of the United States on firmer ground. Farmers, however, wanted to go right on with increasingly worthless paper money because they were deep in debt. Inflation resulting from a weak dollar would not only help them make “more” money for their crops, they would be paying off their debts with “cheaper” money. The amount they borrowed did not change, but the value of the dollars their creditors received in payment was slipping. Creditors therefore sought to return America to hard money policies linked to gold, a process that would produce “contraction” or deflation as opposed to inflation. The Panic of 1873, however, seemed to call for inflationary policies. Some economic analysts also called for what became known as the Ohio Idea, the notion that the US government should pay its national debt with its own greenbacks rather than with gold. The merest mention of such an idea increases inflation, and indulging in it too much creates hyper-inflation such as that which would destroy the economy of Germany after World War I and of nearly every Latin American republic during the 20th century. President Ulysses S. Grant refused to surrender, though, and he favored the Gold Standard. His Resumption Act provided that after January 1, 1879 Americans would be able to walk into banks and “redeem” paper money in gold coin. This measure was achieved by compromising with the West by permitting new branches of the National Bank to open more easily there where farmers could thus be provided with more cash flow. Simultaneous to this debate in Washington, D. C. was the birth of a farmers’ organization called the Patrons of Husbandry. Oliver Hudson Kelley began this organization, also called the Grange, in 1867. Kelley wanted farmers to experience a solidarity similar to that of the Knights of Labor through lectures, debates, picnics, barn singin’s, etc. The Grange was divided into local units where men and women became equal members. By 1868 there were only ten chapters, but by 1875 800,000 farmers from across the Midwest and the South had joined. The Grange kept its social and intellectual themes but gradually expanded to discuss economics and, yes, politics. Officially the Grange forbade its members to talk about politics but the end of the meetings turned into mini-conventions. The price of wheat was down; the price of railroad transportation to market was up. It took the value of one bushel of wheat or of corn to pay to transport another bushel to the East. Grangers also decried the middle men who owned grain elevators, giant silos used to store crops as they waited for the trains. The grain elevator owners offered a lowerthan-market price, but when a farmer arrived with his crop in a wagon he was forced to accept the price or face ruin. The dearth of National Bank branches in the West meant fewer loans and little money. Railroads also gave rebates, as we have seen, to long shippers of great volume, and farmers could not understand how it was cheaper to send oil long distances than it was to ship grain short distances. Some states in the West fixed prices for grain elevators and railroads, and in Munn v. Illinois the Supreme Court said they could do so. All the while the machine age promised prosperity, but few agricultural or industrial workers got what was promised. By 1880 80% of US wheat was harvested by machine (the McCormick Reaper) six times faster than by hand. Production was up so high that markets were glutted and prices plummeted. Farmers expanded onto the TransMississippi prairie where a huge clash of cultures was ignited. Indians, including the Apache, Hopi, Comanche, Sioux, Blackfeet, Nez Perce, and Cheyenne were forced onto reservations by 1890. This year saw the last Indian “uprising” at Wounded Knee, South Dakota where 200 Indian men, women, and children were slaughtered after a misunderstanding in response to the Ghost Dance. The Ghost Dance was a revival of Indian religion in which warriors became convinced that their coats became impervious to bullets after dancing the Ghost Dance. At Wounded Knee the bullets went right through, especially when fired from Gatling guns. The final pacification of the Plains Indians opened up huge new lands for cultivation of the new crop alfalfa and then corn and wheat. Miners also experienced a clash as independent outfits were replaced by huge commercial operations. Cattle ranchers’ herds were decimated by a severe blizzard in 1886. The snow came so fast that cattle facing into the wind were simply suffocated. Cattle facing the other direction found their feet frozen to the ground, and many starved to death. Those cattle that survived lost ears and tails due to frostbite. Even future President Theodore Roosevelt’s ranch investment was a total loss. The invention of barbed wire in 1873 ended open grazing as farmers fenced their new claims. The long drives were over. The farmers found themselves a part of a vicious cycle. They ignored John Wesley Powell’s warnings from the U. S. Geological Survey that “factory-style” farms with the capacity to irrigate their crops were the only ones with a chance. He predicted that a few giants would control agricultural wealth as conglomerates would snatch up the 414 million acres of land available. His prediction largely came true but not until after the Great Depression. The first farmers in the West became victims of their own success. More and more US grain was produced until it fed everyone in cities in the East by 1874. Soon, US farmers were feeding people in European cities. Incredibly, US production became so pronounced that American grain was cheaper after shipping across the Atlantic than grain produced in Europe. This turn of events ruined European farmers who, of course, migrated to American cities and filled factories (while eating US grain). As this cycle made one revolution, American farmers forgot everything they learned about the South and the Cotton Kingdom in their A. P. US History classrooms and committed themselves to a cash crop economy. Without diversification, they became slaves to the market price of wheat and corn which they had driven lower by working harder. In 1881, a bushel of wheat sold for $1.19 and a bushel of corn for 63¢. By 1894, prices had dropped to 49¢ for wheat and 18¢ for corn. Farmers found themselves buying manufactured goods at tariff-bolstered prices while selling crops in an unregulated market. Farmers worked harder and grew more but earned less. To try to earn more they borrowed money to purchase new machinery to boost their production thereby flooding the market even more! All the while they were encouraged to blame their problems on the limited supply of currency by the Grange. By 1880, the Grange was divided into the Southern Alliance in the South and the Northern Alliance on the plains and had over 1 million members. The formerly non-political Grange opposed trusts, formed cooperatives, and pushed for cheap money (inflation). Out of these political impulses came the formation of the Populist Party in Omaha, Nebraska in 1891. Quixotic speakers like William Jennings Bryan wooed farmers with statements like, “Cities can be burned down and rebuilt; ruin farms and all the cities will have grass in their streets within a month!” Populists ran a presidential candidate, Civil War General James B. Weaver, by 1892 but then made their party irrelevant by the Election of 1896. Furthermore, prosperity appeared again for farmers not as a result of politics but European markets that grew again beginning in 1910. Corn went back up to 52¢ and wheat to 91¢ per bushel. We’ll have to trace the political demise of the Populist Party, but their longestlasting contribution was the idea of the farmers’ cooperative. They organized the farms of each county to be able to function like a corporation or trust. Cooperatives were monopolies that held crops off the market and collectively purchased facilities like grain elevators. Populists preached that farmers were raising, “Not crops but money.” Out of the Populist Movement came an effective lobby group that hired experts in a bureaucracy giving each county in America an agricultural agent. The notion of “agribusiness” was coined along with the term. A man named Hamlin Garland rose up to revive Populism but became disillusioned when all he accomplished was a 1908 drive to revive interest in country life with the Country Life Commission. The political power of Populism was crippled in 1896 and disappeared from American life with the prosperity of 1910. Populism remains the most successful third-party initiative in American history, however, so we should analyze it in detail, especially if you ever want to start a third party. Populism was a religious movement. Populists were among the most successful people in US history to combine Protestant Christianity and patriotism to make a powerful political force. They wielded that force in an attempt to rid government of the abomination of corruption as they saw it, and we use the term “grassroots” in American political rhetoric because this first “grassroots” movement came off the Great Plains (where there is grass). Populists viewed top-down reform movements like the push for civil service reform as failures, so they mobilized from the bottom up to recover a lost sense of community, pre-industrial societal unity, and old-time values. They believed they were ushering in a “Golden Age of the Golden Rule” as they rejected modernity. Among their ranks were some Greenback Labor Party adherents and some (but few) laborers. Among their collective values were anti-corruption political and social reforms, cheap money, anti-monopoly, and anti-Wall Street (which they viewed as a vast conspiracy against them). They were in sympathy with the urban Social Gospel movement we will study later and believed like the Social Gospelites that they were applying the ethics of the New Testament to American reform. Populists wanted to overcome post-war sectionalism and did get the farmers of the South to unite with the farmers of the West. Both types of farmers had problems. The Southern Alliance was filled with tenant farmers, an inherently powerless class. The Northern Alliance was filled with farmers blind to the fact that their own overproduction was ruining their markets. A bizarre reality was the sight of wagon trains going back East! From 1880-1890 18,000 wagons filled with failed homesteaders headed back to the cities. I wonder what they did with the wagons. Would you buy a used wagon from a failed homesteader on your way out to claim your homestead? Wouldn’t you think twice about going? The grassroots movement of Populism offered new opportunities for women as members and as leaders. Female leaders included Sarah Emery, who wrote Populist tracts, and Annie Diggs, who channeled Protestant sentiment toward prohibition. Mary Lease was a fiery orator for the movement who is famous for having said, “Raise less corn and more hell!” At least she seemed to understand the problem. Women were inexperienced politically in America, of course, but so were farmers in general. The camp-meeting atmosphere of Populist rallies preached a new “promised land,” but Populists actually achieved none of their goals. The Populist Movement is therefore an American political tragedy (Shakespearean). They had a sweeping party platform that pitted their idea of true power (farms) against money power (cities). Their goals included federal government subsidies for farmers, a graduated income tax (punishing rich people), a flexible currency (eliminate the gold standard), the storage of surplus crops, the direct election of senators, laws to punish monopolies, laws to restrict immigration, and the nationalization (government takeover) of railroads. Their slogan of “The tramps vs. the millionaires” sounds a little “corny,” but do their ideas sound familiar? Are you aware that all of these ideas were eventually implemented except for the nationalization of railroads, and we even flirted with that one during World War I? Populist rhetoric fit into the general Protestant evangelical rhetoric about the coming millennium. Many American Christians interpreted widespread suffering as a sign of the coming Apocalypse. As Populist leaders went to and fro preaching about corn and hell, they carried around the writings of Thomas Jefferson and trumpeted his call for agrarianism. This affection for Jefferson is odd since he would have had little affection for the huge role the Populists were asking the federal government to take. They were the first Americans to ask the government to solve all their problems, and the big government of modern America was therefore their idea. As to their political success, it ranks as the best a third party has ever done, but that did not put General James B. Weaver in the presidency in 1892. A dozen congressmen were elected, however, and Populist governors were elected in Kansas, North Dakota, and Colorado. As we will see below, though, they sank their dreams in one basket made of silver which was carried by William Jennings Bryan, the Democrat running for president in 1896. Bryan championed the free coinage of silver. For all their hopes, the Populists fell prey to the genius of corporate America in that large silver mines had been looking for a large, disgruntled group of voters to mobilize as lobbyists to help with silver mines’ overproduction. The price of silver followed markets just like the price of grain. Let’s go back a bit to explain. Grover Cleveland had blamed the Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1891 for destabilizing the currency and thus the economy. The US had been committed, by yet another law from John Sherman, to buy 4.5 million ounces of silver per month, ultimately to be used as coin. This measure caused inflation and another gold rush, this time just to buy gold from dwindling US gold reserves. Cleveland fought to repeal the law and thereby alienated western farmers (and silver miners). Oddly, this Democratic president was the first to ask J. P. Morgan to bail out the country. Morgan used his wealth to help the US issue bonds for the purchase of gold. People who hated Morgan were therefore alienated even further from Cleveland. The Election of 1896 was unfortunately turned into a one-issue campaign. The Democrats wrestled at their convention with the question—Cleveland and gold or Bryan and silver? William Jennings Bryan belted out a revival sermon at the nominating convention that went down in US history as his “Cross of Gold Speech.” He ended the speech against the gold standard by saying, “You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns, you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold!” The convention went wild and nominated Bryan. Since the Populist Party had preached that the free coinage of silver would solve all their problems, they threw all their support behind Bryan and the Democrats. Even when the ratio of 16:1 for the coinage of silver to gold was adopted, the Populists invalidated their own party and threw in their lot with the Democrats. The Republicans answered with William McKinley. Each candidate delivered 900 speeches during the campaign. McKinley’s were delivered from his front porch in Canton, Ohio where the Republican Party shipped 750,000 people on 9,000 railroad cars to hear him. William Jennings Bryan became the prophet and revival preacher swearing to wipe away corruption and the tyranny of Money in a crusade of speaking engagements wherever his campaign train would carry him (the origin of the phrase, “Whistle-stop campaign”). William McKinley was the last Civil War officer to win the presidency. He was a product of the Ohio Republican political machine run by Mark Hanna who had groomed McKinley to protect the protective tariff as a Congressman and then as president. The speech he repeated 900 times expressed his version of the Golden Rule, “Live and let live.” This odd reversal of a pietistic Democrat crusading against evil and a tolerant Republican standing on the Gold Standard swept Catholics and Protestants, farmers and workers, businessmen, and bankers into the Republican Party. Four of the five crucial swing states voted for McKinley. McKinley took 7 million of the popular votes and 271 electoral votes from the East, the Midwest, California, and Oregon. Bryan’s 6.5 million popular votes came from Populist strongholds of the South and West but only garnered 176 electoral votes. Both parties learned modern keys to victory: efficient organization, skilled communication, flexible and sophisticated candidates, and, of course, money. As for the Populist Party, the one basket into which they had put their eggs was smashed. Bryan lost, and a third party that subsumes itself into one of the two main parties could not pull back out with any credibility. The Populists faded from American politics, but remember, their ideas did not. Populists failed, but another reform movement took their ideas and succeeded in breaking the traditional power structure.