- Institute of Technology Sligo

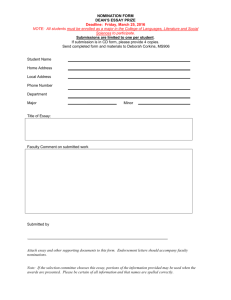

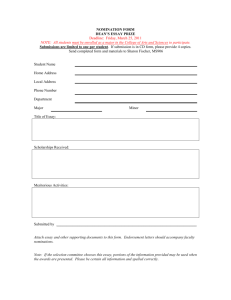

advertisement