Little Red Riding Hood, The Fairy, and Bluebeard with

advertisement

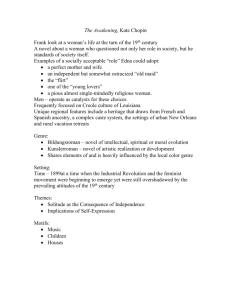

Little Red Riding Hood, The Fairy, and Bluebeard with Morals Edited with an introduction by Stephanie Stokes 1 Table of Contents Critical introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 Works cited page…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..12 Note on the text…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….13 “Little Red Riding Hood”………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..14 “The Fairy”…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….18 “Bluebeard”…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..22 2 Background “Little Red Riding Hood”, “The Fairy”, and “Bluebeard” are common tales, often viewed as fairy tales, in current cultures around the world. Most children grew up hearing the tales as bedtime stories and then passed them on to their own children. Originally, however, these stories weren’t meant for children. Frenchman Charles Perrault published “Little Red Riding Hood,” “Sleeping Beauty,” “Puss in Boots,” “Little Thumb,” “Cinderella,” “The Fairy,” “Blue Beard,” and “Riquet of the Tuft” in a collection entitled Tales of Mother Goose in 1697. Most of these stories are now commonly known as children’s fairy tales but at the time Perrault wrote the stories for, and about, Louis XIV’s French court. Charles Perrault was born in 1628 to a middle class lawyer. Even though his father’s status was low, Perrault quickly climbed up the ladder of wealth as an artist, essayist, and member of the French Academy. Gaining popularity in the French court Perrault became the administrator of King Louis XIV’s buildings and in 1672 he became the Academy’s first president. Perrault presented his first fairy tale to the Academy in 1691. Perrault passed away in 1703 but the last years of his life were devoted to writing the fairy tales which appeared in the Tales of Mother Goose. Over Perrault’s lifetime he wrote a fourvolume manifesto, multiple biographies, volumes of cultural criticism, comedies, and poetry but he is most remembered for his fairy tales (Orenstein 33). The fairy tales found in Tales of Mother Goose are modeled after the French court and the readers (those belonging to the court) would have known that based on the stories’ settings. An example would be Perrault’s “Bluebeard”, which told reminiscent stories of events held in the court. Bluebeard’s home was also described to look like the Palace of Versailles (Orenstein 34). Individually, the fairy tales each illustrated courtly morals and, just in case the reader did not understand that moral from the tale, Perrault included a rhyme at the end which told the lesson of the story. “Little Red Riding 3 Hood’s” rhyming moral warned young women to remain chaste (Orenstein 37). If the stories were read as a collection, they represented marriage at the time. Tales of Mother Goose, which was dedicated to King Louise XIV’s niece by Perrault’s son, was instantly a best seller. The collection continued to be a best seller until it was first revised in 1812 by German brothers Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. The Grimm brothers’ versions of Perrault’s tales are the most commonly known today. The 1812 revision of “Little Red Riding Hood” is the first to feature Little Red being saved from the wolf’s belly by a woodcutter, which is the version children know today. In Perrault’s original version the wolf ate Little Red and that was the end of the tale. Not only was the story revised by the Grimm brothers, but the moral was also changed. While Perrault’s version ultimately warned young girls that men were like wolves and that they should stay virgins, the Grimms’ version told lessons of not speaking to strangers and being obedient. Just as Perrault’s stories weren’t meant for children, neither were the Grimms’ stories. The original Grimm stories featured sex, pregnancy, violence, and gore. Edgar Taylor translated the Grimm stories from German to English in 1823 and they became popular among English children. Afterwards, the Grimm brothers edited their stories to be more fitting for children and took out the sex and pregnancy but left the gore and violence (Orenstein 52-54). Colonial Education The American colonies were extremely dependent on the mother country when they were first established. And many of the customs, cultures, and traditions that were practiced in the colonies were original to England. School was not one of the expectations. School systems were not originally standardized and many children learned from home or at a public or private institution. Much of the education also occurred in Sunday school at church. The schools in the colonies were also vastly 4 different; the New England colonies typically had more public schools for students to attend whereas the Southern colonies generally taught their children from home or church. In the New England and Middle colonies, the general school building was one room and housed all different grade and skill levels. Since schoolbooks were expensive they were shared among siblings and other students. One volume was often published with various different skill levels in it in order for that volume to be used by various students or by the same student for numerous years. In the home, parents even used the books in order to teach themselves. Since the books were used by so many students for such a great length of time they were often in bad condition. Many of the children’s literature from the colonial period cannot be found in print today or there are only a few copies in print due to the hard use of the books by colonial children (Lawrence ch. 3). The most popular books used in schools were readers and primers. Children first learned their alphabet and spelling, which they used a copybook for, and then moved onto studying essays, speeches, poetry, and sermons. The first ABC book and primer was published in 1591 and featured church sermons and elementary level ABC’s (Ford, 6). The primers and readers used in colonial schools were generally just British reprints. It wasn’t until after the American Revolution and the War of 1812 that American publishers began to make their own copies of schoolbooks, which encouraged parents and educators to support American authors (Gross and Kelly 300). Both English and American children books published in the colonial period were mostly done so anonymously, making it hard to find copies of the books today (Lawrence ch. 3). Schoolbooks not only taught academics but were encouragements for a child’s behavior and they often taught obedience, piety, patriotism, and cultural values. They were also geared towards Protestant the values of virtue, humility, duty, and temperance. After the American Revolution in 1785, the readers started stressing national ideals of natural rights, democracy, and republicanism (Gross and 5 Kelly 296). The children’s literature, although most of it was religious, also conveyed the social and cultural norms of the time period. A main focus of the literature was to teach children to “uphold the community through personal righteousness” (Lawrence ch. 3). The New England Primer and John Newbery The primer became famous in the colonies through the publication of the New England Primer. The predecessor to the New England Primer was the Protestant Tutor, which was published in 1686. There isn’t a known copy of this edition in print anywhere (Ford 15-16). Shortly after the Protestant Tutor was published, the New England Primer was first published. The first edition is believed to have been published between 1687 and 1690. The New England Primer, often referred to as the “Little Bible of New England” (Ford xvii), was the only schoolbook used for one hundred years and was reprinted and frequently used in conjunction with other schoolbooks for another one hundred years after its original publication. The primer taught millions through the use of the Bible. Each edition of the New England Primer was laid out in format similarly and included the same lessons. The first page of the New England Primer was a list of the alphabet, followed by repetitions of vowels, consonants, double letters, italicized letters, and capital letters. This was what students used to learn to read from. A page called the syllabarium followed the alphabet page. The syllabarium also assisted students in learning to read, starting with common two syllable combinations such as “ab”, “eb”, “ib”, “ob”, and “ub”. The syllabarium repeated this all the way up to six syllable words (Ford 23). An alphabet lesson followed the alphabet page and syllabarium. In the alphabet lesson, a moral Biblical story is told with each paragraph beginning with a successive capital letter of the alphabet (Ford 24). Following the alphabet lesson is probably the most famous of the New England Primer. This is an alphabetical rhyme accompanied by twenty-four pictures. The rhymes and pictures related to original sin, which was a strong religious belief of the Puritans (who would have been the ones mainly using the 6 New England Primer). The most edited part of the primer was the pictures and rhymes, due to the separation of England and the colonies after the American Revolution (Ford 25). Other important parts of the New England Primer included the Lord’s Prayer and Apostle’s Creed, a John Rogers poem, the Catechism which was either “Shorter Catechism” or “Spiritual Milk for Babes” depending on the edition, and a poem called “A Dialogue between Christ, Youth, and the Devil”. Other smaller pieces were included in the New England Primer, but those varied depending on which edition of the primer was being used. In Colonial America, children were normally not introduced to reading unless it was educational or Biblical readings. This started to change when works by John Newberry were introduced in the colonies. Newberry began working in England as an apprentice. When the owner of the shop he was apprenticing for passed away, Newberry took over and began to write children’s stories that were primarily for entertainment instead of education. The stories featured children as the main characters but were still religious (Monaghan 321). Perrault’s fairy tales would have more than likely been featured in later editions of the New England Primers. He also wrote educational works which included the Royal Battledore, an illustrated alphabet book, and a spelling book called The Infant Tutor. They soon entered the American colonies by way of ship and copies were sold in large numbers at busy ports. Newberry is considered the “originator” of children’s literature (Monaghan 322). Fairy Tales in Colonial Education In 1697, when Tales of Mother Goose was published, books were a luxury, so Perrault did not write many fairy tales and those that he did were only read by those in the court. The most common books of Perrault’s time were calendars, almanacs, prayer books, religious tracts, and ABC books. A century later chapbooks were beginning to be published and this was the first place that Perrault’s fairy tales appeared for a general audience. While the stories were translated to English earlier, they were 7 not brought to the American colonies until 1794. Perrault’s translated Tales of Mother Goose were published in the colonies by Peter Edes at that time. Three years later, a shorter collection of the Tales of Mother Goose was published in the colonies by John M’Culloch in Philadelphia. The shorter tales, which has been transcribed for you here, include “Little Red Riding Hood”, “The Fairy”, and “Bluebeard” with the attached morals. Prior to the 1800’s, children’s literature in the colonies fell into one of five categories: 1) religious writings and sermons, 2) primers and schoolbooks, 3) books, pamphlets, and essays on manners and behavior, 4) fiction and escapist novels, and 5) science and history books (Lawrence ch. 3). Fairy tales fit could easily fit into multiple of the categories ranging from primers and schoolbooks, fiction and escapist novels, and books, pamphlets, and essays on manners and behavior. While fairy tales could fit into any of these categories they did not find their way into the colonies until the 1750’s. While they entered the colonies in the 1750’s, children weren’t openly exposed to them until 1760. The main reason why fairy tales were not common in the colonies prior to the 1760’s was because they violated Protestant concepts, which therefore cause suspicion (Monaghan 318). According to Laura Kready, a fairy tale that is suitable for children must fall under one of the seven types of “classes”: 1) accumulative story, 2) animal tale, 3) humorous tale, 4) realistic tale, 5) romantic tale, 6) old tale, and 7) modern tale. An accumulative tale is repetitive in form (Kready 205). The repetition and rhythm found in an accumulative tale began as communal conditions in a community as a way to show expression and this formed folk tales, which were later transformed into fairy tales. The first accumulative tale was a Hebrew hymn that was sung during Passover. The hymn appeared in print for the first time in 1590. The repetition and rhythm found in the accumulative fairy tale is often used to teach phonics (Kready 206). 8 Charles Perrault’s fairy tales were not exempt from repetition. When they were published in the American colonies and used in schools, the repetition was more than likely used for phonics, a common strategy for teaching reading among younger students. In Perrault’s “Little Red Riding Hood”, there are multiple places in which repetition is used. The first repetition is presented to readers early in the text, when Little Red’s mother tells her to take her grandmother a custard and little pot of butter. That phrase, in variation, is repeated throughout the story; once when Little Red meets the wolf in the woods, once when the wolf was pretending to be Little Red and told grandmother what he had brought her, and once again when Little Red arrives at Grandmother’s house and tells “grandmother” (really the wolf) what she has brought her. The most known repetition found in “Little Red Riding Hood is at the end of the story in which Little Red gets into bed with the wolf, whom she believes to be her grandmother. The repetition, much like the one about the custard and pot of butter, are done in variation but the repeated part is “grand-mamma what great…you have!” Each line has a different body part mentioned by Little Red, ranging from arms, legs, and teeth. Each statement of repetition is answered with repetition by the wolf as well, in which he says “that is the better to…my dear”. Just as Little Red’s body parts were varied, so was the wolf’s answers. Other forms of repetition found in Perrault’s “Little Red Riding Hood” include the repetition of “tap, tap” every time a character knocks on a door, which is answered by “pull the bobin and the latch will go up”. While “Little Red Riding Hood” is full of repetition, Perrault’s “The Fairy” isn’t so much. The repetition is still present, but not as heavily as it is in “Little Red Riding Hood” or “Bluebeard” (which you will see in a moment) and it is not laid out as clearly as it is in either of the two other tales. “The Fairy” is a story of a mother who prefers one child over the other, although the child she prefers is ungracious and rude. As the story goes, the gracious child is rewarded by a fairy for being so kind and good while the ungracious, rude daughter is cursed by the same fairy. Perrault adds in subtle repetition through the 9 spoken words of the fairy, in which she asks twice for a drink and then twice states “I will give you a gift, that at every spoken word, there shall come out of your mouth a…”. “Bluebeard”, much like “Little Red Riding Hood”, is full of repetition. The only difference between the two is that the repetition in “Bluebeard” does not begin until about halfway through the story. Bluebeard’s poor wife and her sister have a call and answer for pages of the story, repeating the phrases “Anne, sister Anne, dost thou see anybody coming?” “I see a great dust coming on this side” “Are they my brothers?” “Alas! No dear sister, I see a flock of sheep”. Also continuing on for pages is a call and answer between Bluebeard and his wife, in which the repetition is “Will you not come down?” “One moment longer!”. Not only is conversation repeated over and over in “Bluebeard”, but so are actions. Repeatedly Bluebeard’s wife throws herself at Bluebeard’s feet, crying ad begging for her life and repeatedly Bluebeard denies her this request. Besides the repetition and phonics in Perrault’s fairy tales, these stories were probably used to teach children moral lessons and proper behavior in the colonial period. At the end of each of Perrault’s fairy tales he includes a rhyming moral, which are easy for children to remember due to their rhyming nature. The moral lesson of “Little Red Riding Hood” is that a young woman should stay chaste. When a lady lost her virginity in the 1600’s it was often said that the girl had “saw the wolf” (Orenstein 26) and the original woodcut for Perrault’s “Little Red Riding Hood” featured Little Red under bed covers with the wolf on top of her, suggesting that the story was about the loos of virginity. “The Fairy” has two moral lessons, one being that sweet discourse is of more value than money and jewels. The second lesson is that civil behavior is important in order to be rewarded for it. “Bluebeard” also had two moral lessons. The first lesson was about curiously being the death of you, while the second lesson was about husbands striking the fear into their wives. All of these would have been morals colonial schools would have taught their children. Even as the years progressed, these fairy tales were continued to be used in 10 schools. In 1901, the newspaper The Publisher’s Weekly published an article about Charles Perrault’s fairy tales and how they were being used in a manual for upper grammar grades. Over the years, the fairy tales began to be used less and less in schools and when they are used in schools today they are generally the Walt Disney version that most children know today. The most ironic part of Charles Perrault’s fairy tales comes from the facts that they were not originally meant for children, yet over the years the stories have been transformed into reading practice and moral lessons for children and as early as the 1930’s into the beloved children’s stories that are still being told to children as bedtime stories. 11 Works Cited Ford, Paul L. The New-England Primer: A History of its Origin and Development. New York, NY : Dodd, Mead and Company, 1897. Print Gross, Robert A., and Mary Kelley, eds. A History of the Book in America: An Extensive Republic Print, Culture, and Society in the New Nation 1790-1840. Volume 2. Chapel Hill , NC : The University of NC Press , 2010. Print. Kready, Laura F. A Study of Fairy Tales . Cambridge , MA : The Cambridge Press , 1916. Print Lawrence, Keith. "Social Dawnings: A Survey of American Moral Writings, 1600-1800." Diss. U of Southern California, 1987. Web. Monaghan, E. J. Learning to Read and Write in Colonial America. University of Massachusetts Press , 2005. Print. Orenstein, Catherine. Little Red Riding Hood Uncloaked: Sex, Morality, and the Evolution of a Fairy Tale. New York, NY : Basic Books, 2002. Print. Sever, Anne. The Publisher's Weekly [Boston , MA] 14 Dec. 1901, volume 60 part 2 : 1443. Print. 12 Note on the Text Little Red Riding-Hood, The Fairy, and Blue Beard; with Morals published in Philadelphia by John M’Culloch in 1797 was taken from the Early American Imprints, Series I: Evans, 1639-1800. The d’Alte A. Welch copy was used. No other texts were used when transcribing this document. While the stories do not have an “official” author they have been accredited to Charles Perrault over the years. Editorial changes that have been made are few. The elongated S has been changed to the standard S for easier reading and quotation marks have been added in when there is spoken dialogue to make readers aware that characters are speaking. The quotation marks were absent in the original copy. All other spelling and punctuation has been kept the same in order to preserve the original text which was used for educating children. 13 Little Red Riding-Hood Once upon a time there lived in a certain village, a little country girl, the prettiest creature ever was seen. Her mother was excessively fond of her; and her grandmother doated upon her much more. The good woman got made for her a little red riding hood1, which became the girl so extremely well, that everybody called her Little Red Riding-Hood. One day her mother having made some custards, said to her, “Go, my dear, and see how the grand-mamma does, for I hear she has been very ill. Carry her custard, and this little pot of butter”. Little Red Riding-Hood set out immediately to go to her grandmother, who lived in another village. As she was going thro’ the wood, she met with Gaffer Wolf, who had a very great mind to eat her up, but durit2 not, because of some faggot3 makers harn4 by in the forest. He asked her where she was going. The poor child who did not know that it was dangerous to stay and hear a Wolf talk, said to him, “I am going to see my grand mamma, and carry her a custard, and a little pot of butter, from my mamma”. “Does she live off?” said the Wolf. “Oh! Ay” answered little Red Riding-Hood, “it is beyond that mill you see there at the first house in the village”. “Well”, said the Wolfe, “and I’ll go and see her too; I’ll go this way, and you go that, we shall see who will be there soonest”. The Wolf began to run as fast as he could, taking the nearest way; and the little girl went the farthest about, diverting herself in gathering nuts, running after butterflies, and making nosegays5 of all the little flowers she met with. The Wolf was not long before he got to the old woman’s house. He 1 A hood with a cape or a short hooded cloak The editors best guess is that this word is some form of “dared” 3 A bundle of sticks; firewood 4 This is assumed to be a typo and the editor is guessing that the word should be “hard” whereas “hard by” means “near by” 5 A small bunch of flowers typically given as a gift. In the medieval times they were carried or worn around the head or bodice to mask unpleasant smells and literally keep the nose gay. Queen Victoria made them popular as a fashion accessory in 1837. 2 14 knocked at the door, tap, tap. “Who’s there?” “Your grand-child, Little Red Riding-Hood” replied the Wolf, counterfeiting her voice, “who has brought you a custard, and a little pot of butter, sent you by momma”. The good grand-mother, who was in bed, because she found herself somewhat ill, cried out, “Pull the bobin and the latch will go up”. The Wolf pulled the bobin, and the door opened, and then presently fest upon the good woman, and ate her up in a moment, for it was above three [ ]6 that he had not touched a bit. He then shut the door, and went into the grand-mother’s bed, expecting Little Red Riding-Hood, who came sometime after, and knocked at the door, tap, tap. “Who’s there?” Little Red Riding-Hood, hearing the big voice of the Wolf, was at first afraid: but believing her grand-mother to have got the cold, and was hoarse, answered, “Tis your grand-child, Little Red Riding-Hood, who has brought you a custard, and a little pot of butter, mamma sends you”. The Wolf cried out to her, softening his voice as much as he could, “Pull the bobin and the latch will go up”. Little Red Riding-Hood pulled the bobin, and the door opened. The Wolf seeing her come in, said to her, hiding himself under the bed clothes, “Put the custard and the little pot of butter upon the stool, and come and lie down by me”. Little Red Riding-Hood undressed herself and went into bed; where being greatly amazed to see how her grand-mother looked in her night clothes, said to her, “grand-mamma, what great arms you have got!” “That is the better to hug thee, my dear.” “Grand-mamma, what great legs you have got!” “That is to run the better, my child.” “Grand-mamma, what great teeth you have got!” “That is to eat thee up.” And upon saying these words, this wicked Wolf fell upon the Little Red Riding-Hood and ate her all up. 6 The text from the original copy is not legible 15 The Moral From this short story easily we discern, What conduct all young people ought to learn. But above all, young growing [ ]7 fair, Whose oriental rosy blossoms began t’ appear Whose beauties in the fragrant spring of age With pretty airs young hearts are apt t’ engage. Ill do they listen to all sorts of tongues, Since some enchant, and lure like Syren8 songs, No wonder therefore ‘tis, if overpower’d, So many of them has the Wolfe devour’d. The Wolf I say, for Wolves too sure there are Of every sort and of every character. Some of them mild and gentle humour’d be, Of noise and gall, and rancour9 wholly free Who, tame, familiar, full of complaisance; 7 The text from the original copy is not legible Referring to the Sirens in Greek mythology. They were three women, portrayed as seductresses who lured nearby sailors with their enchanting music and voices. 9 A feeling of deep and bitter anger and ill-will; resentment 8 16 Ogle and leer, languish, cajole and glance, With luring tongues, and language wondrous sweet. Follow young ladies as they walk the street, E’en to their very houses, nay, beside, Are artful, tho’ their true design they hide: Yet all these simp’ring tools, who does not see, Most dang’rous of all Wolves in fact to be. 17 The Fairy There was once upon a time, a widow who had two daughters. The eldest was so much like her in the face and humor, that whoever looked upon the daughter, saw the mother. They were both so disagreeable, and so proud, that there was no living with them. The youngest was the very picture of her father, for courtesy and sweetest of temper, was withal one of the most beautiful girls ever was seen. And people naturally love their own likeness10, this mother even doated on her eldest daughter, and at the same time had an horrible aversion to the youngest. She made her eat in the kitchen and work continually. Among other things, the poor child was forced twice a day to draw water above a mile and a half of the house, and bring home a pitcher full of it. One day as she was at this fountain, there came to her a poor woman, who begged of her to let her drink. “O, ay, with all my heart, goody” said this pretty [ ]11 girl, and rising immediately the pitcher, she took up some water from the clearest place of the fountain, and gave it to her, holding up the pitcher all the while, the she might drink the easier. The good woman having drank, said to her, “You are so very pretty, my o ar, to good and so mannerly, that I cannot help giving you a gift (for this was a fairy, who had taken the form of a poor country woman, to see how far the ordinary and good manners of this pretty girl would go), I will give you for a gift, the fairy, that every word you speak, there shall come out of your mouth, either a flower, or a jewel”. When this pretty little girl came home, her mother scolded her for staying so long at the fountain. “I beg your pardon, mamma” said the poor girl, “for not making more haste” and in speaking 10 This word is thought to say “likeness” but due to faded print in the original copy the editor is not 100% sure and has taken the liberty to make an educated guess based on context and print that can be read from the original 11 The text from the original copy is not legible 18 these words, there came out of her mouth two [ ]12, two pearls, and two diamonds. “What is it I see there?” said her mother, quite astonished. “I think I see pearls and diamonds come of the girls mouth! How happens this child?” (This was the first time she ever called her child). The poor creature told her frankly all the matter, not without dropping out infinite numbers of diamonds. “Truly”, said the mother, “must send my daughter thither. Come hither, daughter look what comes out of thy sisters mouth when she speaks! Would not you be glad my dear, to have the same gift given unto thee? Though hast nothing else to do but go and draw water out of the fountain, and when a certain poor woman asks you to let her drink, to give it to her very civilly”. “It would be a very fine sight indeed”, said this ill bred minx, “to see me go to draw water!” “You shall go hastily”, said the mother, “and that this minute”. So away she went, but grumbling all the way, taking with her the best silver tankard13 in the house. She was no sooner at the fountain, than she saw coming out of the wood, a lady most gloriously dressed, who came up to her, and asked a drink. This was, you must know, the fairy that appeared to her sister, but had now taken the air and dress of a princess to see how far this girl’s goodness would go. “Am I come hither”, said the proud saucy slut14 , “to serve you with water, pray? I suppose the silver tankard was bought purely for your ladyship, was it? However, you may drink out of it, if you will”. “You are not over and above mannerly”, answered the fairy, without putting herself in in a passion. “Well then, since you have so little breeding, and are so disobeying, I will give you for a gift, that at every word you speak, there shall come out of your mouth a snake or a toad”. So soon as her mamma saw her coming, she cried out, “Well daughter”. “Well mother”, answered the pert hussey15, throwing out of her mouth two vipers, and two toads. “O mercy!” cried out her mother, “What is it I see! O, it is 12 The text from the original copy is not legible A large open tub-like vessel used to carry water. It is usually made of wood hooped with iron or leather, however this particular one was made of silver. 14 A woman of dirty, slovenly, or untidy habits or appearance; a foul slattern 15 Unstandardized spelling of hussy. The term was used for a range of meanings, but in this case it would most likely mean a rustic, rude, opprobrious, or playfully rude mode of addressing a woman. 13 19 that witch16 her sister that has occasioned all this; but she shall pay for it”, and immediately she ran to beat her. The poor child fled away from her, and went to hide herself in the forest not far from thence. The king’s son, then on his return from hunting, met her, and seeing her so very pretty, asked her, what she did there alone, and why she cried? “Alas, Sir, my mamma has turned []17 out of doors. The king’s son, who saw five or six pearls, and as many diamonds come out of her mouth, desired her to tell him how that happened. She accordingly told him the whole story: and so the king’s son fell in love with her; and confiding within himself, that such a gift was more worthy than any marriage portion whatsoever in another, conducted her to the palace of the king his father, and there married her. As for her sister, she made herself so odious, that her own mother turned her off; and the miserable wretch, having wandered about a good while, without finding any body to take her in, went to a corner in a wood, and there died. 16 This word is thought to say “witch” but due to faded print in the original copy the editor is not 100% sure and has taken the liberty to make an educated guess based on context and print that can be read from the original 17 The text from the original copy is not legible 20 The Moral Money and jewels still we find; Stamp strong impressions on the mind; However, sweet discourse does yet much more; Of greater value is, and greater pow’r. Another Civil behaviour costs indeed some pains, Requires of complaisance some little share; But soon or late its due reward it gains, And meets it often when we are not aware. 21 Blue Beard There was upon a time a man who had fine houses, both in town and country, a good deal of silver and gold plate, embroidered clothes, and coaches gilded all over with gold. But this man had the misfortune to have a blue beard, which made him look so frightfully ugly, that all the women and girls ran away from him. One of his neighbours, a lady of quality, had two daughters, who were perfect beauties. He desired of her one of them in marriage; leaving her to the choice of which the two she would bestow upon him. They would neither of them have him, and sent him backwards and forwards from one another, not able to bear the thoughts of marrying a man with a blue beard. And what besides gave them disgust, and aversion, was his having been already been married to several wives, and nobody ever knew what became of them. Blue Beard, to engage their affections, took them, with the lady their mother, and three or four ladies of their acquaintance, with other young people of their neighbourhood, to one of his country seats, where they stayed a whole week. There was nothing now to be seen but parties of pleasure, hunting, fishing, dancing, mirth, and feasting. No body went to bed, but all partied the night in rallying and joking with each other: In short, everything so well succeeded, that the youngest daughter began to think that the master of the house had not a beard so very blue, and that he was a very civil gentleman. So soon as they returned home, the marriage was concluded. About a month afterwards, Blue Beard told his wife, that he was obliged to take a country journey for six weeks at least, about affairs of very great consequence, desiring her to divert herself in his absence, send for her friends and acquaintances, take them into the country, if she pleased, and make good cheer wherever she went. “Here”, said he, “are the keys of the two great wardrobes wherein I have my best furniture, these are of my silver and gold plate, which are not every day in use; these open my strong boxes, which hold my 22 money, both gold and silver; these my caskets18 of jewels; and this is the master key of all my apartments: But for this little on here, it is the key of the closet at the end of the great gallery on the first floor. Open them all; go into all and every one, except that little closet, which I forbid you, and forbid it in such a manner, that if you happen to open it, there is nothing but what you may expect from my just anger and resentment”. She promised to observe very exactly what he ordered; when he, after having embraced her, got into his coach, and proceeded on his journey. Her neighbours and friends did not stay to be sent for by the new married lady, so great was their impatience to see all the rich furniture of her house, not daring to come while her husband was there, because of his blue beard, which frightened them. They ran thro’ all the rooms, closets, and wardrobes, which were all so rich and fine, that they seemed to surpass one another. After that they went up into the two great rooms, where were the best and richest furniture they could not sufficiently admire the number and beauty of the tapestry, beds, couches, cabinets, stands, tables and lookingglasses, in which you might see yourself from head to foot; some of them were framed with glass, others with silver, plain and gilded, the finest and most magnificent that ever was seen. They ceased not to extol and envy the happiness of their friend, who in the mean time, no way diverted herself in looking upon all these rich things, because of the impatience she had to go and open the closet on the ground floor. She was so much pressed by curiosity, that, without considering it very uncivil to leave her company, she went down a back stair-case, and with such excessive haste that she had like to have broke her neck three or four times. Having come to the closet door she made a stand for some time, thinking upon her husband’s orders, and considering what unhappiness might attend her if she was disobedient; but the temptation was so strong she could not overcome it. She then took then the little key and opened it, trembling, but 18 A small box or chest for jewels, letters, or other things of value. The casket itself is normally very valuable and richly ornamented. 23 she at first could not see any thing plain, because the windows were shut. After some time she began to perceive that the floor was covered with clotted blood, on which lay the bodies of several dead women ranged against the walls; (these were all the wives of Blue Beard had married and murdered one after another), she thought she should have died with fear, and the key that she pulled out of the lock, fell out of her hand. After having somewhat recovered her surprise, she took up the key, locked the door, and went up stairs into her chamber to recover herself; but she could not, so much was she frightened. Having observed that the key of the closet was stained with blood she tried two or three times to wipe it off, but the blood would not come out; in vain did she wash it, and even rub it with soap and sand, the blood still remained, for the key was a fairy19, and she could never make it quite clean; when the blood was off of one side, it would come on the other. Blue Beard returned from his journey the same evening, and said he had received letters upon the road, informing him the affair he went about, was ended to his advantage. His wife did all she could to convince him she was extremely glad of his speedy return. Next morning he asked her for the keys, which she gave him, but with such a trembling hand that he easily guessed what had happened. “What”, said he, “is not the key of my closet among the rest?” “I must certainly”, answered she, “have left it upon the table.” “Fail not”, said Blue Beard, “to bring it to me presently”. After several goings backwards and forwards, she was forced to bring him the key. Blue Beard having very attentively considered it, said to his wife, “how comes this blood upon the key?” “I do not know”, cried the poor woman, paler than death. “You do not know”, replied Blue Beard, “I very well know, you were resolved to go into the closet, were you not? Very well, madam; you shall go in and take your place among the ladies you saw there”. 19 Enchantment, magic; a magic contrivance; an illusion, a dream 24 Upon this she threw herself at her husband’s feet, and begged his pardon with all the signs of a true repentance, and promised that she would never more be disobedient; she would have melted a rock, so beautiful and sorrowful is she. Blue Beard had a heart harder than any rock. “You must die, madam, and that presently” “Since I must die”, answered she, looking upon him with her eyes all bathed in tears, “give me some little time to say my prayers” “I give you”, replied Blue Beard, “a quarter of an hour, but not one moment more”. When she was alone, she called out to her sister, and said to her, “Sister Anne”, for that was her name, “go up, I beg you, upon the top of the tower, and look if my brothers are not coming they promised that they would come to day, and if you see them, give them a sign to make haste”. Her sister Anne went up to the top of the tower, and the poor afflicted wife cried out from time to time, “Anne, sister Anne, do you see any one coming?” And sister Anne said, “I see nothing but the sun which makes a dust, and the grass which looks green”. In the mean time, Blue Beard, holding a great cutlass in his hand, cried out as loud as he could bawl, “Come down instantly, or I will come up to you” “One moment longer if you please”, said his wife; and then she cried out very softly, “Anne, sister Anne, do you see any body coming?” And sister Anne said, “I see nothing but the sun which makes a dust, and the grass that grows green” “Come down quickly”, cried Blue Beard, “or I will come up to you” “I am coming”, answered his wife; and then she cried, “Anne, sister Anne, dost thou see any body coming?” “I see”, replied sister Anne, “a great dust coming on this side” “Are they my brothers?” “Alas! no dear sister, I see a flock of sheep” “Will you not come down?”, cried Blue Beard. “One moment longer”, said his wife, and then she cried out, “Anne, sister Anne, dost thou see no body a coming?” “I see”, says Anne, “two horsemen coming, but they are yet a good way off” “God be praised”, replied the poor wife joyfully, “they are our brothers” “I am 25 making them a sign, as well as I can, to make haste”. The Blue Beard bawled out so loud that he made the whole house tremble. The distressed wife came down, and threw herself at his feet all in tears, with her hair about her shoulders: “This signifies nothing”, said Blue Beard, “you must die”; then taking hold of her hair with one hand, and lifting up his cutlass with the other, he was going to cut off her head. The poor lady turned about to him, and looking at him to afford her time to recollect herself. “No, no”, said he, “recommended thyself to God, and was just going to strike”. At this very instant there was such a loud knocking at the gate, that Blue Beard ,made a sudden stop. The gate was opened, and presently entered two horsemen, who drawing their swords, ran directly to Blue Beard. He knew them to be his wife’s brothers, one a dragoon, the other a musqueteer: so that he ran away immediately to save himself; but the two brothers followed so close, that they overtook him before he got to the steps of the porch, where they ran their swords thro’ his body, and left him dead. The poor wife was almost as dead as her husband, and had not strength enough to arise and welcome her brothers. Blue Beard had no heirs, and so his wife became mistress of all his estate. She made use of one part of it to marry her sister Anne to a young gentleman, who had loved her a long time, another part to buy colonels commissions for her brothers; and the rest to marry herself to a very worthy gentleman, who made her forget the ill time she had passed with Blue Beard. The curiosity of Blue Beard’s wife had well night cost her her head; and this disposition will bring all of all sexes, who indulge it beyond the bounds of prudence, into difficulties they can hardly escape from. Yet the reader is desired to take notice that there are two species of this turn or mind: the one commendable, when it leads to knowledge, the other blameable, when it only serves to gratify an idle inquisitiveness. 26 The Moral Curiosity! thou mortal baue, Spire of thy charms, thou caused often pain, And sore regret, of which we daily find A thousand instances of mankind: For thou, O may it not displease the fair, A fleeting pleasure art, but lasting care; And always []20, alas! too dear the prize, Which in the moment of possession dies. Another. A very little [ ]21 of common sense, And knowledge of the world will soon convince, That this story is of some long past, No husband now such panic terror cast; Nor weakly with a vain despotic hand, Imperious, what’s impossible command; And be they discontinued, or the fire 20 21 The text from the original copy is not legible The text from the original copy is not legible 27 Of wicked jealously their hearts inspire, They softly sing; and of whatever hue Their beards may chance to be, or black or blue, Grizzled, or [ ]22, it is hard to say, Which of the two , the man or wife, [ ]23. 22 The text from the original copy is not legible The text from the original copy is not legible. You can make out “be__sway” but the middle letter(s) cannot be read and there is no guess for the word. 23 28