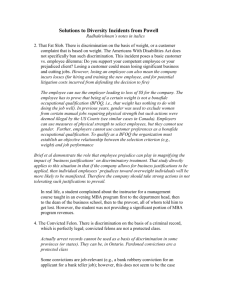

Bona Fide Occupational Requirement

advertisement